Japan’s plan to release treated radioactive water into the ocean is safe and there is no better option to deal with the massive buildup of wastewater collected since the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster, the head of the United Nations’ nuclear watchdog told CNN.

Japan will release the wastewater sometime this summer, a controversial move 12 years after the Fukushima nuclear plant meltdown. Japanese authorities and the IAEA have insisted the plan follows international safety standards – the water will first be treated to remove the most harmful pollutants, and be released gradually over many years in highly diluted quantities.

But public anxiety remains high, including in nearby countries like South Korea, China and the Pacific Islands, which have voiced concern about potential harm to the environment or people’s health. On Friday, Chinese customs officials announced they would maintain a ban on food imports from 10 Japanese prefectures including Fukushima, and strengthen inspections to monitor for “radioactive substances, to ensure the safety of Japanese food imports to China.”

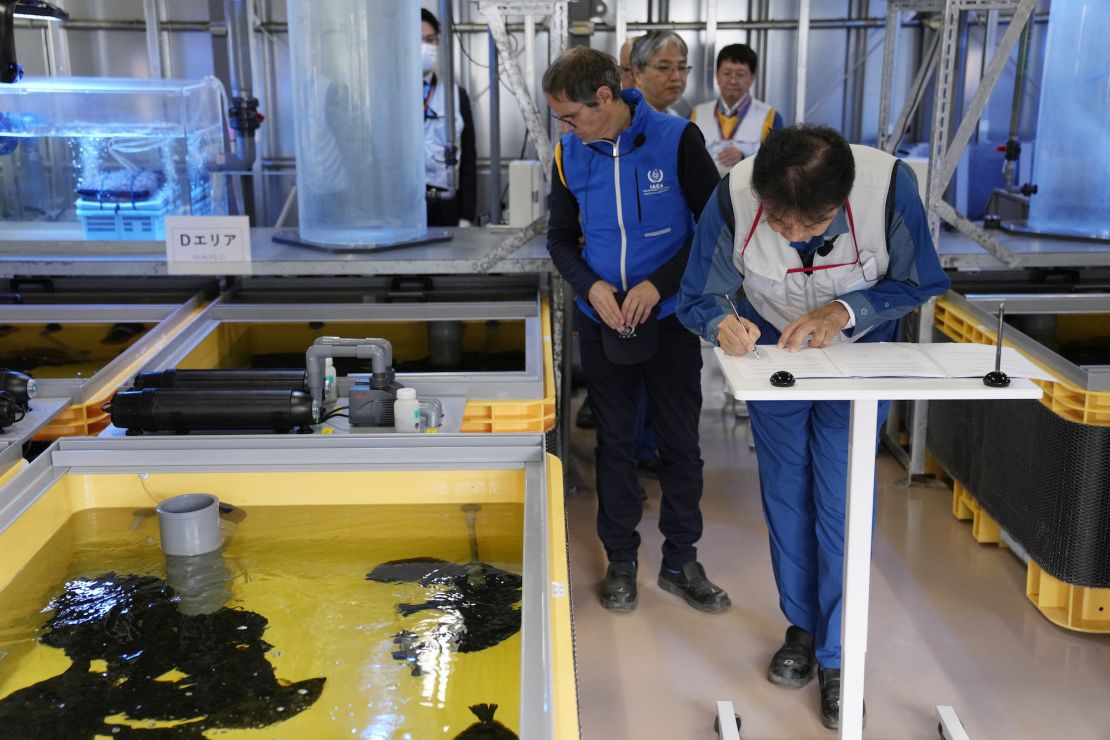

Speaking in an interview during a visit to Tokyo Friday, International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) Director General Rafael Grossi said that while fears over the plan reflect a “very logical sense of uncertainty” that must be taken seriously, he is “completely convinced of the sound basis of our conclusions.”

“We have been looking at this basic policy for more than two years. We have been assessing it against … the most stringent standards that exist,” he said. “And we are quite certain of what we are saying, and the scheme we have proposed.”

Grossi told CNN he had met with Japanese fishing groups, local mayors and other communities affected by the 2011 disaster – and whose livelihoods may be hurt by the release – to listen to those concerns.

“My disposition … is one of listening, and explaining in a way that addresses all these concerns they have,” he said.

