The Republican response to Donald Trump’s latest criminal indictment offers a clear test of the famous saying that the definition of insanity is doing the same thing over again and hoping for a different result.

The choice by Republican leaders, and even almost all of his 2024 rivals for the Republican presidential nomination, to unreservedly defend Trump after he was indicted earlier this year by the Manhattan district attorney helped the former president to widen his lead in primary polls. The roar of outrage from Republican leaders to that indictment restored Trump’s grip on the party after frustration over his role in the GOP’s disappointing 2022 midterm elections had loosened it.

But since last week’s disclosure that Trump faces another criminal indictment – this one federal, over his handling of highly classified documents – the party leadership and 2024 field has almost entirely replicated that deferential approach.

Repeating the pattern from other moments of maximum threat to Trump, the GOP response has been marked by a pronounced communications imbalance. From House Speaker Kevin McCarthy to South Carolina Sen. Lindsey Graham, Trump’s supporters have loudly supported his claims that he is being persecuted by the left.

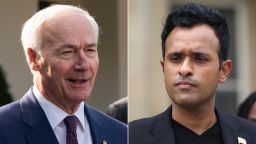

Simultaneously, with only a few conspicuous exceptions like second-tier presidential contenders Chris Christie and Asa Hutchinson, the most Trump’s critics in the party have been willing to do is remain silent and not validate his vitriolic charges. Apart from those two former governors, just a short list of prominent Republicans – including former Trump administration senior officials William Barr and John Bolton, and Senate Minority Whip John Thune – have pushed back at all against Trump’s claim that he is being hunted by “lunatic,” “deranged” and “Marxist” prosecutors, or publicly expressed misgivings about the underlying behavior detailed in the federal indictment against him.

By refusing to confront Trump or his enraged defenders more directly, the Republicans who want the party to move beyond him in 2024 may be stitching their own straitjacket. The nearly indivisible GOP defense of Trump has once again created a situation in which a controversy that is weakening Trump with the broader electorate is strengthening his position inside the GOP coalition.

Perhaps not surprisingly, multiple public polls show that most voters outside the Republican base are worried Trump jeopardized national security and dubious that anyone convicted of a serious crime should serve again as president. In a NPR/PBS NewsHour/Marist poll this spring, roughly three-fourths of independents, people of color, and voters under 45, as well as four-fifths of college-educated Whites, said they did not want Trump to be president again if he’s convicted of any crime. (The poll was conducted after Trump’s indictment in Manhattan but before the recent federal charges.)

In a CBS News/YouGov poll conducted partially after last week’s indictment, a solid 57% majority of Americans – including around three-fifths of college-educated Whites and voters under 30 and nearly that many independents – said he should not serve as president if he’s convicted specifically in the classified documents case. More than two-thirds of Americans overall said his handling of classified documents had created a national security risk.

Yet those same surveys also show that the vast majority of Republican voters say they do not believe Trump’s behavior is disqualifying – even if he’s convicted – and accept his claim that he’s the victim of unfair treatment. (In the Marist survey, more than three-fifths of Republicans said they would welcome a second Trump term even if he is found guilty of a crime.) That, too, may be unsurprising given the paucity of conservative elected officials or media figures that those voters trust telling them otherwise.

Historian Ruth Ben-Ghiat, who studies authoritarian leaders, sees more than tactical political maneuvering in the choice by so many Republicans to again immediately lock arms around Trump despite the powerful evidence detailed in last week’s indictment. Such deference is “completely consistent” with the behavior across the world of “autocratic parties” under the thrall of “a leader cult,” says Ben-Ghiat, author of the 2020 book, “Strongmen: Mussolini to the Present.”

The closest recent parallel she sees to the GOP’s behavior might be how the Forza Italia party remained in lockstep for years behind former Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi throughout multiple trials (and even convictions) for corruption and sexual misconduct, amplifying his claims that he was the victim of a vast conspiracy and “witch hunt.” For leaders like Trump or Berlusconi (who died at 86 on Monday) such legal challenges, she says, actually become a “juncture” to strengthen their dominance by demanding that others publicly defend their behavior – no matter how indefensible. In that way, the leader establishes personal loyalty to him as the one true litmus test for belonging to the party. (The Republican decision to replace a party platform in 2020 with a brief statement declaring it would “enthusiastically support” Trump’s agenda, she notes, marked an important milestone in that transition.)

“If you stay in the party it’s either you have to be supporting Trump or face the consequences,” says Ben-Ghiat, who teaches at New York University. “You could be even running against him, but you have to adhere to the party line: the weaponization by the deep state. That’s the sad and dangerous part among many dangers we face. Even those people are stuck within this narrative world and this party line and their targets are the same as Trump’s.”

Trump’s latest round of legal jeopardy leaves the Republicans who are hesitant about him – either because they consider him unfit to serve as president or simply because they believe he is too damaged to win a general election – in the same position as his critics since 2015: hoping that his supporters will somehow move away from him, but unwilling to do almost anything overt to encourage them.

“They keep indulging the fantasy. … They don’t ever have to do anything and a deus ex machina is going to do this by itself,” says long-time conservative strategist Bill Kristol, who has emerged as one of Trump’s most dogged GOP critics.

Some Republicans say it’s possible this time will be different and the sheer weight of legal proceedings mounting against Trump – which could include further charges over his role in trying to overturn the 2020 election from special counsel Jack Smith and Fulton County, Georgia, District Attorney Fani Willis – could cause what some call “indictment fatigue” among GOP voters.

