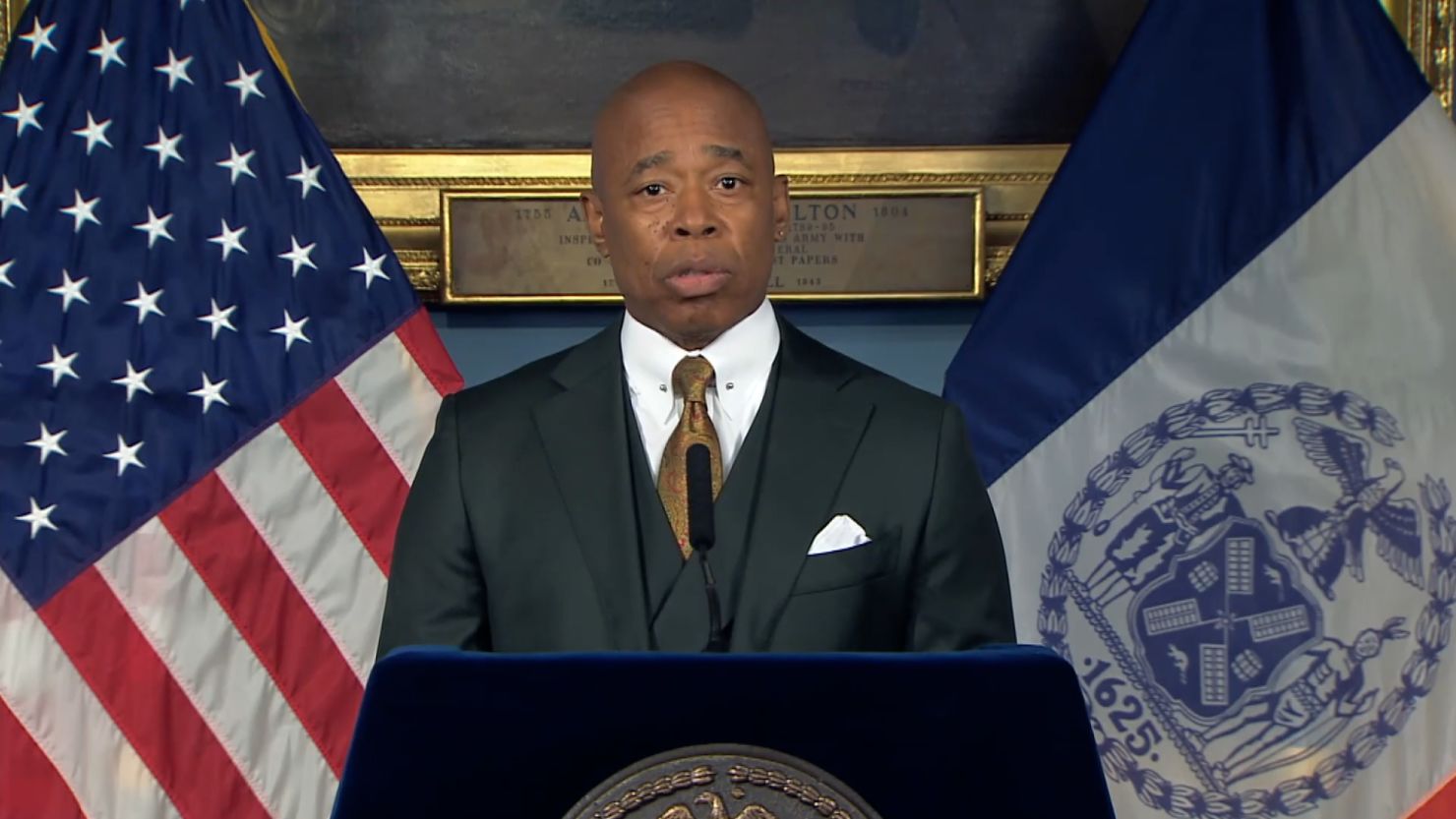

New York Mayor Eric Adams on Tuesday directed first responders to enforce a state law that allows them to potentially involuntarily commit people experiencing a mental health crisis, as part of an attempt to address concerns about homelessness and crime.

