President Joe Biden sat behind the Resolute Desk in his first evening Oval Office address with a clear purpose: to deliver the final word.

A bipartisan bill to avert the crisis that loomed over Washington for most of the year so far was in hand. And the moment offered Biden an opportunity to reflect what he views as the inextricable connection between the deal, the case for his presidency he made to voters more than two years prior and the one he will count on to secure him another four years in 17 months and two days.

“I know bipartisanship is hard and unity is hard, but we can never stop trying, because at moments like this one, the ones we just faced where the American economy and the world economy is at risk of collapsing, there is no other way,” Biden said Friday.

It was also a chance to bust out of the seams of the close-to-the-vest messaging strategy that he and the three senior members of his team maintained during the three weeks of painstaking negotiations.

Even as House Speaker Kevin McCarthy and his top two negotiators maintained a steady drumbeat of public statements and strategic messaging, the White House kept their powder dry. Even as Democrats simmered, and at some points outright boiled over with frustration as slivers of potential agreements reached public view, Biden held back.

For Biden’s top three negotiators, counselor Steve Ricchetti, Legislative Affairs Director Louisa Terrell and Budget Director Shalanda Young, the public reticence sat in sharp contrast to a behind the scenes operation in which Biden was constantly briefed and sought details on even the smallest elements of proposed appropriations adjustments designed to backstop spending cuts.

The posture, his advisers said, was intentional. As divided government steadily moved toward the precipice of calamity, Biden didn’t want to unsettle the ongoing, and exceedingly fluid, closed-door talks.

But Biden, as he commended McCarthy’s efforts, also alluded to a clear reality that hung over talks where an outcome was viewed as the only option – but at times seemed impossible to achieve.

“The stakes could not have been higher,” Biden said.

‘What are they gonna say, no to veterans?’

By the time McCarthy walked into the Oval Office for his first meeting with the president and congressional leaders on May 9, the White House had spent the previous two weeks accusing House Republicans of seeking to cut veterans’ benefits as part of their legislation to raise the debt ceiling, which slashed non-defense spending across the board.

It was a deliberate and carefully planned political attack designed to have maximum effect. No, the House Republican legislation did not specify cuts, officials privately acknowledged. But the ambiguity tied to the deep topline cut also meant they didn’t specify those benefits would be protected.

On that basis, the attack became the cornerstone element of every public statement from Biden down on the debt limit.

It was one the president deployed once again behind closed doors at the White House.

Pressing McCarthy for specifics on which parts of the budget he was willing to cut to achieve his target, Democrats in the room went down a list of big-ticket items: Public safety? No. FBI? No. Border security? No.

At the mention of veterans’ funding, McCarthy grew animated, pointedly telling Biden that the notion he was seeking to cut such funding was a lie.

At the time, that moment laid bare weighty tensions between two sides staring down the prospect of default in under a month. In retrospect, it was a pivotal moment that helped the White House pave the way for the key mechanisms of a deal that leans on veterans’ carveouts to blunt spending cuts to domestic programs and changes to a key food assistance program.

With Memorial Day on the horizon, senior White House officials said protecting veterans’ benefits was a top priority. They also knew it was a sensitive issue for Republicans’ politically, especially as House Republicans parried White House allegations about cuts to veterans’ services.

“It was very much a through line that we identified and worked through in different points in the process,” Terrell said. “We were willing and able to be quite pointed.”

That strategy propelled negotiators to agree early in the talks to exempt veterans benefits from caps on discretionary domestic spending, effectively shrinking the size of cuts the White House would need to backstop with Internal Revenue Service and Covid relief funds.

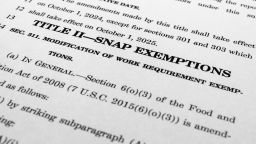

The White House would use the same key to unlock one of the thorniest sticking points of the final stretch of negotiations as Republicans pushed to expand work requirements for food stamp recipients.

“You don’t mean to tell us that we’re going to hurt, you know, homeless veterans here right?” White House negotiators told their Republican counterparts, according to a senior administration official.

“No, no, no,” came the response.

“Well then we should exempt that,” the negotiators retorted.

