More than half of the world’s largest lakes and reservoirs have lost significant amounts of water over the last three decades, according to a new study, which pins the blame largely on climate change and excessive water use.

Roughly one-quarter of the world’s population lives in the basin of a drying lake, according to the study by a team of international scientists, published Thursday in the journal Science.

While lakes cover only around 3% of the planet, they hold nearly 90% of its liquid surface freshwater and are essential sources of drinking water, irrigation and power, and they provide vital habitats for animals and plants.

But they’re in trouble.

Lake water levels fluctuate in response to natural climate variations in rain and snowfall, but they are increasingly affected by human actions.

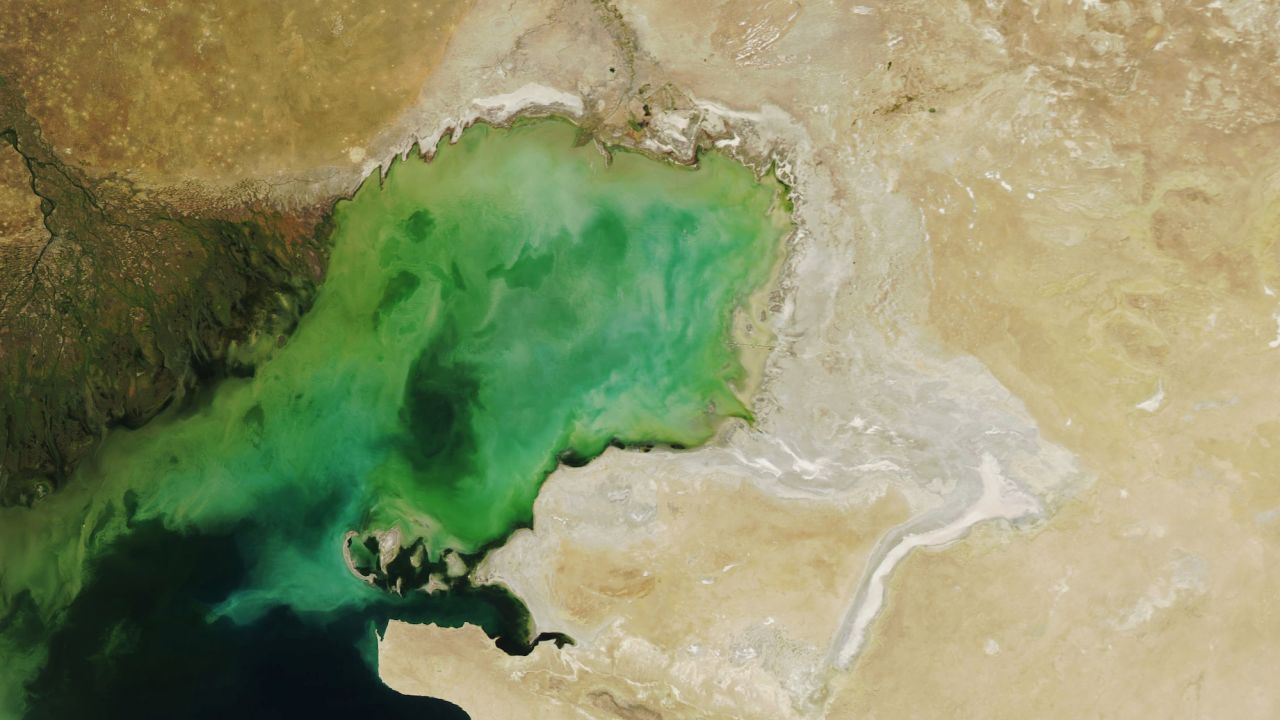

Across the world, the most significant lakes are seeing sharp declines. The Colorado River’s Lake Mead in Southwest US has receded dramatically amid a megadrought and decades of overuse. The Caspian Sea, between Asia and Europe – the world’s largest inland body of water – has long been declining due to climate change and water use.

The shrinking of many lakes has been well documented, but the extent of change – and the reasons behind it – have been less thoroughly examined, said Fangfang Yao, the study’s lead author and a visiting scholar at the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences at the University of Colorado Boulder.

The researchers used satellite measurements of nearly 2,000 of the world’s largest lakes and reservoirs, which together represent 95% of Earth’s total lake water storage.

Examining more than 250,000 satellite images spanning from 1992 to 2020, along with climate models, they were able to reconstruct the history of the lakes going back decades.

The results were “staggering,” the report authors said.

They found that 53% of the lakes and reservoirs had lost significant amounts of water, with a net decline of around 22 billion metric tons a year – an amount the report authors compared to the volume of 17 Lake Meads.

More than half of the net loss of water volume in natural lakes can be attributed to human activities and climate change, the report found.

The report found losses in lake water storage everywhere, including in the humid tropics and the cold Arctic. This suggests “drying trends worldwide are more extensive than previously thought,” Yao said.

Different lakes were affected by different drivers.

