TikTok is fighting to stay alive in the United States as pressure builds in Washington to ban the app if its Chinese owners don’t sell the company.

But the wildly popular platform, developed with homegrown Chinese technology, isn’t accessible in China. In fact, it’s never existed there. Instead, there’s a different version of TikTok — a sister app called Douyin.

Both are owned by Beijing-based parent company ByteDance, but Douyin launched before TikTok and became a viral sensation in China. Its powerful algorithm became the foundation for TikTok and is key to its global success.

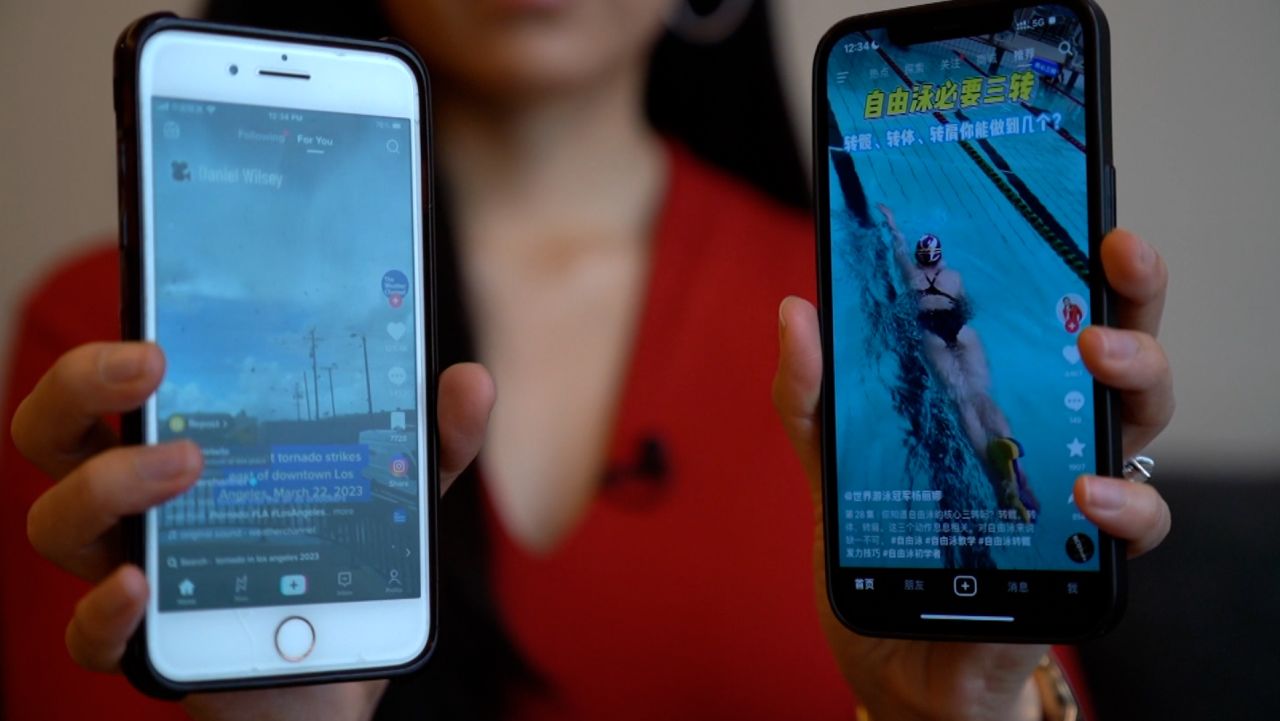

But the two platforms, similar on the surface, play by starkly different rules.

Here’s what you need to know about Douyin and ByteDance:

It’s really popular

Douyin has a whopping 600 million users a day. Like TikTok, it’s a short-form video app.

Launched in 2016, Douyin was the major money spinner for ByteDance years before TikTok, raking in revenue through in-app tipping and livestreaming.

ByteDance was founded by Zhang Yiming, a former Microsoft employee, and first became known for its news app Jinri Toutiao or “Today’s Headlines,” which debuted in 2012 soon after the company was founded.

Toutiao created customized news feeds for each user. People quickly got hooked, with users averaging more than 70 minutes a day on the platform.

ByteDance applied a similar formula to Douyin.

Then in 2017, the privately-owned tech company bought a US-based video startup and released TikTok as the overseas version of Douyin. It also bought popular lip syncing app musical.ly, and moved those users onto TikTok in 2018.

