Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

A nearby star system is helping astronomers unravel the mystery of how water appeared in our solar system billions of years ago.

Scientists observed a young star, called V883 Orionis, located 1,300 light-years away using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array of telescopes, or ALMA, in northern Chile.

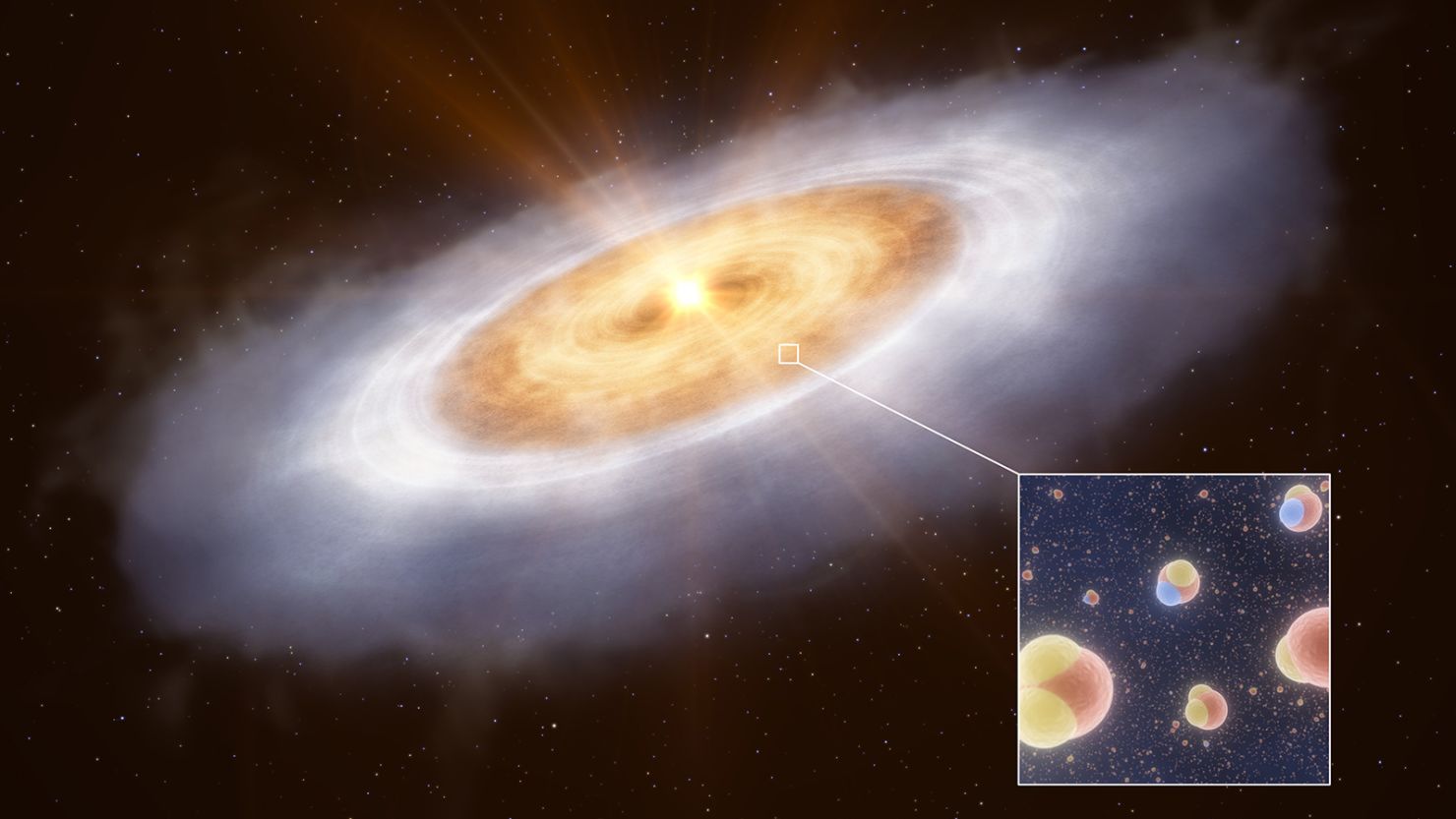

The star is surrounded by a planet-forming disk of cloud of gas and dust leftover from when the star was born. Eventually, material in the disk comes together to form comets, asteroids and planets over millions of years.

