The longest-running climate equipment used to measure carbon dioxide levels in the Earth’s atmosphere lost power Monday evening and is currently not recording data because of Mauna Loa’s volcanic eruption in Hawaii.

Mauna Loa, the world’s largest active volcano, erupted early Monday morning for the first time in 38 years, sending lava flows cascading down slope, impacting the road used to access the Mauna Loa Observatory.

The eruption has cut off power and access to the critical climate tool used to maintain the so-called “Keeling Curve,” which is the authoritative measurement of atmospheric carbon dioxide and vital scientific evidence for the climate crisis. The Keeling Curve graph comprises daily carbon dioxide concentration measurements taken at Mauna Loa since 1958.

The eruption has sent researchers at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California in San Diego – which established the Keeling Curve measurements at the observatory – scrambling to find an alternative location for the equipment.

Ralph Keeling, Scripps Oceanography geoscientist and son of the Keeling Curve creator, said the outlook for the future of carbon dioxide measurement from the station is now “very troubling.”

“It’s a big deal. This is the central record of the present understanding of the climate problem,” Keeling told CNN. “We probably can survive this, but it’s still a really key indicator that we hate to lose.”

The Keeling Curve has been critical at proving how much planet-warming emissions have skyrocketed above any levels experienced on the planet for at least three million years. The fact that the tool has measured the changes of carbon dioxide levels for more than 60 years virtually uninterrupted has made it the authority source on the key greenhouse gas.

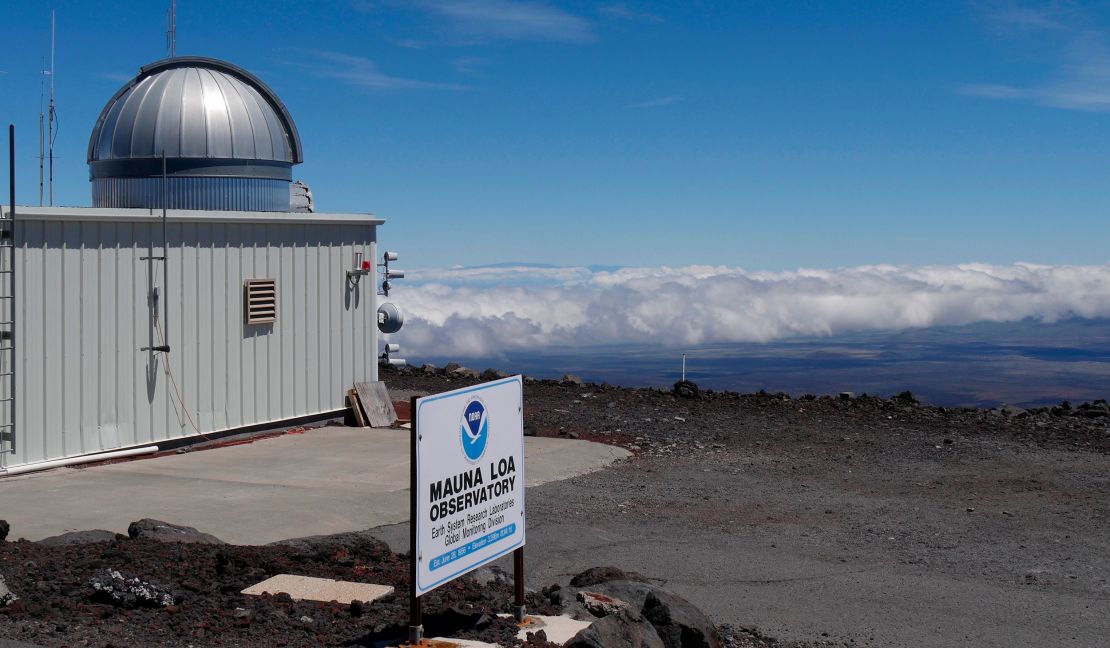

Mauna Loa has been the ideal location to measure carbon dioxide levels due to its far distance from other major land masses in Hawaii as well as the clear air and landscape of the mountaintop. The observatory is more than 11,140 feet above sea level, far away from significant pollution sources. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration also measures carbon dioxide at Mauna Loa using a different instrument.

Throughout its history there have only been a few times where the readings became unavailable: a period in 1964 due to federal budget cuts and a short period in 1984 when the last Mauna Loa eruption cut off power lines. During the latter incident, researchers had to install a generator in the observatory to resume operations.

But this time around, Keeling said the situation is “much worse” and that the timeline is unclear. “The duration of this is really hard to say, but I have a feeling we’re not going to be back to normal for months,” he said.

Researchers are racing to find a nearby substitute location free of the lava flows to get the data measurements back up and running.

“In the long run, we’ll get back up again; we’ll get back to where we were, but we’ll have a gap of some sort that may have to be filled with surrogate data,” Keeling said. “Right now, there’s no data at all. We’ve seen gaps for several months in the past, we don’t like that, so it’s really all hands on deck to try to figure out how to get something back up as soon as possible.”