Sitting in the back of a packed room in the Hamilton County Schools administration complex, Clara fought the urge to leave. She had taken the day off from her factory job to be there but was nervous to see a crowd of people supporting a board member who had referred to Latino students as a burden.

On that fall afternoon, the mother of three felt like she carried the weight of those parents who wanted to defend their children but couldn’t show up out of fear, or could not leave their workplaces early to attend the school board meeting. Latino families who call Chattanooga, Tennessee, and its surrounding towns home are not invisible, and they don’t want to be a regular target of racist rhetoric and unequal treatment, she told CNN.

“It hurts when someone speaks without really knowing our people and uses ill words to humiliate our children. It hurts because it’s hard to try to understand (English), be there, arrive on time and support my kids at school,” said Clara, 52, whose two younger sons attend schools in the district.

“I’m not leaving because I want a much better future for my children,” she said.

CNN agreed to only use Clara’s first name to protect her identity out of respect for her safety concerns.

In the months since a Hamilton County Schools school board member suggested the rising number of Latino students who speak little to no English were overwhelming schools, several activists and educators who spoke with CNN said they received anti-immigrant, racist and hateful messages after condemning the remarks.

In this county near the Tennessee-Georgia border, the growth in the Hispanic or Latino population has outpaced the national average. In the past decade, the number of residents who identified as Hispanic or Latino rose nearly 81% or more than 12,000 people, compared to 23% nationwide, according to US Census data.

While the county’s more than 366,000 residents largely identify as White and about 7.4% identified as Hispanic or Latino in the 2020 Census, their presence has pushed a community with a dark racial history to face the inequalities that persist and adapt to a new normal that goes beyond the fractured Black-White paradigm that has characterized the South for a long time.

Although there are ongoing efforts by the city and school officials to better serve Latino families, the demographic shift has also come with reminders of how heavily divided this region is and the fact that many Latinos live afraid of authorities because of their current or past immigration status.

In an interview with The Chattanoogan in late August, Rhonda Thurman suggested the rising number of Latino students who speak little to no English were overwhelming schools. Thurman is a long-time board member representing schools with a majority White student population. She is known for her conservative views as well as her stance on books that have been deemed “inappropriate” for children by some or labeled “critical race theory.”

“It is mind-boggling to me the burden it puts on the schools, the teachers and the taxpayers,” Thurman told the newspaper about the number of Latino students.

“Teachers tell me they cannot give the attention they deserve to the English-speaking students because they have to devote so much time to try to help the Hispanic students catch up,” she said according to the newspaper.

During the board meeting last month, members briefly discussed resources for Latino students offered by the school district or their interest in new initiatives. That was something that Clara said reinforced her frustration over the lack of support for Latino families and her conviction to overcome the fear that some people of color have toward those with conservative views.

“I’m not afraid of speaking up and share my opinion, it’s where we live. This is the South and this area is absolutely closed (minded) in many aspects,” she said.

A ‘small but very loud minority of extremists’

The Hamilton County Schools district comprises 76 institutions and serves 45,000 students. About 19% of students, or 8,702, are Hispanic but not all of them have limited English proficiency.

There are 5,039 students considered English Language Learners currently enrolled, data shows. Diego Trujillo, director of the district’s English as a New Language Program, said Spanish is the top language for ELL but students speak more than 100 different languages, including Arabic, Mandarin, Vietnamese and five Mayan dialects.

“When we think about English learners, there’s this association strictly to folks that are Spanish speaking, and when you look across the district we’re seeing a diversity of language,” Trujillo said.

The school district declined to comment specifically on Thurman’s comments. Thurman has denied that she specifically called children a burden. She told CNN the number of Latino students were “burdening the system” and the school district was dealing with things it had not faced before.

“Different people say different words and some people just jump on it because I happen to be a conservative and a Christian and some people just don’t like that,” Thurman said.

Semillas, a non-profit group focused on racial and educational justice for the Latino community, has called for Thurman’s resignation and for a new task force to create an action plan that would better support the needs of Latino students and parents. Their online petition has garnered nearly 1,400 signatures.

“While some programming has been developed over the years, Latinx community members have seen little to no proactive action to actually take a moment to meet and listen to the challenges and barriers Latinx and immigrant students and parents face each and every day,” said Mo Rodriguez-Cruz, the group’s co-founder and field director.