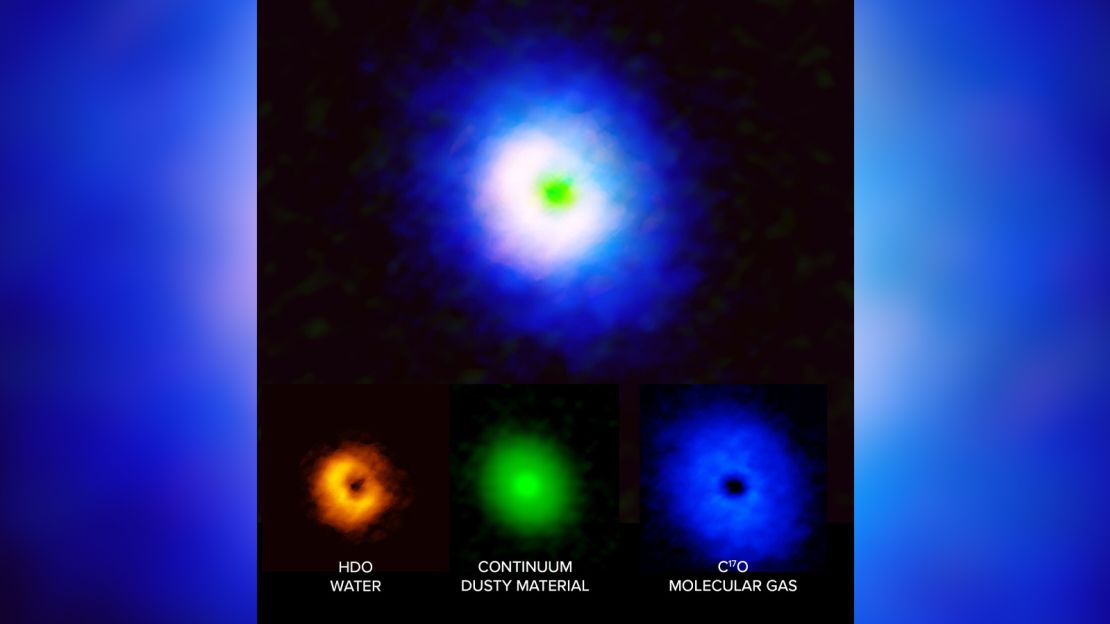

A team of researchers used ALMA to measure chemical signals in the planet-forming disk, and they detected gaseous water, or water vapor. Their detection allowed the astronomers to trace the water’s journey from the gas clouds that formed the star and will eventually give rise to planets.