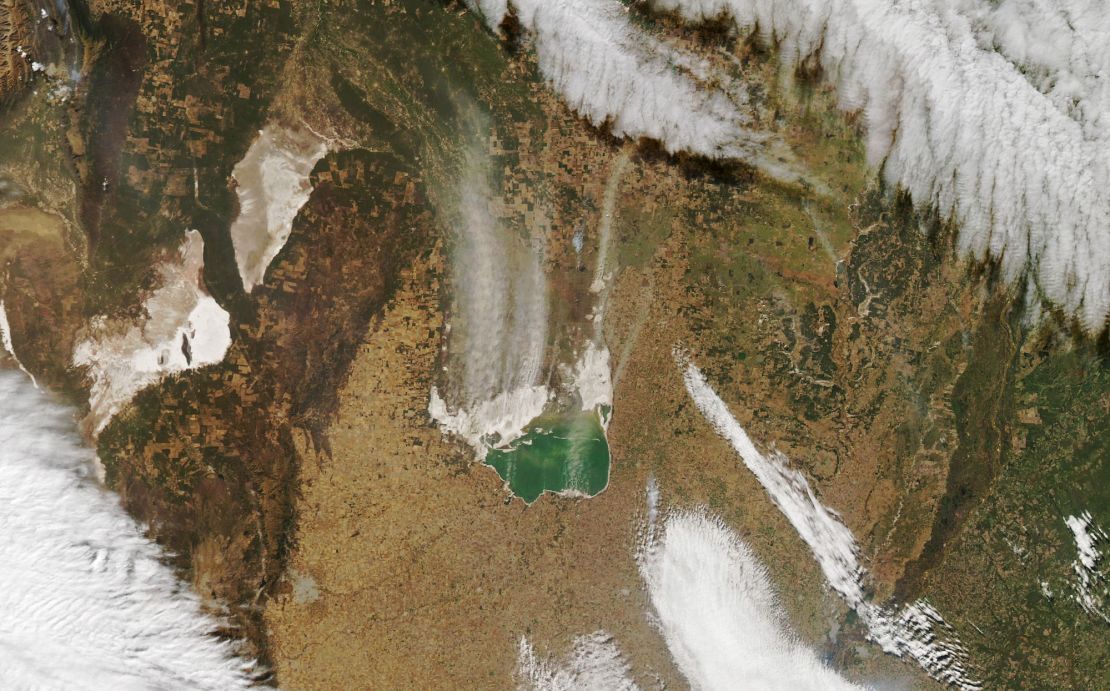

Unsustainable water consumption is the predominant reason behind the shriveling of the Aral Sea in Uzbekistan and California’s Salton Sea, while changes in rainfall and runoff have driven the decline of the Great Salt Lake, the report found.

In the Arctic, lakes have been shrinking due to a combination of changes in temperature, precipitation, evaporation and runoff.

“Many of the human and climate change footprints on lake water losses were previously unknown,” Yao said, “such as the desiccations of Lake Good-e-Zareh in Afghanistan and Lake Mar Chiquita in Argentina.”

Climate change can have an array of impacts on lakes. The most obvious, Yao said, is to increase evaporation.

As lakes shrink, this can also contribute to an “aridification” of the surrounding watershed, the study found, which in turn increases evaporation and accelerates their decline.

For lakes in colder parts of the world, winter evaporation is an increasing problem as warmer temperatures melt the ice that usually covers them, leaving the water exposed to the atmosphere.

These changes can have cascading effects, including a decrease in water quality, an increase in toxic algal blooms and a loss of aquatic life.

“An important aspect that is not often recognized is the degradation in water quality of the lakes from a warmer climate, which puts stress on water supply for communities that rely on them,” Yao said.

For reservoirs, the report found that the biggest factor in their decline is sedimentation, where sediment flows into the water, clogging it up and reducing space. It’s a “creeping disaster,” Yao said, happening over the course of years and decades.

Lake Powell, for instance – the second-largest human-made reservoir in the US – has lost nearly 7% of its storage capacity due to sediment build-up.

Sedimentation can be affected by climate change, he added. Wildfires, for example, which are becoming more intense as the world warms, burn through forests and destabilize the soil, helping to increase the flow of sediment into lakes and reservoirs.

“The result of sedimentation will be that reservoirs will be able to store less water, thereby becoming less reliable for freshwater and hydroelectric energy supply, particularly for us here in the US, given that our nation’s reservoirs are pretty old,” Yao said.

Not all lakes are declining; around a third of lake declines were offset by increases elsewhere, the report found.

Some lakes have been growing, with 24% seeing significant increases in water storage. These tended to be lakes in less populated regions, the report found, including areas in the Northern Great Plains of North America and the inner Tibetan Plateau.

The fingerprints of climate change are on some of these gains, as melting glaciers fill lakes, posing potential risks to people living downstream from them.

In terms of reservoirs, while nearly two thirds experienced significant water loss, overall there was a net increase due to more than 180 newly filled reservoirs, the report found.

Catherine O’Reilly, professor of geology at Illinois State University, who was not involved with the study, said this new research provides a useful long term data set that helps untangle the relative importance of the factors driving the decline of lakes.

“This study really highlights the impact of climate in ways that bring it close to home – how much water do we have access to, and what are the options to increase water storage?” she told CNN.

“It’s a little scary to see how many freshwater systems are unable to store as much water as they used to,” she added.

As many parts of the world become hotter and drier, lakes must be managed properly. Otherwise climate change and human activities “can lead to drying sooner than we think,” Yao said.