On a chilly Tuesday night at London’s busy Victoria Station, a bus dropped off a group of 11 people – some wearing flip flops and without coats – and drove away.

“They were cold, hungry, stressed and disorientated,” according to homelessness charity Under One Sky, whose team spotted the group and provided assistance. The individuals had “nowhere to go” until a Home Office employee was alerted, and found the group emergency hotel accommodation.

The group was made up of asylum-seekers who had been staying at Manston migrant processing center in Kent, southern England, a facility that charities and lawmakers say has become overcrowded and descended into dire and inhumane living conditions.

According to the Home Office, officials were under the impression that the 11 individuals had accommodation arranged in London. London Mayor Sadiq Khan said it was “shameful” they were abandoned in the center of the city, calling it “a complete failure of duty and leadership.”

But the incident is emblematic of Britain’s dramatically overwhelmed system for dealing with asylum-seekers and illegal migrants.

The number of asylum claims processed in the UK has collapsed in recent years, leaving people in limbo for months and years – trapped in processing facilities or temporary hotels and unable to work – and fueling an intractable debate about Britain’s borders.

“The system is broken,” Britain’s Home Secretary Suella Braverman told Parliament on Monday – an inarguable but jarring admission after 12 years of Conservative rule, which has seen an unending line of ministers promising and failing to clamp down on illegal migration.

Braverman blamed a rapid increase in small boat crossings across the English Channel, organized by people smugglers on mainland Europe. The beleaguered minister described the crossings in highly charged terms as an “invasion” of Britain’s south coast. “Let’s stop pretending that they are all refugees in distress,” she said.

But the chaos facing migrants and asylum-seekers in the UK is also the result of a decade of political choices, with funding and action failing to match the heavy-handed rhetoric espoused by successive Conservative governments.

“It’s shambolic and it’s cruel,” Ben Ramanauskas, a research economist at Oxford University and an adviser to Liz Truss while the previous prime minister was secretary of state for international trade, told CNN about the country’s system to deal with asylum-seekers.

“Part of that is due to the culture set by the Home Office, which views most immigrants with suspicion and treats them like potential criminals,” Ramanauskas said. “It’s a deeply unfair and unjust system.”

The Home Office did not respond directly to that charge when approached by CNN, but said in a statement: “The number of people arriving in the UK who require accommodation has reached record levels and has put our asylum system under incredible strain.”

Small boat crossings rise

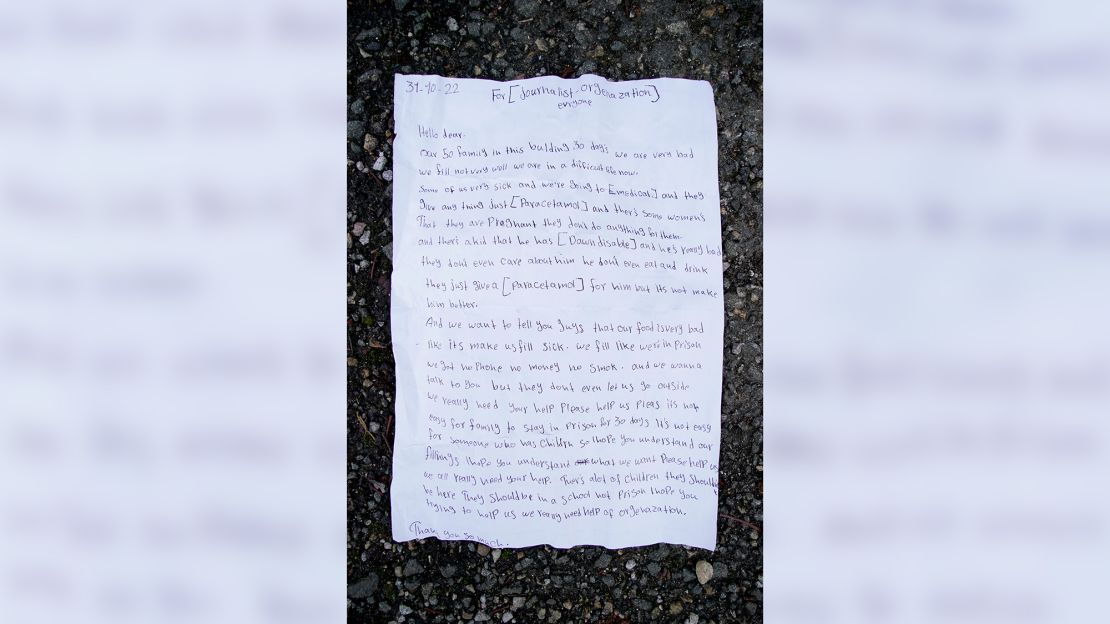

Another striking glimpse into the lives of migrants within Britain’s processing facilities came flying over the fence from within the Manston facility this week.

“We are in a difficult life now … we fill like we’re in prison (sic),” read a letter, apparently written by a young girl and stuffed inside a bottle that was then thrown towards assembled journalists.

“Some of us very sick … ther’s some women’s that are pregnant they don’t do anything for them (sic) … We really need your help. Please help us,” the letter reads.

The situation at the asylum-processing center is a “breach of humane conditions,” Conservative lawmaker Roger Gale told Sky News Monday, as dozens of charities wrote to the prime minister to raise concerns over “overcrowding.”

The facility is currently holding around 4,000 people, among them women and children, despite being intended to only hold 1,500, Gale said. Immigration Minister Robert Jenrick later told Sky News that some people at the center were “sleeping on the floor.”