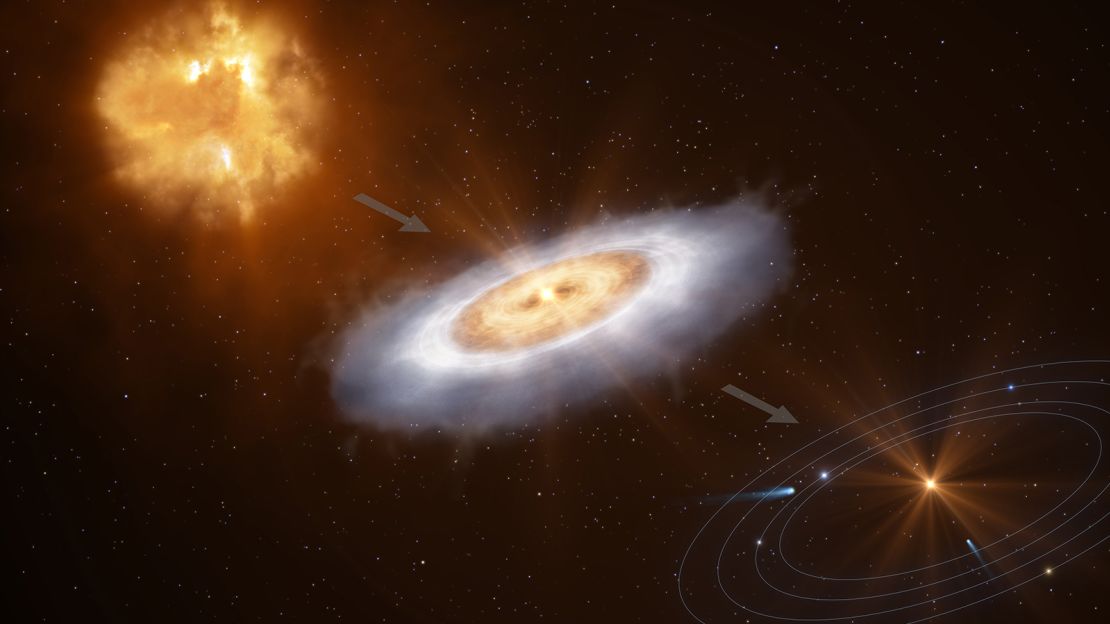

Their findings, published Wednesday in the journal Nature, suggests that comets formed from the sun’s planet-forming disk could have brought water to Earth. That means the water on Earth could actually be older than our sun, which is 4.6 billion years old.

“We can now trace the origins of water in our Solar System to before the formation of the Sun,” said lead study author John J. Tobin, an astronomer at the National Radio Astronomy Observatory, in a statement.

Typically, water molecules are made of one oxygen atom combined with two hydrogen atoms.

The research team studied a variation called heavy water, detected in V883 Orionis’ disk? where one of the hydrogen atoms is replaced by a heavy isotope called deuterium. The water we’re used to and heavy water both form in different scenarios, and their ratios can be used by researchers to trace when and where the water molecules formed.

Astronomers believe comets might have been responsible for delivering water to Earth early in its history by colliding with the planet because some comets have ratios similar to water on Earth.

Comets are large celestial objects made of dust and ice that orbit stars.

During their study of V883 Orionis, the researchers realized the missing link between the young stars born from clouds of gas and dust that include water molecules, and the comets also created from those same clouds swirling around newborn stars.

“V883 Orionis is the missing link in this case,” said Tobin in the statement. “The composition of the water in the disc is very similar to that of comets in our own Solar System. This is confirmation of the idea that the water in planetary systems formed billions of years ago, before the Sun, in interstellar space, and has been inherited by both comets and Earth, relatively unchanged.”

Detecting water molecules in planetary disks can be a difficult task.

“Most of the water in planet-forming discs is frozen out as ice, so it’s usually hidden from our view,” said study coauthor Margot Leemker, a doctoral student at Leiden Observatory in the Netherlands, in a statement.

Gaseous water is easier to detect than ice because the molecules emit radiation as they move.

The disk around V883 Orionis is unusually warm due to outbursts of energy released by the star, which turned the ice to gas and enabled the researchers to detect it, Tobin said.

The team detected at least 1,200 times the amount of water in Earth’s oceans in the planet-forming disk.

Astronomers are eager to use the Extremely Large Telescope, or ELT, and its first-generation instrument Mid-infrared ELT Imager and Spectrograph, or METIS, for these kinds of observations in the future. The ELT is currently under construction in Chile and is expected to be ready in 2028.

“This will give us a much more complete view of the ice and gas in planet-forming discs,” Leemker said.

![Based on new evidence from the NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope, this illustration reflects the conclusion that the exoplanet LHS 475 b is rocky and almost precisely the same size as Earth. The planet whips around its star in just two days, far faster than any planet in the Solar System. Researchers will follow up this summer with additional observations with Webb, which they hope will allow them to definitively conclude if the planet has an atmosphere. LHS 475 b is relatively close, 41 light-years away, in the constellation Octans. [Image Description: Illustration of a planet and its star on a black background. The planet is large, in the foreground at the centre, and the star is smaller, in the background and also at the centre. The planet is rocky. The top quarter of the planet (the side facing the star) is lit, while the rest is in shadow. The star is bright yellowish-white, with no clear features.]](https://media.cnn.com/api/v1/images/stellar/prod/230111134727-01-james-webb-space-telescope-exoplanet-confirmation.jpg?c=16x9&q=h_144,w_256,c_fill)