“What are they gonna say, no to veterans?” Young said recalling the interaction.

Republicans would later agree to exempt veterans, as well as the homeless and individuals who had been through the foster care system, from SNAP work requirements, delivering a surprise net result for the White House: more – not fewer – individuals will gain access to food stamps, according to the Congressional Budget Office.

Republicans disputed the CBO’s analysis outright. Progressive Democrats, unsettled by what in their view was weeks of being boxed out of the negotiations, still sharply objected to the inclusion of the issue altogether.

But the outcome clinched agreement on a central redline issue for McCarthy. White House officials, over the course of the painstaking negotiations, viewed the issue as largely a wash – and one that brought them to the brink of a final agreement.

“If we had said that was possible, you would have said, ‘How is that going to happen?’” White House chief of staff Jeff Zients said in an interview.

“If 3, 4, 5 weeks ago, I had told you that we were going to have something that passed the House with 314 votes, 165 Democrats – I think we both would’ve said that’s not possible, or that is a pipe dream,” Zients said, touting the success of the White House’s strategy. “And that’s what happened.”

A key weekend hurdle

It was a perspective echoed by people involved in the process from both sides of the negotiation. To some degree, the scale of the bipartisan support served to obscure what had, at various points, seemed on the verge of falling apart entirely.

“There probably were a few moments where it seemed like it was going to be hard to think through how we were going to be able to resolve our differences. I’m sure they felt it as well,” Ricchetti said.

None more so than the weekend that began with Republicans hitting a public “pause” on negotiations.

“We had probably three major blowups in this negotiation, one of which was that Friday,” said Rep. Patrick McHenry, one of the lead Republican negotiators, of May 19.

Republicans had started from the position that budget caps would need to extend for a 10 year period. As negotiators pressed forward, they would come down to six years, but remained firmly in that spot, determined to secure at least $2 trillion in cuts.

The White House, citing precedent, was open to two.

Finding the pathway to reconcile those deeply divergent positions was tailor-made for Young.

As the former staff director of the House Appropriations Committee, Young brought to the talks a combination of institutional knowledge, deeply ingrained understanding of years of spending warfare and deals, and innate sense of how to read the other side in heated negotiations, White House officials involved in the process said.

Within days of her first forray into the negotiations – as the scale of the gulf between the two sides on the budget side of the negotiations was laid bare – Young returned home one night and could hardly close her eyes at all, consumed by the need to find the combination of timeline, topline and extra money back fill in order to secure a compromise that could bridge the two sides.

That night, punctuated by late night and early morning messages to her ever-present deputy Michael Linden, would mark the start of piecing together an agreement that would lock in a two year caps agreement, with an additional four years that had no enforcement mechanism.

The long-standing baseline of parity between defense and non-defense dollars would be broken – an outcome Republicans pointed to as a clear win – but the length of the agreement and depth of the cuts moved sharply back toward a point White House officials deemed acceptable.

Still, the ability to clearly advance toward an agreement remained out of reach.

White House officials would engage in conversations where their Republican counterparts would outline a potential resolution on issues. But the specific details remained outside the talks. It was a reality that drew a wary response from the White House team, which was keenly aware that reluctance to put anything on paper was likely tied to concerns about leaks that would blow up any deal.

If just the threat of widespread House GOP rejection was enough to slow progress, how could any be made at all?

“We were just like, show us the paper,” Terrell said, recalling Young’s constant refrain as officials attempted to nail down exactly what Republicans were willing to put on the table.

Negotiations resumed later that night, but progress was halting over the weekend, with one senior administration official describing the situation as “stalemated.” It wasn’t until Ricchetti spoke with McCarthy, followed by a call from the president that the negotiations appeared to get back on the right trajectory.

“The president’s conversation with the speaker freed up the end stage of that negotiation and enabled us to finish,” Ricchetti told CNN.

The White House’s readout of that call was bare bones – noting only that they spoke by phone and that their staffs would reconvene that evening. That was by design: after hanging up with McCarthy, Biden directed his team to release as little information as possible about the call, in order to give the negotiations more space.