“When one visits Fukushima, it is quite impressive, I will even say ominous, to look at all these tanks, more than a million tons of water that contains radionuclides – imagining that this is going to be discharged into the ocean. So all sorts of fears kick in, and one has to take them seriously, to address and to explain.

“This is why I’m here, to listen to all those who in good faith have questions and criticism and question marks, and to address them.”

On Tuesday, Grossi formally presented the IAEA’s safety review to Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida. The report found the wastewater release plan will have a “negligible” impact on people and the environment, adding that it was an “independent and transparent review,” not a recommendation or endorsement.

‘No’ better alternatives

Japanese authorities have said the release is necessary because they are running out of room to contain the contaminated water – and the move will allow the full decommissioning of the Fukushima plant.

The 2011 disaster caused the plant’s reactor cores to overheat and contaminate water within the facility with highly radioactive material. Since then, new water has been pumped in to cool fuel debris in the reactors. At the same time, ground and rainwater have leaked in, creating more radioactive wastewater that now needs to be stored and treated.

That wastewater now measures 1.32 million metric tons – enough to fill more than 500 Olympic-sized swimming pools.

Japan has previously said there were “no other options” as space runs out – a sentiment Grossi echoed on Friday. When asked whether there were better alternatives to dispose of the wastewater, the IAEA chief answered succinctly: “No.”

It’s not that there are no other methods, he added – Japan had considered five total options, including hydrogen release, underground burial and vapor release, which would have seen wastewater boiled and released into the atmosphere.

But several of these options are “considered industrially immature,” said Grossi. For instance, vapor release can be more difficult to control due to environmental factors like wind and rain, which could bring the waste back to earth, he said. That left a controlled release of water into the sea – which, Japanese officials and some scientists point out, is frequently done at nuclear plants around the world, including those in the United States.

The IAEA will also remain on site for years to come, with a new permanent office set up in Fukushima to help monitor progress.

“We have the benefit of science,” Grossi said. “Either you have a certain radionuclide in a water sample or you don’t have it … it’s a measurable thing. We have the science, we have the laboratories … to ensure the credibility and the transparency of the process.”

International skepticism

But some critics have cast doubt on the IAEA’s findings, with China recently arguing that the group’s assessment “is not proof of the legality and legitimacy” of the wastewater release.

Many countries have openly opposed the plan; Chinese officials have warned that it could cause “unpredictable harm,” and accused Japan of treating the ocean as a “sewer.” The Secretary General of the Pacific Islands Forum, an inter-governmental group of Pacific island nations that includes Australia and New Zealand, also published an op-ed in January voicing “grave concerns,” saying more data was needed.

And in South Korea, residents have taken to the streets to protest the plan. Many shoppers have stockpiled salt and seafood for fear these products will be contaminated once the wastewater is released – even though Seoul has already banned imports of seafood and food items from the Fukushima region.

International scientists have also expressed concern to CNN that there is insufficient evidence of long-term safety, arguing that the release could cause tritium – a radioactive hydrogen isotope that cannot be removed from the wastewater – to gradually build up in marine ecosystems and food chains, a process called bioaccumulation.

While Grossi said he takes these objections seriously, he added that he “cannot exclude” the possibility some are driven more by politics than science.

“We understand that there is a political environment … which is tense. Geopolitical divisions are very, very strong these days so we cannot exclude these things,” he said.

Grossi also denied media reports that the IAEA had shared a draft of its final report with the Japanese government ahead of its publication. “It’s absurd,” he said. “This is the DNA of the IAEA – to be the nuclear watchdog for nuclear operations, the nuclear watchdog for nuclear safety and security. When we come to a conclusion, it is our independent conclusion.”

And more broadly, the future of nuclear as an alternative energy source relies on the success of the Fukushima release, he said. Though there has been heightened public alarm toward nuclear plants recently – for instance, regarding the Russian-occupied Zaporizhzhia plant in Ukraine – “the problem there is war, the problem is not nuclear energy,” Grossi said.

“If there was one lesson that came clearly after the Fukushima accident, it’s that the nuclear safety standards should be observed to the letter,” he added. “If you do that, the probability of having what happened in Fukushima is extremely low.”

Correction: This story has been updated to reflect the status of China's food import bans on Japan.