Taylor Lyons, co-founder of the local parent group Moms for Social Justice, said negativity toward Hispanic students is just the latest in a list of “hot button” issues that have been the focus of conservatives who live in the county. Over the past several years, Lyons said, conservatives have flooded school board meetings to fight mask and Covid-19 vaccine mandates as well as books in school libraries, which made her group subject of threats and accusations. In 2018, Moms for Social Justice launched an initiative to help teachers stock classrooms with books.

“What it tells us is that you have a small but very loud minority of extremists, who are very uncomfortable with the cultural change around them. They’re uncomfortable with the demographic change,” Lyons said.

‘We are becoming one’

In Chattanooga, the county seat that largely touts itself as progressive, residents are seeing the demographic shift manifest itself in many aspects of their lives.

At The Howard School, a high school that is the pride of the city’s Black community, numerous photos of its Black alumni decorate the hallways, but most of its current students speak Spanish and are of Guatemalan descent. Most evenings, families can sit on wooden bleachers at amateur soccer matches and cheer as Spanish-language music blasts on speakers. In the city’s Rossville Boulevard, there has been an influx of Guatemalan restaurants and other businesses that proudly display the country’s flag or its national soccer team jersey.

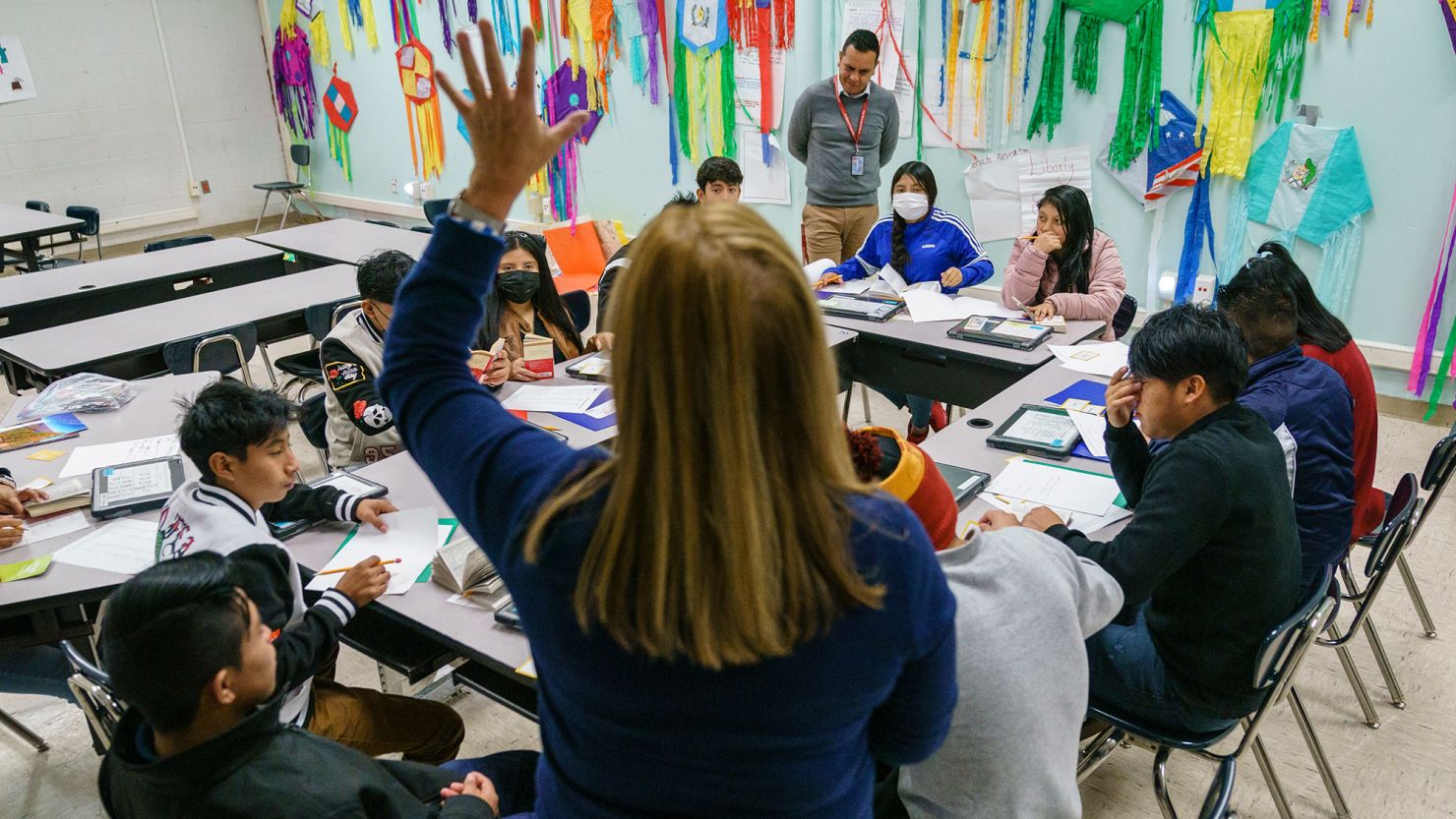

As the tensions spurred by changes in the student body came to light in recent school board meetings, students and teachers at two schools (Howard and East Side Elementary) in the district opted to keep focusing on creating an inclusive environment around them.