A shift in tone and negotiators

McCarthy’s second appearance in the Oval Office last month cemented the view among the president’s negotiators that they were sitting across the table from people negotiating in good-faith.

Multiple senior administration officials said McCarthy’s demeanor in the second Oval Office meeting had changed and he was demonstrating that he “wanted a deal.”

The shift in tone was paired that day with another critical development: a shift in the makeup of the players at the table.

For months, White House officials hoped – and to some degree based on past battles, expected – Senate Republican Leader Mitch McConnell would engage in finding a resolution.

His public position was that the only path forward was a Biden-McCarthy brokered agreement. His private position, delivered to Biden by phone in the weeks before negotiations accelerated, was the exact same, people familiar with the call said.

But McConnell’s suggestion, delivered during the Oval Office meeting between the top four congressional leaders, that Biden and McCarthy shrink the number of players involved in the talks did mark a critical contribution.

Biden acquiesced to the request and soon appointed Young, Terrell and Ricchetti to run point on the negotiations that were running dangerously close to the brink. McCarthy tapped McHenry and Republican Rep. Garret Graves of Louisiana, launching a rolling series of weeks.

Still, the level of trust with McCarthy would remain a work in progress – one put to the test by the top two principals and their negotiating teams. While the president and the White House’s team of negotiators were veterans of high-stakes showdowns between the White House and Congress, this was McCarthy’s first time in the driver’s seat.

As Biden and McCarthy’s relationship – always framed as professional, but hardly close – developed, Ricchetti became a key and quiet conduit between them. He also worked on critical pieces directly with McHenry.

Graves, who brought a significant level of energy expertise to the table, also grew up in the same part of Louisiana as Young and now represents the district where her parents live. The verbal jousting over who crafted the best gumbo became a running bit between the two in public.

Young and McHenry, who both have young children, started what became regular phone calls during daycare dropoff, as Terrell maintained constant contact with McCarthy’s chief of staff, long time Washington hand Dan Meyer.

“It’s like, you go camping with somebody, right? You’ve seen them in the morning before they’ve brushed their teeth and their hair’s a mess and you have to kind of figure out how to put up the tent in the rain,” Terrell said. “There’s just no doubt about it that you go through that experience and it inures to your benefit. It is how you grow and you bring more layers to your relationship.”

‘A clear runway’

From their earliest meetings with House Republican negotiators, White House officials made clear that anything less than a two-year debt-ceiling increase was a non-starter.

The message, according to a senior administration official, was straightforward: “If you think we’re doing this before an election, you’re out of your mind.”

“I promise you, we did not spend much time at all talking about that date,” Young said.

Reaching an agreement that would eliminate the possibility of another debt ceiling fight for the rest of Biden’s term was a top priority for negotiators. As was averting a potential government shutdown later this year.

The deal Biden will sign into law on Saturday does both, incentivizing lawmakers to fully fund the government or face the indiscriminate meat cleaver of 1% across-the-board cuts to both defense and nondefense spending next year.

While the legislation doesn’t mean the White House won’t still face significant fights with Congress, including over supplemental funding for defense and Ukraine assistance, it does clear the decks of the most politically perilous fights for a White House eager to focus on implementing and selling Biden’s first two years of legislative accomplishments.

“By striking this deal, we now have a clear runway to sell that economic vision and implement historic investments across the major pieces of legislation – infrastructure, CHIPS, the IRA,” Zients said.

That shifting focus was on the president’s mind as he walked into his chief of staff’s office late Thursday night, accompanied by his dog Commander, to watch the votes come in on the Senate floor alongside members of his senior staff.

The vote marked the end of a long day spent congratulating hundreds of cadets from the Air Force Academy in Colorado and the culmination of a monthslong negotiation that monopolized his attention and overshadowed a critical foreign trip.

After asking what percentage of Democrats were voting for the bill and as it became clear he had the votes to pass the debt ceiling package, Biden turned to his chief of staff and began discussing the next task: implementing the legislation he passed in his first two years – and which his deal with McCarthy had spared.

CORRECTION: This story has been updated to correct the description of White House budget chief Shalanda Young’s ties to the Louisiana district represented by Republican Rep. Garret Graves.