When Ben Ratner’s family signed up in 2021 to be extras in the movie “White Noise,” they thought it would be a fun distraction from their day-to-day life in blue-collar East Palestine, Ohio.

Ratner, 37, is in a traffic jam scene, sitting in a line of cars trying to evacuate after a freight train collided with a tanker truck, triggering an explosion that fills the air with dangerous toxins. In another scene, his father wears a trench coat and hat while people walk across an overpass to get out of town. Directors told the group they wanted them to look “forlorn and downtrodden” as they escape the environmental disaster.

The 2022 movie was shot around Ohio and is based on a novel by Don DeLillo. The book was published in 1985, shortly after a chemical disaster in Bhopal, India, that killed nearly 4,000 people. The book and film follow the fictional Gladney family – a couple and their four kids – as they flee an “airborne toxic event” and then return home and try to resume their normal lives.

Ratner tried to rewatch the movie a few days ago and found that he couldn’t finish it.

“All of a sudden, it hit too close to home,” he said.

Ratner and his family – his wife, Lindsay, and their kids, Lilly, Izzy, Simon and Brodie – are living the fiction they helped bring to the screen.

Officials ordered them to evacuate their home last week, a day after a Norfolk Southern train carrying 20 cars of hazardous materials slid off the rails and caught fire, threatening to explode. The National Transportation Safety Board is still investigating the cause of the incident.

“The first half of the movie is all almost exactly what’s going on here,” Ratner said Wednesday, four days into their evacuation.

In a way, the movie has provided a point of grim humor about the situation facing the residents of East Palestine – the joke no one wanted to make.

“Everybody’s been talking about that,” Ratner said of his friends and neighbors who are keeping in close touch through the crisis. “I actually made a meme where I superimposed my face on the poster and sent it to my friends.”

Scholars who study DeLillo’s work say they are not surprised by the collision of life and art. His work is often described as prescient, said Jesse Kavadlo, an English professor at Maryville University in St. Louis and president of the Don DeLillo Society.

“The terrible spill now is, of course, a coincidence. But it plays in our minds like life imitating art, which was imitating life, and on and on, because, as DeLillo suggests in ‘White Noise’ as well, we have unfortunately become too acquainted with the mediated language and enactment of disaster,” Kavadlo said.

A crushing blow

The night of February 3, Ratner was watching his daughter’s basketball game at the local high school when the crash happened. He didn’t hear it over the noise of the game, but when they walked out of the building, he could see the massive blaze. He shot a few seconds of video on his cell phone.

His family returned to their house, which sits less than a mile from the crash site. Throughout the night, he said, they heard sirens but got little information. “We weren’t sure exactly what the danger was.”

While his family slept, he stayed up, nervously watching the fire and the news.

The next morning, activity around the site had picked up. “There was a lot of commotion, helicopters and people hightailing it out of town, and it was it was a little intense,” he said.

His wife and kids headed to stay with his wife’s parents, who live about 2 miles from the crash site. Ratner went to work running the coffee shop he and his wife own, LiB’s Market, in nearby Salem.

By that afternoon, an official alert warned that people needed to move even farther, beyond a 2-mile radius. Roughly half of the town’s 4,800 residents had to evacuate.

A friend offered to let them stay in their pool house. They later moved to another friend’s house next to their café.

School was canceled for the week. They got their dog out of the house, but they had to leave the pet turtle behind.

For now, they’re keeping their distance. But even after they go back, they have to decide whether they’ll stay.

East Palestine is in an economically depressed area, Ratner said, but it had been on a rebound. He and his wife had been considering opening another café there, but now they’re worried that plan is in jeopardy.

“That’s where we’ve been raising our kids, finishing college, buying a business, and that’s been our place,” he said. “In the future, are we going to have to sell the house? Is it worth any money at this point?”