“I think there’s a schizophrenia that exists in this,” says Dave Wilson, a prominent social conservative and Republican activist in South Carolina. “You have people who say that no government should be used to weaponize against any one of us, much less a [former] president. At the same they are beleaguered about the same headlines again and again and again about indictments.”

Likewise, Craig Robinson, former political director for the Iowa Republican Party, agrees that given the prospect of cascading court appearances through the election year, “Donald Trump is asking a lot of the Republican voter to endure.”

But many other Trump critics inside the GOP fear that the chorus of support for him from party leaders and his 2024 rivals has set in motion a dynamic where denying him the nomination now could appear to some GOP voters as “rewarding” the Democrats, or the “deep state,” or President Joe Biden, or whoever they believe is persecuting him. “He will win the nomination with the message that they have weaponized the justice system against Republicans, against conservatives,” predicts former New Hampshire GOP chairperson Jennifer Horn, now a staunch Trump critic.

Trump has quickly made clear that he will stress that argument against any and all criminal claims converging against him. When he appeared for the first time after this latest indictment, at the Georgia GOP convention on Saturday, he argued that the “deep state” was targeting him because it recognized that he was the only 2024 candidate strong enough to stand up to it on behalf of Republican voters. “Our enemies are desperate to stop us because they know that we, we, are the only ones who are going to be able to stop them,” he declared. At another point Trump insisted, “These criminals cannot be rewarded” – presumably by frightening Republican voters away from nominating him.

Such arguments from Trump show how his 2024 rivals, by mostly endorsing his claims, have voluntarily reduced themselves to the chorus in his drama. So long as the dominant story in red America is the claim that Democrats are unfairly targeting Trump, it may be difficult for the other candidates even to sustain attention in the Republican race.

“They’ve made themselves just sub-characters in the plot,” says Horn. “Every time they do this they make him the hero. So they are out there asking people to vote for them for president, even though they are saying Donald Trump is the real hero in this scenario. It doesn’t make any sense.”

Robinson largely agrees. Trump’s multiple indictments, he says, “might be a good opportunity for” for the former president’s 2024 rivals because some voters, even if they consider the allegations unfair, will “also think ‘I don’t want the next 12-18 months to be’” dominated by those controversies. Yet, Robinson believes, by echoing Trump’s claims of unfair treatment, the other candidates are encouraging Republican voters to accept his framing of the race. “If you believe the whole thing is corrupt and needs to be torn down and rebuilt, isn’t he the best one to do that?” says Robinson, adding that among many GOP voters, “There’s this sense that he’s the only one who can fight that fight.”

Kristol points out that other Republicans with a plausible chance of winning the nomination could distance themselves from Trump without fully endorsing the charges against him. “They can’t sound like me, they can’t sound like Asa Hutchison,” Kristol acknowledges. But he adds, other Republican candidates could respond to this indictment (and any potential subsequent ones) by expressing faith in the legal system to find the truth and saying something like: “‘I think Donald Trump did a good job, but this is bad, and when you can combine this with the ’22 results, we need a different nominee.” It’s an ominous measure of the party’s transformation into Trump’s personal vehicle, Kristol says, that they feel they “can’t even do that and instead want to attack Biden.”

It remains possible that Trump’s rivals or other GOP leaders could make a more explicit case against him as the race proceeds, or more possible indictments land. Comments on Monday from Thune and presidential contender Nikki Haley – who criticized Trump’s handling of the documents after initially attacking the indictment – suggest a window may be cracking open for greater GOP dissent. But the hesitation inside the party about fully confronting Trump remains palpable. At his campaign announcement last week, for instance, former Vice President Mike Pence said more explicitly than ever before that Trump’s behavior on January 6, 2021, rendered him unfit to serve as president again. But Pence immediately undercut that message by declaring in a CNN town hall later that day that he would “support the Republican nominee in 2024,” which very well could be Trump, even though Pence said he doubted it would be. What started as a challenge to him instead became another measure of Trump’s dominance – a shift underscored when Pence joined the chorus condemning the federal indictment.

Because Ben-Ghiat sees the GOP taking on more of the characteristics of other “authoritarian parties” in thrall to strongman leaders, she’s skeptical the legal challenges converging around Trump will undermine his hold on the party. But, she says, the experience of other countries shows that imposing legal consequences for the misdeeds of authoritarian-minded leaders is nonetheless critical to fortifying democracy.

There may be no proof of wrongdoing that can move large numbers of voters in Trump’s coalition, she says, but for everyone else in society, “it is very important to show that the rule of law can hold, that our institutions can do things, that democracy can work.”

Ben-Ghiat likens the multiple legal proceedings around Trump to the “truth commissions” established in countries such as South Africa and Chile that cataloged and documented the misdeeds of autocratic governments. “In the short run,” she says, the threat to US democracy “may get worse before it gets better” as Trump, echoed by most of the GOP leadership and conservative media, portrays any accountability for him as a conspiracy against his followers.

“But in the long run,” she says, establishing the evidence of any misconduct or criminal behavior through indictments, testimony and trials “that everyone can read is very, very important.” For anyone concerned about upholding the rule of law, Ben-Ghiat says, the choice by so many Republican leaders to preemptively dismiss any allegation against Trump “is just more proof of how important these procedures are.”