Editor’s Note: Elizabeth Grey is a writer finishing her first book, a memoir on addiction. The views expressed in this commentary are the author’s own. View more opinion on CNN.

“Don’t read it,” I tell myself every time I get an alert on my phone about E. Jean Carroll’s trial against the 45th president for allegedly defaming her when he denied her accusations of rape. I can ill-afford an episode right now. I’m days away from finishing a first draft of a book. I cannot be incapacitated so close to the finish line.

I’ve had traumatic responses to watching testimony at rape trials in the past. Days of my life are stolen. So I don’t read about them. If they’re being covered on TV, I leave the room. I must protect myself. I have a life now in which I function. It’s fantastic, but fragile.

It wasn’t my rape that did me in. It was testifying in court that broke me. After the rape, my confidence was still intact. I couldn’t have reported it otherwise. But after the trial, my confidence vanished. I became hyper-critical of myself, as if the defense attorney had set up shop in my own mind.

When I was 17, I reported a sexual assault. It occurred at a party while I was unconscious from alcohol poisoning. In 1983, the term “date rape” was not part of the vernacular. DNA evidence was a few years from being utilized.

We weren’t quite at the stage where people pointed out that rapists were the ones committing the crime.

Several months later, the case went to trial. I was on the witness stand for hours, cross examined by a defense attorney who seemed to thoroughly enjoy the process of dismantling me piece by piece. From where I sat, he was having a good time.

The result of my testimony was a $100 fine for the defendant for fornication. Perhaps the jury was swayed by his attorney’s characterization of me as the perpetrator’s “lover of the moment.”

As much as I’d like to believe things have changed for those who have to testify, I don’t believe they have.

Fifteen years passed before I understood that I never left the witness stand. For my audacity in reporting a rape, I was sentenced to life in a box.

Testimony in court is public. It’s bad enough to experience questioning about an assault in private. An audience makes it exponentially worse. Horrible moments of our lives and how defense attorneys frame them can become public fodder.

When an attorney forms a question, I can’t interrupt. The process requires that I sit there silently while he calls the shots. I must answer the most intrusive of queries.

At some point during my trial — because I was the one on trial, not the perpetrator — the defense attorney let slip out of nowhere that my father had left my mother.

My father had died two years previously. He and I were very close. Now I wasn’t just defending myself, I had to defend my dead father.

Several people in the courtroom appeared to be there for entertainment. I remember looking up and catching the eye of a boy from high school. He wasn’t a friend of mine. I wanted to know why people like him were privy to my public evisceration.

Sometimes I still see that boy’s face, leaning forward, listening for the next sordid detail. He’s with me as I write.

I tell myself at least I was spared an internet reaction. That is no small thing.

Many years later I made my way to therapy. There I learned I had something called post-traumatic stress disorder as a result of the trial.

Trauma is difficult to describe. I now understand that memories get filed in the wrong drawer of the brain. After the trial, I was often unable to distinguish the present from 1983. Whenever I was having a conversation and formed a response, I went on high alert. I wasn’t in the present moment. In my mind’s eye, I was in that chair, in that courtroom.

Every questioner became a defense attorney. You could ask me something like, “Where did you grow up?” and I was back in the courtroom. All questions had the potential to destroy. I was girding myself for the next verbal assault.

I wasn’t cognizant of this dilemma until one day I had a breakthrough and could see where my mind held me hostage. I could see I was always answering from the witness stand.

The goal of a defense attorney seems to be to break the survivor giving testimony. To take away any credibility to her story. To craft a different version than the one she tells. The attorneys individually fine-tune it, but the basic narrative too often goes like this:

You are crazy, you want attention, you didn’t mind, you led him on, you’re angry he rejected you, you’re seeking revenge, why didn’t you fight, it didn’t happen, you’re not stable.

Which means when victims report a crime, there is every reason to dread a bad outcome.

Even if a rapist is charged, prosecuted and sentenced to prison time (a girl can dream), the survivor must live with the attorney’s words ringing in her ears the rest of her life.

We get the life sentence.

When I reported that crime, I did it for one reason: If I didn’t, he was free to do it again. It does beg the question of why a 17-year-old girl had to take the responsibility of ensuring the future safety of women, but there you have it.

I did my part and learned my life was worth a hundred-dollar bill.

The truth is, rape in our society seems to be acceptable. If it weren’t, there would be a system in place that didn’t destroy survivors. There would be a way to testify that didn’t leave us in ruins afterwards.

That system could be a reality if people called their district attorneys’ offices and their lawmakers to ask them what they’re doing to change how victims of crime are questioned in court. If they pushed legislators to pass laws allowing for sexual assault victims to testify via two-way closed circuit television – just as children are when they’re afraid to appear in open court – as well as laws that impose stricter minimum sentencing requirements for sexual assault in every state. And they could remind judges of their duty to hold attorneys in contempt when badgering a victim.

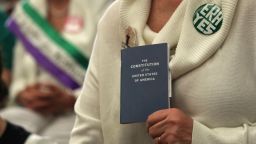

Carroll, 79, never went to the police about her alleged rape in 1996 because, she said on the stand last week, she was“ a member of the Silent Generation” and conditioned to keep quiet. I don’t blame her. How could I ask any survivor to go through what I experienced?” The current trial concerns her civil suit against former President Donald Trump for making public statements many years later denying her claims of what happened in the 1990s. (Trump has denied all wrongdoing.)

Get Our Free Weekly Newsletter

- Sign up for CNN Opinion’s newsletter

- Join us on Twitter and Facebook

On Friday, I got a text from my friend Paul Slansky.

“This was epic!” he wrote. I see a screenshot of text of an exchange between Carroll and Joseph Tacopina, defense attorney for Trump.

I told myself I’d stop reading it if I started to panic. But a miracle occurred. I was cheered by what I saw.

“You can’t beat up on me for not screaming,” Carroll told Tacopina.

Tacopina had been pointedly questioning her about not screaming while she alleged the rape was occurring in a dressing room at Bergdorf Goodman. This is a defense attorney Top Ten classic. Carroll retorted, “I’m telling you: He raped me whether I screamed or not.”

I felt like she was sticking up for teenage me. But it’s also not lost on me that 40 years later, survivors are still doing the heavy lifting.

The National Sexual Assault Hotline is 1-800-656-4673 and provided by RAINN (Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network) 24/7.