He claimed the “root cause of what we’re seeing at Manston is not the government,” but the growing number of migrants traveling across the Channel onto England’s shores.

Those numbers have shot up in recent years. 38,000 people have arrived in the UK by small boat this year, up from 28,000 last year and less than 2,000 in 2019, according to Home Office data.

The crossings are a relatively new phenomenon, which emerged after thousands of migrants hoping to cross into England spent months and years in the so-called Calais “jungle,” a sprawling settlement on the northern coast of France guarded by French and British border officers.

“In late 2018, a couple of boats successfully navigated the channel,” giving rise to a small “cottage industry” of smugglers, Rob McNeil, the deputy director of the Migration Observatory, told CNN.

“Not only did it work, but because it was a very visible spectacle it became very prominent in the British public discourse. It was front page news,” he said. “And so it became visible to other people that this was a successful technique.

“Instead of having a bottleneck at Calais, you suddenly had a showerhead (with) multiple little nozzles across the French coast” from which people could launch dangerous journeys in dinghies and small vessels, McNeil said. “That’s much harder to police.”

The number of arrivals in the UK remains relatively low compared to EU member states; last year Britain ranked fourth in total asylum applications and 19th in per capita claims among European countries, according to the Migration Observatory.

But while the government has pointed the finger at increased crossings for overrunning the country’s asylum network, it has done little to reduce their impact on the UK – and a litany of ministerial decisions have made disruption worse for Britons and migrants alike.

The speed at which asylum claims are processed has slumped remarkably in recent years. 87% of claims received an initial decision within six months in the second quarter of 2014, according to the Migration Observatory, but seven years later that figure was just 6%. The fall comes after the government scrapped its six-month target in mid-2019.

It means migrants are being housed in temporary accommodation and hotels while waiting to hear news on their claim, a policy at which Braverman has repeatedly lashed out. A Home Office spokesperson told CNN there are currently more than 37,000 asylum-seekers in hotels, costing the UK taxpayer £5.6 million ($6.35 millon) a day.

Many migration experts point the finger for that bill squarely back at the government.

“The Home Office has clearly made decisions about allocation of resources which have impacted on processing speeds,” McNeil said.

“If (asylum-seekers’) claims were processed more quickly and more efficiently, then the system would not be snarled up in the way that it is and the human experience of these people would be less unpleasant, while at the same time the costs to the taxpayer would be considerably lower,” he added.

“This issue has not benefited anybody. It is important this asylum backlog is addressed as a matter of some urgency, if the government wants to take charge of the situation.”

Search for solutions

To date, the government’s policy – a deal to deport some migrants to Rwanda – has been bogged down in legal appeals and failed to transport a single person in the seven months since it was announced.

“It clearly isn’t working (and) it hasn’t acted as a deterrent in any way” to other asylum-seekers, Ramanauskas said.

Surrounding the Rwanda plan has been a continued swirl of provocative language on illegal migration, which the government argues underpins a strong stance but critics say is divisive and cruel towards those escaping war, instability or persecution.

“What the government has done through its rhetoric over the past years is try to merge in people’s minds asylum seekers and illegal immigrants,” as part of a “quite conscious attempt to suggest all asylum seekers are inherently illegal,” Tim Bale, a professor of politics at Queen Mary University in London, and the author of books on the Conservative Party, told CNN.

But there are at least partial solutions to the UK’s seemingly intractable illegal migration crisis, experts believe.

As well as prioritizing the processing of claims by boosting funding and creating new centers around the country, Britain could ditch a rule that asylum applications must be made on UK soil – allowing people to apply at embassies before they complete a lengthy journey through Europe and across the Channel.

And a current rule that bars asylum-seekers from working for one year should be loosened to help people provide for themselves and contribute to the economy, critics say.

“It’s madness: You’re keeping people in poverty, which leads to crime – they don’t have anything to do to spend their time, which is not good for them and bad for local communities,” Ramanauskas said. Sweden, Canada and Australia are among countries that allow asylum-seekers to work immediately, while in the United States, the wait is six months.

A political trade-off

For all of the heavy-handed rhetoric of successive Conservative governments, a political calculation is also at play.

“It’s never done the Conservative Party any harm, since the beginning of the 1960s, to have immigration on people’s minds,” Bale said.

During its 12 years in power – a period largely dominated by Brexit and claims by its supporters that the UK could “take back control” of its borders – the Conservatives have repeatedly sought to paint the opposition Labour Party as “remainers” who would be soft on migration.

That imperative means solving Britain’s illegal migration conundrum may not yield the political dividends the party is looking for – particularly as it struggles to get a handle on Britain’s economic crisis. “If you can’t deliver to people in their pocket, then this is a useful distraction,” Bale said.

Still, even on traditionally fruitful domain, it remains increasingly possible the Conservative Party will run out of road. “There’s always a trade-off between it being in the news and voters beginning to think the government’s lost control,” Bale said.

Opinion polls suggest voters are losing faith in the Conservatives to tackle the issue of immigration – a trend which, in the past, has left the party battling to fend off criticism from insurgent right-wing parties that it hasn’t done enough to reduce arrivals.

That’s the dynamic facing Rishi Sunak, Britain’s new Prime Minister, who has readily embraced the Rwanda plan and spent much of his early political capital defending his Home Secretary, Braverman, as she decries the UK’s “broken” asylum system.

After 12 years of harsh words, and as the human impact on asylum-seekers in Britain begins to seep out of facilities like Manston, Sunak risks quickly losing the trust of Britons on all sides of the migration debate.

“You have got to the point where people are entitled to ask … if it is broken, who broke it?” Bale said.