President Joe Biden is in a bind.

He has no choice but to talk about the economy in the home stretch of the midterm elections – it’s the issue, given near 40-year high inflation and high gas prices, that worries voters most.

But by doing so, he’s drawing attention to his own and Democrats’ biggest liability – their failure to fix things already and accusations that they made it worse.

There’s no terrain on which Republicans would rather fight as they stage a referendum on Biden’s presidency and try to inflict the traditional first-term curse on a new White House by winning back the House and possibly the Senate.

Democrats had hoped that issues like the Supreme Court’s overturning of the nationwide right to an abortion and ex-President Donald Trump’s undiminished threat to democracy would blunt the GOP advantage on the economy by November. But the latest polling suggests that while those issues do concern millions of voters, their potency as vote-movers pales in comparison with the high cost of living.

Biden is answering this challenge by seeking to change perceptions among Americans about the state of the economy. He’s highlighting undeniable areas of progress and economic strength, and making a broader argument that his policies on energy, drugs and infrastructure will, over time, lift up working Americans.

And he’s lashing out at Republicans’ record on the economy – a fair point since the last two GOP presidents have presided over economic busts, leaving their Democratic successors to pick up the pieces.

“Democrats are building a better America for everyone with an economy that grows from the bottom up and the middle out, where everyone does well,” Biden said in a speech on Monday.

Latest election news

“Republicans are doubling down on their mega-MAGA, trickle-down economics that benefits the very wealthy, failed the country before and will fail it again if they win. Democrats are lowering your everyday costs like prescription drugs, health care premiums, energy bills and gas prices.”

Biden’s speech was notable not just for its content, but its venue. He was holding forth at the headquarters of the Democratic National Committee in Washington rather than at a big rally for some endangered Democrat in a critical suburban district that could decide the election. His comparatively slim campaign travel schedule reflects the liabilities faced by a President with underwater approval ratings in troublesome economic times.

The question at the center of the midterms

Back in January, Laura Godinez told CNN’s Maeve Reston in Reno, Nevada, as she lifted groceries into a truck that cost $145 to fuel, that she felt she was financially better off under former President Donald Trump.

Nine months of turbulent politics and unpredictable global events later, her words might still define the election. The perennial question over whether voters are better off now than they were when the other party was in power is one Biden is trying his hardest to answer by pitching it forward, as he seeks to build a more equitable economy.

But two new CNN/SSRS polls released Monday showing close Senate races in swing states Pennsylvania and Wisconsin encapsulated the President’s challenge and explain the dynamics of the midterm contest exactly two weeks out from Election Day.

The surveys show that the economy is by far the most important issue to voters. In Wisconsin, 47% said that the economy and inflation were the top issue as they consider their vote. In Pennsylvania, the equivalent figure was 44%. This is more than double the percentage of voters (19%) who said abortion was their decisive concern in each state. The polls also suggest that Biden is an imperfect economic messenger. His approval rating is only 43% in Wisconsin and 45% in the Keystone state, below the levels where he could be a true electoral asset.

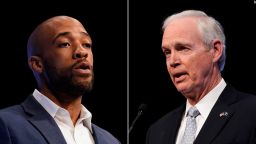

There are also signs that the economy could damage individual Democratic candidates. Voters who say the economy is their top issue in Wisconsin back Republican Sen. Ron Johnson 78% to 21% over his Democratic challenger, Lt. Gov. Mandela Barnes. In Pennsylvania, Republican Senate nominee Mehmet Oz doubles Democratic Lt. Gov. John Fetterman’s support in a similar cohort by 64% to 32%.

Still, the fact that these races, which represent Democrats’ best opportunities to pad their Senate majority, remain close shows that there may be other factors at play. Even if the economy is a driving concern of voters, issues related to candidate quality or the fact that the United States is a nation split down the middle politically could also weigh on the election result. That should give the President hope at least.

