Editor’s Note: This article was originally published by The Art Newspaper, an editorial partner of CNN Style.

Françoise Gilot, a tireless artist who defied simple categorization — and efforts to define her merely as a footnote in the story of her former lover Pablo Picasso — died Tuesday in New York. She was 101.

Her death was confirmed to The New York Times by her daughter, Aurelia Engel, who said Gilot had recently suffered from lung and heart problems. CNN was unable to reach Engel, or Gilot’s other children, to confirm these details.

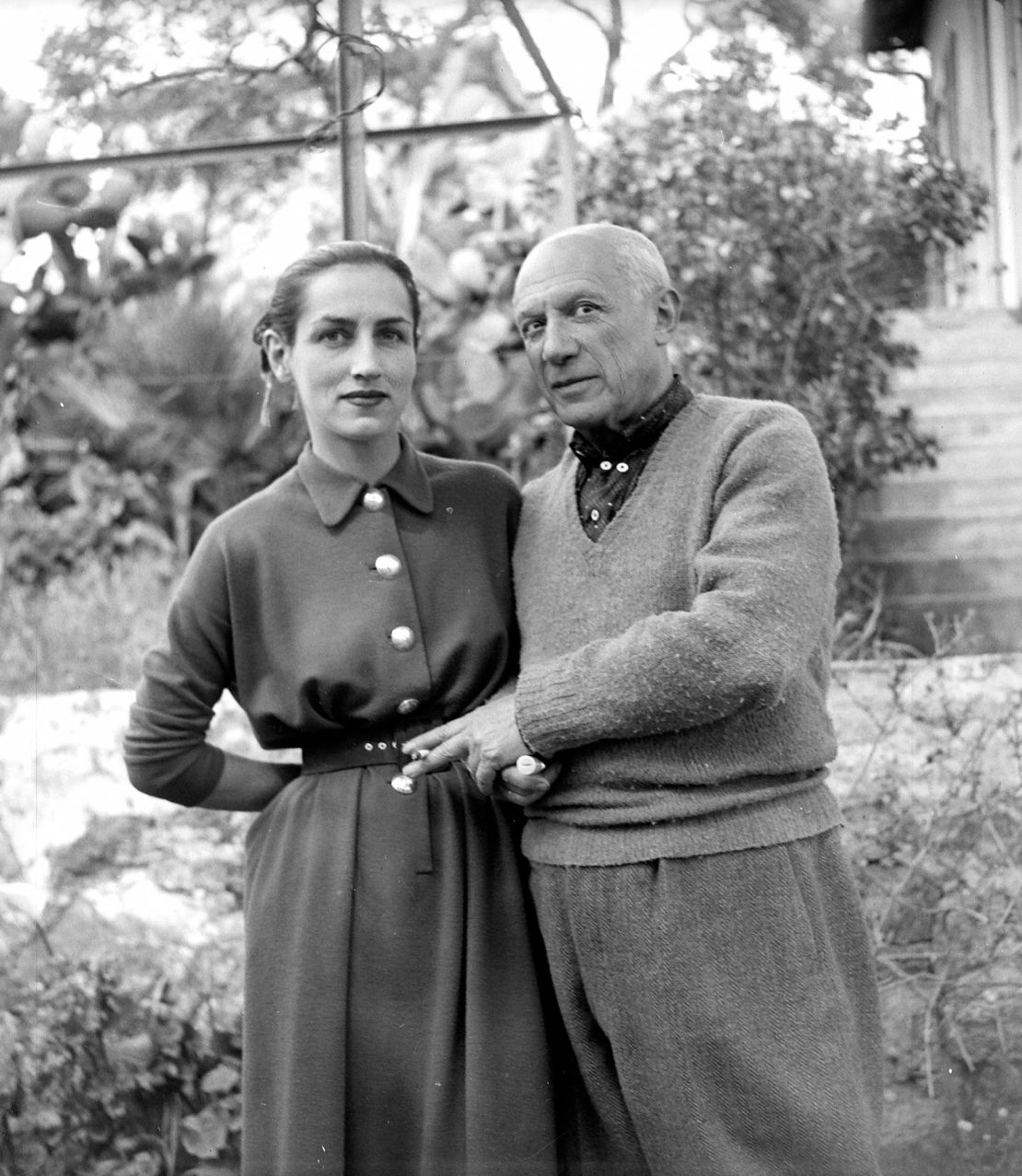

Gilot, whose output spanned more than 80 years, was born in the Paris suburb of Neuilly-sur-Seine on November 26, 1921, and studied philosophy and law before devoting herself fully to being an artist. The early years of her career coincided with World War II and the Nazi occupation of Paris. During that time she had her first exhibition, at dealer Madeleine Decre’s eighth arrondissement gallery in 1943, and met Picasso, who was 40 years her senior. Her assessment of their ensuing 10-year relationship, published in a 1964 memoir written with journalist Carlton Lake titled “Life with Picasso,” earned Gilot the ire of Picasso’s supporters and, eventually, made her a heroic figure in feminist art history.