When Daisy Hernandez walked to her first class at The Howard School three years ago, she heard the chatter of her peers in English, Spanish and Mam, the Mayan language spoken in Guatemala and by her parents. There, the 17-year-old said she doesn’t see or feel the animosity that families like hers often experience while living in the South.

“I see Howard as a school that helps us out in knowing other people. I’ve seen Black students talk to Hispanic students. I think that’s beautiful because we are becoming one,” said Hernandez, who is the high school’s student body president.

The Howard School is the largest high school in the county and one of 10 schools in the district where Hispanic students surpass the number of students of any other racial or ethnic group. The number of English Language Learners at those schools this year represents 56% of all ELL students in the district.

For decades, the school was known for predominantly serving Black students, but enrollment data shows that at least half of the student body has been Hispanic in the past five school years.

At the start of the day, students listen to Assistant Principal Charles Mitchell read announcements in English and then in Spanish. The tradition, which began five years ago and required him to learn a new language, is one of the many ways “we go beyond our means just to include everybody,” Mitchell said.

Jose Otero, an English as a New Language teacher who has been at the school for the past four years, said most Hispanic students at Howard are Guatemalan and fall into two major groups. Like Hernandez, some children were born and raised in Chattanooga to immigrant parents, and others recently migrated from Guatemala, El Salvador or Mexico along with their families or by themselves.

All students, Hispanic or Black, have different realities and different experiences, Otero said, and one thing that helps them connect with each other has been sports, especially soccer.

Most of the 40 soccer players at Howard are Guatemalan and the larger school community has taken an interest in the team because they’ve been district champions in recent years, said Otero, who is also the school’s head soccer coach.

“The kids are starting to appreciate each other’s culture and want to be a part of it. I think with time, there’s gonna be more Guatemalan kids playing basketball and baseball and football, and there’s gonna be more Black kids playing soccer,” Otero said.