Biden strives for an economic contrast

But Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders, an independent who lost out to Biden in the last Democratic presidential primary, warned Sunday that Democrats need to go on the attack on the economy.

“I think what we have got to do is contrast what a strong pro-worker Democratic position is, with the corporate agenda of the Republicans,” Sanders told CNN’s Jake Tapper on “State of the Union.”

“It’s important to take the attack to the Republicans. What do they want to do other than complain?” he said.

Sanders had a point. The Republican message has been far more about highlighting the economic struggles of everyday Americans and Biden’s faults than presenting a policy-rich alternative. But that is also the luxury of being in the opposition. Biden has been hitting the kind of notes that Sanders wants to hear in recent weeks. And his vision for an economy that benefits working Americans over the wealthy was the core of his 2020 campaign.

Two years on, his economic closing argument may not turn around the direction of the campaign in the final days but could, if it sticks, at least slow some Republican momentum in recent polls.

Yet Biden’s facing an uphill task because he is being forced to defend his own record, without Trump as a foil on the ballot, even if many of his endorsed GOP candidates are.

While voters tend to give presidents too much blame for economic blight and too much credit for booms, Biden’s the one in the Oval Office so the buck stops with him.

And when voters have seen prices for staples like eggs, meat, and milk shoot up over the last year and have spent months draining their wallets to fill their cars, it’s hard to get their attention on a more theoretical economic argument.

The President may well be correct that his legislative successes in Congress on cutting the price of some prescription drugs for seniors, building a clean energy economy and creating more manufacturing jobs will create more long-term prosperity. But such long-term benefits are not felt as immediately as sticker shock at the grocery store. Any time a President is making an argument about the economy that involves painting a rosier picture than people perceive in their own lives, they are in trouble. And although Biden frequently highlights the historically low unemployment rate, inflation is outstripping a sense of security Americans have about the job market. And it cancels out the impact of any slight wage growth.

Biden also faces a credibility gap. For months, the White House told Americans that inflation was a temporary phenomenon and a “transitory” after-effect of the pandemic. Now, voters have a right to ask why the White House and the Federal Reserve underestimated the threat. Post-mortems of the pandemic recovery will examine whether Biden’s big spending social and infrastructure plans and the Federal Reserve’s policies created a situation where too much money in the economy was chasing too few goods at a time of supply chain crunches and triggered or substantially worsened the inflation crisis.

Claims by Biden and Democrats that the entire developed world is battling rising inflation and that the US has it better than others might be true. But that’s not much consolation to an American driver struggling to fill their gas tank.

The same dynamic played out when the President slammed rising gasoline costs as “Putin’s price hike.” Pointing out that the war in Ukraine was to blame for high oil prices or slamming Middle Eastern producers for not pumping more crude allows the President to vent about a problem over which he doesn’t have much control. But it doesn’t noticeably ease the burden on consumers.

Some strategists also wonder whether the President erred by making such a big deal of a summer slump in gasoline prices that, together with the Supreme Court’s decision on abortion and a good run in Congress, spiked Democratic fortunes for a few months. When prices headed back up again, the President was put on the defensive, even if the price per gallon nationally is about 10 cents cheaper than it was a week ago.

The President is also resorting to scare tactics, warning that a new Republican Congress would demand deep cuts to social programs in return for raising the federal debt ceiling in a fiscal showdown likely to take place in the first year of the new Congress.

“Republicans are determined to hold the economy hostage, either give into their demands on Social Security and Medicare, which millions of Americans rely on and earn and pay for … or Republicans are going to crash the economy,” Biden said Monday.

The President also contrasted his record on trimming the deficit with Trump’s and criticized the former President’s $2 trillion tax cut, which mostly benefited the wealthy and corporations.

Again, these arguments are often logical and rooted in fact. And they might be more resonant in a better economic environment. But high gasoline and grocery prices are so visceral they create an emotional response among voters struggling to make ends meet. If Republicans win the House and Senate next month, that will probably be the reason why.