The app’s popularity has since gone global. In 2021, TikTok reached more than 1 billion monthly active users around the world.

Beauty filters are everywhere

The TikTok and Douyin interfaces look similar, but when users turn on their cameras, one difference becomes clear: Douyin has an automatic beauty filter, which smooths out skin and often changes the shape of a person’s face.

Women in China have long faced huge pressure to conform to beauty standards that emphasize a slim figure, large eyes, dewy skin and high cheekbones.

There is surging demand for plastic surgery. Between 2014 and 2017, the number of people getting plastic surgery in China more than doubled. Meanwhile, beauty apps compete to create filters that show users more beautiful versions of themselves.

While TikTok also has beauty filters, users can select them when filming. They do not launch automatically.

It’s made for shopping

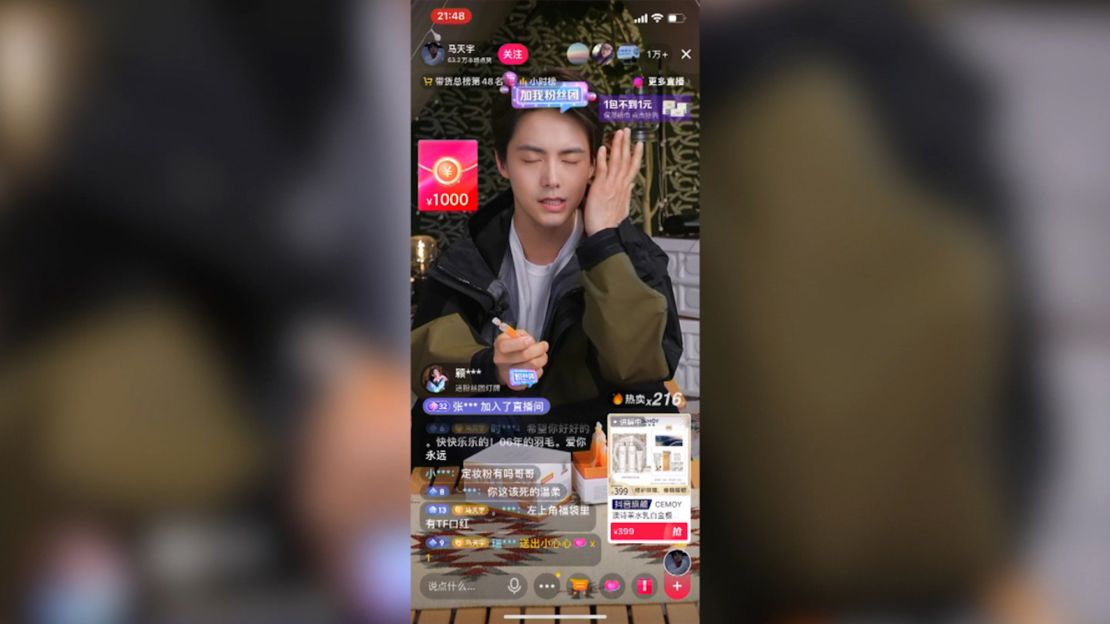

Another major difference between TikTok and Douyin is China’s massive online shopping market.

Livestreaming sales of products is a multibillion-dollar industry in mainland China, and was given a major boost during the pandemic.

As of June last year, there were more than 460 million livestreaming e-commerce users in mainland China, according to the Academy of China Council for the Promotion of International Trade, a body affiliated with Beijing’s commerce ministry.

Douyin is a major platform for livestreamers, along with Taobao, Alibaba’s (BABA) eBay-like online marketplace.

I

n-app shopping is made easy: Products and discounts are displayed on-screen during livestreams, with purchases just a swipe or a click away.