“Sometimes people like you. Sometimes people don’t,” Gilot said in a 2019 interview with The New York Times’ T Magazine. “But you are not going to fashion yourself according to other people’s wishes, whether they are negative or positive, you know? You have to be true to yourself and true to the truth. That’s the only two things that are important. I don’t think I have to be true to what the public in general thinks, because, then, why should I say something they already have made up their mind about?”

By the mid-1950s, Gilot’s relationship with Picasso had ended — they had two children together, Claude and Paloma Picasso — and she had married artist Luc Simon. A few years later, she began showing with Paris’ Galerie Louise Leiris and her work continued to evolve from the Cubist mode she explored in the early 1950s to a flattened figurative style characterized by strong geometry and bright colors.

The following decade, despite the uproar caused by her memoir, Gilot exhibited extensively in Europe and the United States — including New York’s David Findley Gallery, Galleria Santo Stefano in Venice, Galleria Dantesca in Turin and Galerie Coard in Paris. In 1962, she and Simon (Engel’s father) divorced.

In 1970, Gilot married her second husband, Jonas Salk, a virologist who developed one of the first polio vaccines. That same year, she had her first solo museum exhibitions, though many more would follow in the next few years. In addition to painting, Gilot continued to pursue printmaking and poetry. She published her first artist book of prints and poems, “Sur la Pierre (On the Stone),” in 1972 with Parisian print studio Mourlot Atelier. By the middle of the decade, Gilot’s primary residence with Salk was near San Diego, California, though she spent a great deal of her time traveling for exhibitions and other projects.

In a statement, Gerald Joyce, the president of the California-based Salk Institute — a scientific foundation established by Jonas Salk — said: “Françoise Gilot has been truly inspirational to all of us at Salk, to Jonas during his life and to our entire community through her involvement with Symphony at Salk and many other Salk undertakings. Her artistic genius can be seen on display around campus through the many pieces of art she donated to us. While we grieve her death, we celebrate Françoise’s spirit as we reflect on her art and her commitment to the Salk Institute.”

Gilot had been based in New York since the early 1980s, while a prodigious cadence of exhibitions kept her traveling through the US and Europe. In 1998, an exhibition at New York’s Elkon Gallery shined a light on her works from the 1940s. In 2000, Acatos Publishing released a monograph chronicling her work all the way back to 1940. While her earlier work had remained rooted in figuration — whether stylized and streamlined or deconstructed in a Cubist vein — in the latter decades of Gilot’s career her paintings became increasingly abstract, defined by organic forms rendered in vibrant colors.

In 2012, Gagosian staged the first exhibition of Gilot’s work alongside Picasso’s, “Picasso and Françoise Gilot: Paris–Vallauris 1943–1953,” which focused on works made during their relationship. The exhibition was developed in part through a collaboration between Gilot and Picasso biographer John Richardson, a seemingly improbable partnership given that Richardson had panned her memoir in a 1964 review for the New York Review of Books.

“He had never met me, and then he judged me according to things he had heard,” Gilot had said of her friendship with Richardson, who had died a few months earlier, in the 2019 T Magazine interview. “Then, when he met me, we became very good friends. What can I say? Many people thought that by being against me, they would be pleasing to Picasso. That’s why they did it.”

Gilot’s work is in the permanent collections of the Musée Picasso in Antibes, the Museum of Modern Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Musée d’art moderne de la ville de Paris, the New Orleans Museum of Art and the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, DC, among others.

Despite spending most of the second half of her life in the US, Gilot was repeatedly awarded national honors in France. In 1978, she was made an officer of the Order of Arts and Letters by France’s culture minister. In 1994, French president Jacques Chirac would make her an officer of the Order of National Merit. And in 2009, president Nicolas Sarkozy made her an officer of the Legion of Honor, France’s highest order of merit.

“What I really learned in that first phase (of my career): never again belong to a group, because in a group some people are always the leaders and they always want the others to conform, and I am a non-conformist,” Gilot told WHYY’s Terry Gross in an interview in 1988, on the occasion of the release of her book “An Artist’s Journey.”

“I want to conform only to my own self and the deep desires that motivate me as an artist, and I couldn’t care less about whether the others are going that route or not. Ultimately, if I have lived my life as an artist right, my work — which I call ‘the artist’s journey,’ which is a kind of pilgrimage toward my own center, my own being — that’s the only thing that is important. And after all, I have enough of a following as it is, so I think I did the right thing.”