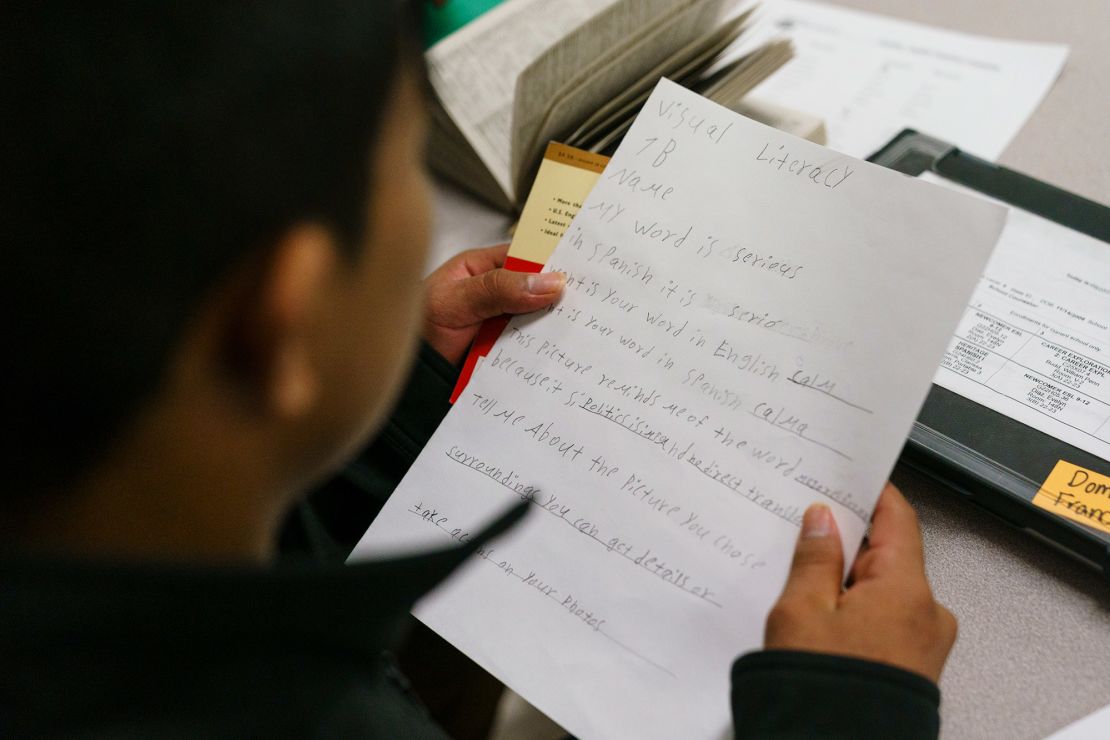

About two miles east of the high school, teacher Amanda Edens and her fifth-grade students at East Side Elementary finished reading “Esperanza Rising” by Pam Muñoz Ryan, a novel about a young girl who flees Mexico and settles in a farm camp in California.

Edens, whose Spanish is limited, said she used the book to teach her students the curriculum while also connecting with them. They are mostly Hispanic, she said, and they enjoyed giggling every time she pronounced the Spanish phrases and words scattered throughout the book.

The 37-year-old teacher is facing the challenging task of navigating a state law that requires public schools to teach only in English and serving a fast-growing number of students who are not fluent in the language.

But it’s something that Edens and other teachers in Hamilton County told CNN they embrace and said it’s far from being a burden.

“There’s obviously the challenge of how am I going to help a child attain educational success when we don’t speak the same language and I’m giving them complex fifth grade texts in English,” Edens said.

“It’s not necessarily an easy thing, but it is super rewarding when that child starts asking: ‘can I go to the restroom?’ in English, or when they’re speaking Spanish to me and I recognize what they’re saying well enough to communicate back,” she added. “But I’ve never felt burdened by that.”

At the elementary school, English as a New Language teachers “push in” or join the general education classes and work with small groups to reduce the time the students are away from their classroom. Trujillo, the director of the district’s English as a New Language Program, said that type of language acquisition model is part of the work he hopes to achieve at more schools as the district works to have ENL programs at most campuses. In the past, he said, students were taken to a different campus to get language instruction if their schools did not offer the program or had ENL teachers.

Andrea Bass, one of the ENL teachers at East Side Elementary, said the school staff respects and actively honors their students’ first language and culture. Many of the students are from Guatemala, and their families, who speak Spanish or Mayan dialects, are constantly engaged in their education despite the language barriers, she said.

When Edens, Bass and other teachers heard their students might have been referred to as a burden, they signed a letter calling the remarks “offensive to those students, their families, and those of us who teach them.”

“Our students don’t always have a voice and neither do their families,” Bass said. “I felt like it was my duty to speak up for them.”

That sense of duty comes from seeing how many parents are afraid to speak up or advocate for themselves but nonetheless put a lot of their trust in educators, Bass said.

Emphasizing ‘inclusion versus assimilation’

The Latino or Hispanic community in Hamilton County, including Chattanooga, has grown and changed since Clara moved there nearly two decades ago. Yet, the challenges many families face remain the same.

When Clara left her hometown in central Mexico, she went from working a desk job that required her to wear high heels and suits to factory jobs in Chattanooga, where sneakers and jeans are the norm. A change that was even more demoralizing, she said, would come on her son’s first day at school when she “realized that I had become illiterate.”

“I could not speak English, I couldn’t have a conversation with my son’s teacher. It was very frustrating,” she said.

Not much has changed for the increasing number of Latino families in the county, many who relocated from the neighboring state of Georgia after a state law that authorized police to investigate the immigration status and arrest undocumented immigrants went into effect in 2011. But city and school officials have launched initiatives in the past year hoping to address their needs.

The city created the Office of New Americans last year to connect immigrant and refugee communities with city resources, including translation services and helping them with citizenship and naturalization paperwork.

“It’s a way to make sure that we are empowering the people who are coming to Chattanooga and empowering our immigrant community to really be able to flourish,” said Esai Navarro, the office’s director.

Navarro said the key is “emphasizing inclusion versus assimilation.”

Meanwhile, the school district opened its International Welcome Center to assist international students with enrollment and connect them with support services. The center has helped 224 families since it opened last year.

The melting pot of races, languages and cultures that Hamilton County and Chattanooga are seeing is everything Hernandez, the high school student, has known ever since she was born. What some see as a new normal is simply her reality – something she recently wrote about in a poem:

“My left starred shoulder: red, white, blue”

“My right striped shoulder: Quetzal white, light blue..”

“A girl: two countries, one world, growing stronger, forever longer”