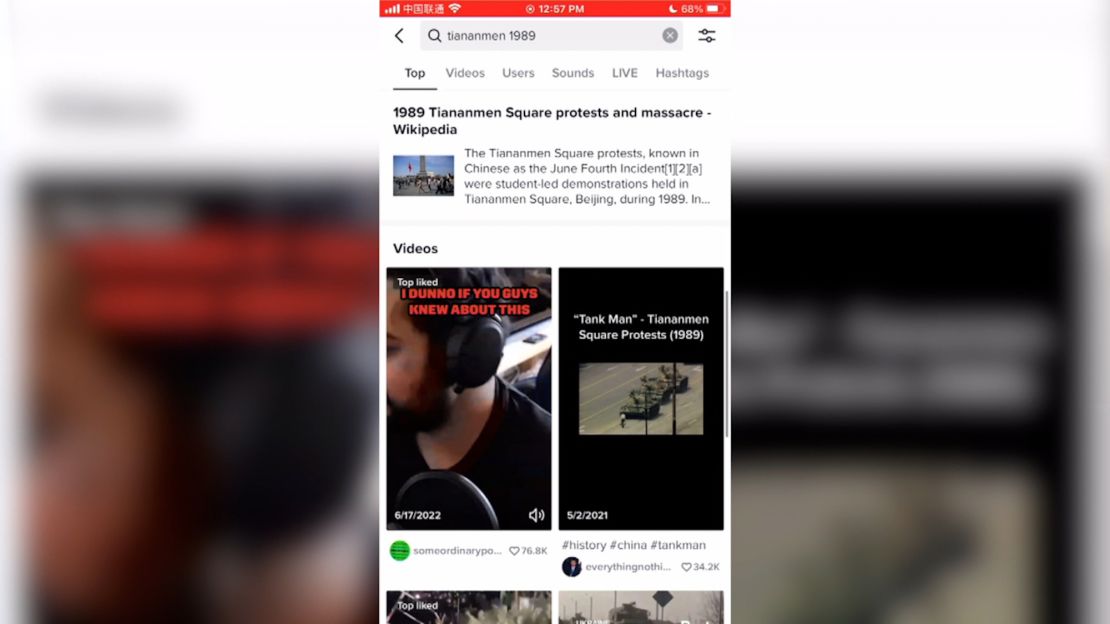

Censorship is rampant

China has one of the world’s strictest censorship regimes, and Douyin must follow the rules.

Internet watchdogs crack down regularly on online dissent and block politically sensitive information.

When CNN searched “Tiananmen 1989” in Douyin, nothing came up.

The Tiananmen massacre, in which Chinese troops cracked down brutally on pro-democracy protesters in Beijing, has been wiped from China’s history books. Any discussion of the event is strictly censored and controlled.

When CNN searched the same phrase in TikTok, it yielded many results including videos of users talking about what happened and a brief Wikipedia blurb summarizing the event.

“It’s so interesting to see this contradiction in this one company [ByteDance] with these two faces,” said Duncan Clark, chairman and founder of investment advisory BDA China.

Restrictions for young users

Another key difference: Douyin takes a much stricter line on younger users.

Users under 14 can access only child-safe content and use the app for just 40 minutes a day and. They can’t use the app from 10 p.m. to 6 a.m.

For years, China has tried to curb video game addiction and other unhealthy online habits. It announced a curfew for online gaming for minors in 2019, before outright banning online gaming during weekdays for minors.

Even on most weekends, users under 18 are only allowed to play for three hours.

“There’s been very much a laissez-faire attitude in the US towards content, even content targeting teenagers and vulnerable people,” said Clark. “The Chinese government has been much more leaning into regulation at early stages in the growth of Douyin, particularly protecting younger people.”

TikTok took some similar steps earlier this month, announcing that every user under 18 will soon have their accounts default to a one-hour daily screen time limit, though teenage users will be able to turn off this new default setting.

Not alone

TikTok is not the only Chinese-owned platform finding viral success in the United States.

Of the top 10 most popular free apps on Apple’s (AAPL)US app store, four were developed with Chinese technology.

Besides TikTok, there’s also shopping app Temu, fast fashion retailer Shein and video editing app CapCut, which is also owned by ByteDance.

TikTok remains hugely popular in the United States, with more than 150 million monthly users — almost half of the country’s population.

It remains to be seen whether TikTok can convince US lawmakers that it poses no threat — but the showdown in Washington has highlighted larger questions about security and data privacy that could see other apps come under fire.

These apps could be next, said Clark. He said the US needs a “more sophisticated framework for regulating the big tech companies,” given the number of US investors and users on foreign platforms.

“They need to also think about how high they’re gonna raise the bar for Chinese investment in the US, and the consequences of completely excluding four of the top ten apps,” said Clark.

“What’s gonna replace them? And how is that going to play out? And how is that equitable to the investors in those apps versus US players?” he added. “It’s a mess.”

— CNN’s Riley Zhang contributed reporting.