Europe is becoming increasingly reliant on China for trade, and many of its top companies are eager to invest in the world’s second biggest economy despite the disruption caused by Covid lockdowns.

But a souring relationship with an increasingly unpredictable Beijing, regret about the price Europe has paid for getting too close to Russia, and rising geopolitical tension has some EU officials considering whether the bloc should start to reduce its exposure.

It’s a calculation EU Council President Charles Michel weighed up on Thursday when he visited Chinese leader Xi Jinping for talks aimed at shoring up diplomatic ties.

At the meeting in the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, Xi told Michel that China was “ready to strengthen strategic communication and coordination with the European side,” according to Chinese state broadcaster CCTV.

A lot has happened since the last time an EU president — appointed by the leaders of the 27 EU member states — met with Xi in person four years ago.

The Covid-19 pandemic, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and tit-for-tat sanctions between China and EU lawmakers have strained relations since. The United States, which imposed controls on exports of semiconductors to China in October, is reportedly exerting pressure on Europe to adopt a similarly hard line.

Michel’s spokesperson, Barend Leyts, said in a statement last week that Michel’s visit provides a “timely opportunity” for Europe and China to engage on matters of “common interest.” He did not specify which subjects would be discussed.

But some within Europe are growing wary of close relations with China. The bloc has been badly burned this year by its historic reliance on Russia as its main energy supplier, and diversification has shot up the political agenda.

Speaking at a conference in Berlin on Wednesday, NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg said that the “dangerous dependency” of some countries on Russian natural gas should cause the alliance to “assess [its] dependencies on other authoritarian states, not least China.”

Those concerns bubbled up last month when German Chancellor Olaf Scholz flew to Beijing with a delegation of top business leaders to meet Xi, a move intended to shore up Germany’s second biggest export market after the US.

The bloc is in a similar bind.

“Any problems you have from a political and strategic level [between the EU and China], they tend to spill over to the economic level,” Ricardo Borges de Castro, associate director at the European Policy Centre, told CNN Business.

‘Too big to fail’

Both sides have a lot invested in their partnership. The total value of the goods trade between China and Europe hit €696 billion ($732 billion) last year, up by nearly a quarter from 2019.

China was the third largest destination for EU goods exports, accounting for 10% of the total, according to Eurostat data. China is Europe’s biggest source of imports, accounting for 22% in 2021.

“The European market’s importance as a destination for Chinese exports is around double that of the Chinese market for Europeans,” Jörg Wuttke, president of the EU Chamber of Commerce in China (EUCCC) wrote in a September report.

Overall, the relationship is simply “too big to fail,” according to Borges de Castro. Europe is not seeking to decouple from the lucrative Chinese market, he added.

“I don’t see [the EU’s strategy] as a decoupling strategy. I think the EU strategy, for the moment, is a diversification strategy… the lesson [from Russia] is that you cannot have a single provider,” he said.

Machinery, vehicles, chemicals, and other manufactured goods account for the vast bulk of goods traded between the two powers, according to Eurostat.

“European companies have done extremely well here and the overall long term outlook is very positive,” EUCCC Secretary General Adam Dunnett told CNN Business, adding that he expects European company revenues to keep growing in China over the next decade.

There are areas where Europe is dependent on Beijing, namely for the supply of rare earth metals required to make hybrid and electric vehicles, and wind turbines. Europe’s solar panels are also mostly manufactured in China.

But those dependencies shouldn’t be exaggerated, Dunnett said.

“When you look at some of the broader things that China exports to the EU such as furniture and consumer goods, a lot of those things you can get elsewhere,” he said.

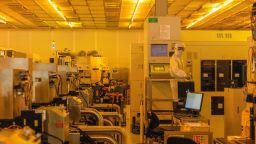

Even so, the United States may exert more pressure on Europe to pull away from China, Borges de Castro noted. In early October, Washington banned Chinese firms from buying its advanced chips and chip-making equipment without a license.

Benjamin Loh, the head of Dutch chipmaker ASM International, told the Financial Times on Wednesday that the US was “putting a lot of pressure” on the Dutch government to take a similarly tough stance.

The pressure may already be beginning to show. Germany last month blocked the sale of one of its chip factories to a Chinese-owned tech company because of security concerns.

‘Systemic rival’

Economic ties between Brussels and Beijing, though mutually beneficial, have frayed in other ways in recent years.

Last year, Chinese direct investment into the European Union dropped to its second lowest level since 2013, only behind 2020, according to analysis by the Rhodium Group, a research firm. It has fallen almost 78% since 2016.

“The level of Chinese investment in Europe is now at a decade low,” Agatha Kratz, director at Rhodium Group, told CNN Business, citing Beijing’s strict capital controls and greater scrutiny by EU regulators.

EU investment into China has also become more concentrated. Between 2018 and 2021, the top 10 European investors in China, including those from the United Kingdom, made up almost 80% of the continent’s total investment in the country, Rhodium Group data shows.

And just four German companies — automakers Volkswagen (VLKAF), BMW, and Daimler (DDAIF), and chemicals giant BASF (BASFY) — made up more than one third of all European investment in those four years.

An investment deal between Beijing and Brussels was shelved last year after EU lawmakers slapped sanctions on Chinese officials over alleged human rights abuses, prompting China to retaliate with its own penalties.

The deal, agreed in principle in 2020 after years of talks, was designed to level the playing field for European companies operating in China, who have long complained that Beijing’s subsidies have put them at a disadvantage.

EU diplomats said in April that a “growing number of irritants” were hurting relations, including China’s tacit acceptance of Russia’s war in Ukraine. They have described China as “a partner for cooperation and negotiation, an economic competitor and a systemic rival.”

‘Covid carousel’

The most pressing issue for European businesses in China, according to Dunnett, is its stringent zero-Covid policy.

“For the last year, it’s been the Covid carousel, [the] Covid rollercoaster,” he said. “Every time you think [it was] about to open up, something pulls us back,” he added.

Over the weekend, thousands of protestors took to streets across China in a rare series of demonstrations against the country’s strict Covid controls. Some restrictions have since been lifted in Shanghai and other major cities.

Beijing’s uncompromising approach is helping to further dampen foreign investment in the country, especially among smaller companies, Raffaello Pantucci, a senior associate fellow at the Royal United Services Institute, a security research group, told CNN Business.

“The general business environment in China is perceived as becoming harder to navigate, and while companies still feel they have to engage given its size and potential, increasingly small to medium sized companies are giving up,” he said.

— Laura He and Sophie Jeong contributed reporting.