Adams said it was a myth that first responders can only involuntarily commit those who displayed an “overt act” that they may be suicidal, violent or a danger to others. Instead, he said the law allowed first responders to involuntarily commit those who cannot meet their own “basic human needs” – a lower bar.

New York Police Department officers and first responders will get additional training to help them make such evaluations and a team of mental health technicians will be available, either via a hotline or video chat, to help them determine whether a person needs to be taken to a hospital for further evaluation.

The city also plans to develop specialized intervention teams to work side by side with NYPD officers.

Adams said first responders weren’t consistently enforcing the law because they were unsure of its scope, reserving it only for cases that appeared the most serious.

“Many officers feel uneasy using this authority when they have any doubt that the person in crisis meets the criteria,” Adams said Tuesday. “The hotline will allow an officer to describe what they are seeing to a clinical professional or even use video calling to get an expert opinion on what options may be available.”

New York state enacted a law in 2021 to allow first responders to involuntarily commit a person with mental illness who is in need of immediate care.

The directive is the latest strategy aimed at getting control over a mental health crisis that Adams has identified as one of the underlying causes of violence and crime in the city.

In January, Michelle Go was pushed in front of an oncoming subway train in Times Square and killed by a man deemed to have been emotionally disturbed, according to city and NYPD officials.

In September, police arrested a mother who drowned her three children in the waters off the famed Coney Island Boardwalk and later told investigators she had dreams of them in the water, law enforcement officials told CNN.

Mental health was one of the topics discussed in October when Adams convened a two-day summit with city and state stakeholders as a way to get crime under control.

Mixed response from city advocates

The directive led to a mixed response from officials, who acknowledged the challenges of properly and humanely treating mentally ill people.

“This is a longstanding and very complex issue,” NYPD Commissioner Keechant Sewell said in a statement. “And we will continue to work closely with our many partners to ensure that everyone has access to the services they require. This deserves the full support and attention of our collective efforts.”

The NYPD said it’s in the process of aligning its policy, guidance and training to conform with the mayor’s directive.

FDNY Commissioner Laura Kavanagh in a statement said the department is “proud to partner with Mayor Adams in addressing this critical public safety issue. Our mission is simple: To be there for all New Yorkers when they need help and provide critical mental health care.”

City officials made clear the directive allows for due process, and that if a person was evaluated and deemed unfit to care for themselves, there are legal avenues they can take to fight that designation. Civil rights advocates say that is not enough.

Donna Lieberman, executive director of the New York Civil Liberties Union, in a statement called the move an “attempt to police away homelessness and sweep individuals out of sight.”

“The Mayor is playing fast and loose with the legal rights of New Yorkers and is not dedicating the resources necessary to address the mental health crises that affect our communities,” Lieberman said. “The federal and state constitutions impose strict limits on the government’s ability to detain people experiencing mental illness – limits that the Mayor’s proposed expansion is likely to violate. Forcing people into treatment is a failed strategy for connecting people to long-term treatment and care.”

New York City Public Advocate Jumaane Williams told CNN on Wednesday he supported some of the mayor’s policy but was concerned that it was short on details of how to address long-term medical issues.

“New York City residents want to be safe and want to be able to use the subway,” he said. “But if you ask them, they don’t want police to be arresting people for having a mental health crisis. They want people to get assistance and a continuum of care. The problem with this plan is it doesn’t spell out what the continuum of care is.”

Former NYPD detective Andy Bershad similarly had mixed criticism, saying he was concerned about training and potential ramifications for NYPD officers.

“Are we looking at situations potentially when a situation goes badly?” he said. “If I go to take a patient that doesn’t want to go or against their will, now I’m taking them involuntarily, what is the ramifications for the uniformed officer, EMS provider?”

CNN’s Eric Levenson contribute to this report.