A town wonders what it’s coming home to

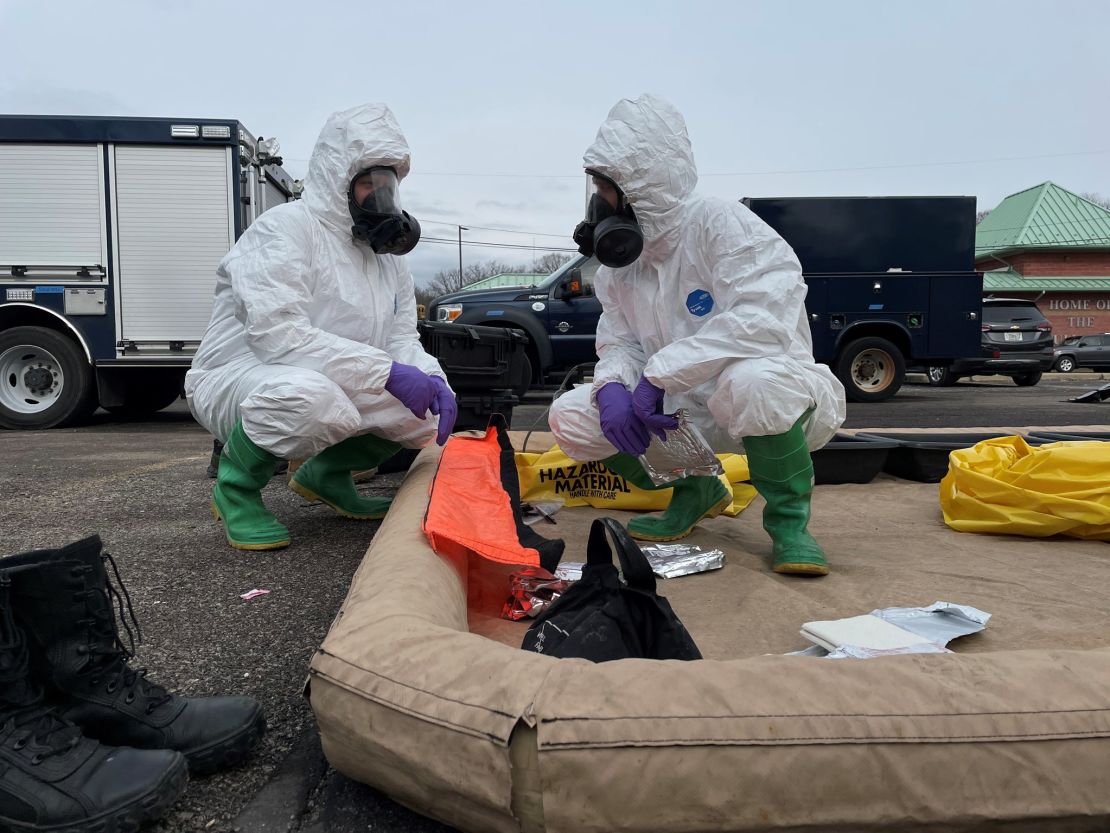

Five of the tankers on the train that overturned last week were carrying liquid vinyl chloride, which is extremely combustible. Last Sunday, they became unstable and threatened to explode. First responders and emergency workers had to vent the tankers, spill the vinyl chloride into a trench, and then burn it off before it turned the train into a bomb. Authorities feared that an explosion could send shrapnel up to a mile away.

But that didn’t happen. The controlled burn worked and the evacuation order for East Palestine residents was officially lifted Wednesday after real-time air and water monitoring did not find any contaminant levels above screening limits.

“All of the readings we’ve been recording in the community have been at normal concentrations, normal backgrounds, which you find in almost any community,” James Justice, a representative of the US Environmental Protection Agency, said at a briefing Wednesday.

Although authorities have assured the residents that any immediate danger has passed, some residents have yet to return home. Ratner said they’re worried about longer-term risks that environmental officials are only beginning to assess.

Real-time air readings, which use handheld instruments to broadly screen for classes of contaminants like volatile organic compounds, showed that the air quality near the site was within normal limits.

The decision to lift the evacuation order was based on analysis of air monitoring data, according to Charles Rodriguez, community involvement coordinator for the EPA’s Region 5 office.

Up to this point, officials have been looking for large immediate threats: explosions or chemical levels that could make someone acutely ill.

“Under this phase, it’s been the emergency response,” Kurt Kollar of the Ohio EPA’s Office of Emergency Response said Wednesday. “As you see the emergency services go back home, off-site, Ohio EPA is going to remain involved through our other divisions that oversee the long-term cleanup of these kinds of spills.”

The cleanup and monitoring of the site, he said, could take years.

Watching for long-term dangers

Although the explosion risk is past, Ratner said, people who live in East Palestine want to know about the chemical threats that might linger.

Fish and frogs have died in local streams. People have reported dead chickens and shared photos of dead dogs and foxes on social media. They say they smell chemical odors around town.

When asked at Wednesday’s briefing about exactly what spilled, representatives from Norfolk Southern listed butyl acrylate, vinyl chloride and a small amount of non-hazardous lube oil.

“Butyl acrylate is a lot of what we’re gathering information on,” said Scott Deutsch, a regional manager of hazardous materials at Norfolk Southern.

Butyl acrylate is a clear, colorless liquid with a strong, fruity odor that’s used to make plastics and paint. It’s possible to inhale it, ingest it or absorb it through the skin. It irritates the eyes, skin and lungs and may cause shortness of breath, according to the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health. Repeated exposure can lead to lung damage.

Vinyl chloride, which is used to make PVC pipes, can cause dizziness, sleepiness and headaches. It has also been linked to an increased risk of cancer in the liver, brain, lungs and blood.

Although butyl acrylate easily mixes with water and will move quickly through the environment, it isn’t especially toxic to humans, said Richard Peltier, an associate professor of environmental health sciences at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

“Vinyl chloride, however, has a specific and important risk in that is contains a bunch of chlorine molecules, which can form some really awful combustion byproducts,” Peltier said. “These are often very toxic and often very persistent in the environment.”

A spokesperson for Norfolk Southern acknowledged but did not respond to CNN’s request for more information on how much of these chemicals spilled into the soil and water.

The Ohio EPA says it’s not sure yet, either.

“Initially, with most environmental spills, it is difficult to determine the exact amount of material that has been released into the air, water, and soil. The assessment phase that will occur after the emergency is over will help to determine that information,” James Lee, media relations manager for the Ohio EPA, wrote in an email to CNN.

Lee said that after his agency has assessed the site, it will work on a remediation plan.

Vinyl chloride is unstable and boils and evaporates at room temperature, giving it a very short lifespan in the environment, said Dana Barr, a professor of environmental health at Emory University’s Rollins School of Public Health.

“If you had a very small amount of vinyl chloride that was present in an area, it would evaporate within minutes to hours at the longest,” she said.

“But the problem they’re facing here is that it’s not just a small amount, and so if they can’t contain what gets into the water or what gets into the soil, they may have this continuous off-gassing of vinyl chloride that has gotten into these areas,” Barr said.

“I probably would be more concerned about the chemicals in the air over the course of the next month.”

State officials said they would continue to monitor the site for exactly that reason. They are also continuing to try to dig and remove contaminated soil.

“Right now, we have a system set up. As the data comes, it is distributed to a network of people to look at both on an immediate-phase – ‘Hey, is there anything really alarming to look at’ – and those smaller numbers that really matter to long-term health,” Kollar said at Wednesday’s briefing.

He said the local health department would test residents’ wells to make sure their drinking water is safe. Officials are also offering to test the air in residents’ homes before they come back.

Norfolk Southern is funding a phone line for residents to speak to a toxicologist with the Center for Toxicology and Environmental Health, an environmental consulting firm.

No one is quite sure whether to trust the help, though, since it’s coming mostly from the company behind the spill. Some residents have already filed a class-action lawsuit against Norfolk Southern.

“We’re definitely signing up for the air testing of the home before we get in there,” Ratner said.

A disaster in real life

The first trains to pass since the accident started rolling through again midweek, Ratner said. The roar of the trains, a sound he used to tune out, is now jarring.

Even the sounds of loud trucks are “off-putting,” he said.

Ratner said it was fun to be part of a disaster movie – a stylized, darkly comedic Netflix streamer starring Adam Driver, Greta Gerwig and Don Cheadle.

In real life, the situation has been gutting.

“Those are great actors, but it was hard to see it as a put-on,” Ratner said.

He shares the sentiments of Lenny Glavan, a local tattoo artist, who wrote a letter to Norfolk Southern CEO Alan Shaw on Tuesday to express the town’s anger and frustration over the accident.

“You just ripped from us our small-town motto ‘A place you want to be,’ ” Glavan wrote.

Get CNN Health's weekly newsletter

- Sign up here to get The Results Are In with Dr. Sanjay Gupta every Friday from the CNN Health team.

“It may not be beach-front property, it may not even have the highest paying jobs, or much else to offer, but in my experiences in life, the place I and most people want to be is when you need a helping hand, a shoulder to cry on, a friend to pray with, or a place to call home East Palestine has always been that place to want to be,” he said in his note, which was publicly posted on Facebook.

“With the events in which have occurred, the railroad that gave this small town life has now taken the life, the heartbeat, the unity and that security that families or individuals long for in this wild world away … possibly indefinitely.”

Correction: A previous version of this story incorrectly spelled Kurt Kollar’s name.