Erin Hanson has spent years developing the vibrant color palette and chunky brushstrokes that define the vivid oil paintings for which she is known. But during a recent interview with her, I showed Hanson my attempts to recreate her style with just a few keystrokes.

Using Stable Diffusion, a popular and publicly available open-source AI image generation tool, I had plugged in a series of prompts to create images in the style of some of her paintings of California poppies on an ocean cliff and a field of lupin.

“That one with the purple flowers and the sunset,” she said via Zoom, peering at one of my attempts, “definitely looks like one of my paintings, you know?”

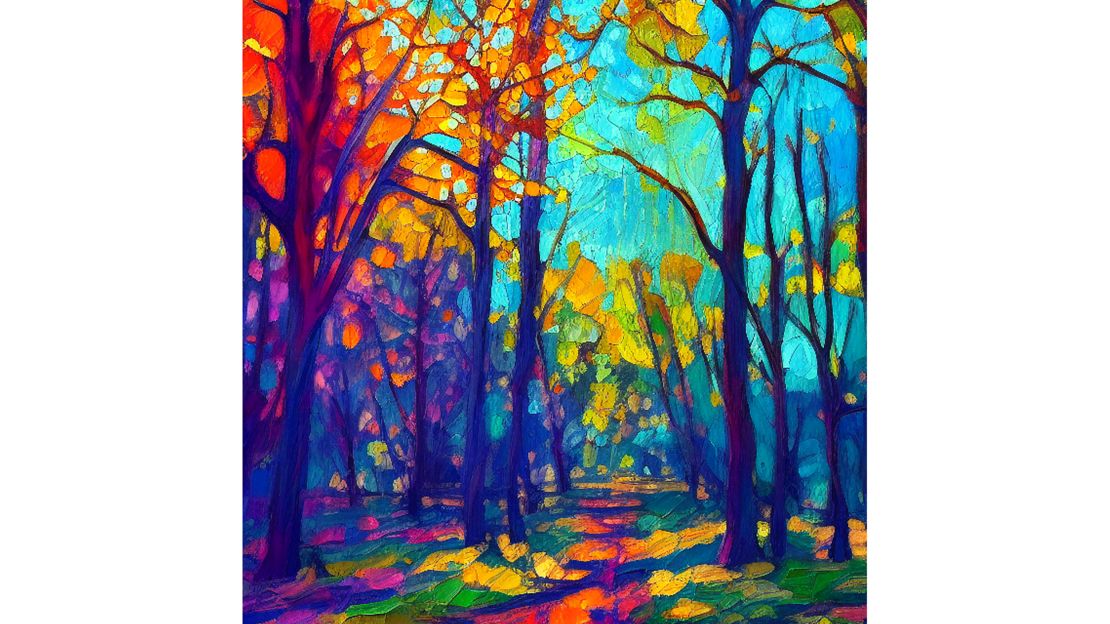

With Hanson’s guidance, I then tailored another detailed prompt: “Oil painting of crystal light, in the style of Erin Hanson, light and shadows, backlit trees, strong outlines, stained glass, modern impressionist, award-winning, trending on ArtStation, vivid, high-definition, high-resolution.” I fed the prompt to Stable Diffusion; within seconds it produced three images.

“Oh, wow,” she said as we pored over the results, pointing out how similar the trees in one image looked to the ones in her 2021 painting “Crystalline Maples.” “I would put that on my wall,” she soon added.

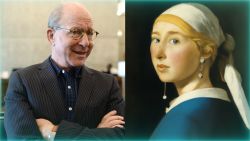

Hanson, who’s based in McMinnville, Oregon, is one of many professional artists whose work was included in the data set used to train Stable Diffusion, which was released in August by London-based Stability AI. She’s one of several artists interviewed by CNN Business who were unhappy to learn that pictures of their work were used without someone informing them, asking for consent, or paying for their use.

Once available only to a select group of tech insiders, text-to-image AI systems are becoming increasingly popular and powerful. These systems include Stable Diffusion, from a company that recently raised more than $100 million in funding, and DALL-E, from a company that has raised $1 billion to date.

These tools, which typically offer some free credits before charging, can create all kinds of images with just a few words, including those that are clearly evocative of the works of many, many artists (if not seemingly created by the same artist). Users can invoke those artists with words such as “in the style of” or “by” along with a specific name. And the current uses for these tools can range from personal amusement to more commercial cases.

In just months, millions of people have flocked to text-to-image AI systems and they are already being used to create experimental films, magazine covers and images to illustrate news stories. An image generated with an AI system called Midjourney recently won an art competition at the Colorado State Fair, and caused an uproar among artists.

But as artists like Hanson have discovered that their work is being used to train AI, it raises an even more fundamental concern: that their own art is effectively being used to train a computer program that could one day cut into their livelihoods. Anyone who generates images with systems such as Stable Diffusion or DALL-E can then sell them (the specific terms regarding copyright and ownership of these images varies).

“I don’t want to participate at all in the machine that’s going to cheapen what I do,” said Daniel Danger, an illustrator and print maker who learned a number of his works were used to train Stable Diffusion.

When fine art becomes data

The machines are far from magic. For one of these systems to ingest your words and spit out an image, it must be trained on mountains of data, which may include billions of images scraped from the internet, paired with written descriptions.

Some services, including OpenAI’s DALL-E system, don’t disclose the datasets behind their AI systems. But with Stable Diffusion, Stability AI is clear about its origins. Its core dataset was trained on image and text pairs that were curated for their looks from an even more massive cache of images and text from the internet. The full-size dataset, known as LAION-5B was created by the German AI nonprofit LAION, which stands for “large-scale artificial intelligence open network.”

This practice of scraping images or other content from the internet for dataset training isn’t new, and traditionally falls under what’s known as “fair use” — the legal principle in US copyright law that allows for the use of copyright-protected work in some situations. That’s because those images, many of which may be copyrighted, are being used in a very different way, such as for training a computer to identify cats.

But datasets are getting larger and larger, and training ever-more-powerful AI systems, including, recently, these generative ones that anyone can use to make remarkable looking images in an instant.

A few tools let anyone search through the LAION-5B dataset, and a growing number of professional artists are discovering their work is part of it. One of these search tools, built by writer and technologist Andy Baio and programmer Simon Willison, stands out. While it can only be used to search a small fraction of Stable Diffusion’s training data (more than 12 million images), its creators analyzed the art imagery within it and determined that, of the top 25 artists whose work was represented, Hanson was one of just three who is still alive. They found 3,854 images of her art included in just their small sampling.

Stability AI founder and CEO Emad Mostaque told CNN Business via email that art is a tiny fraction of the LAION training data behind Stable Diffusion. “Art makes up much less than 0.1% of the dataset and is only created when deliberately called by the user,” he said.

But that’s slim comfort to some artists.

Angry artists

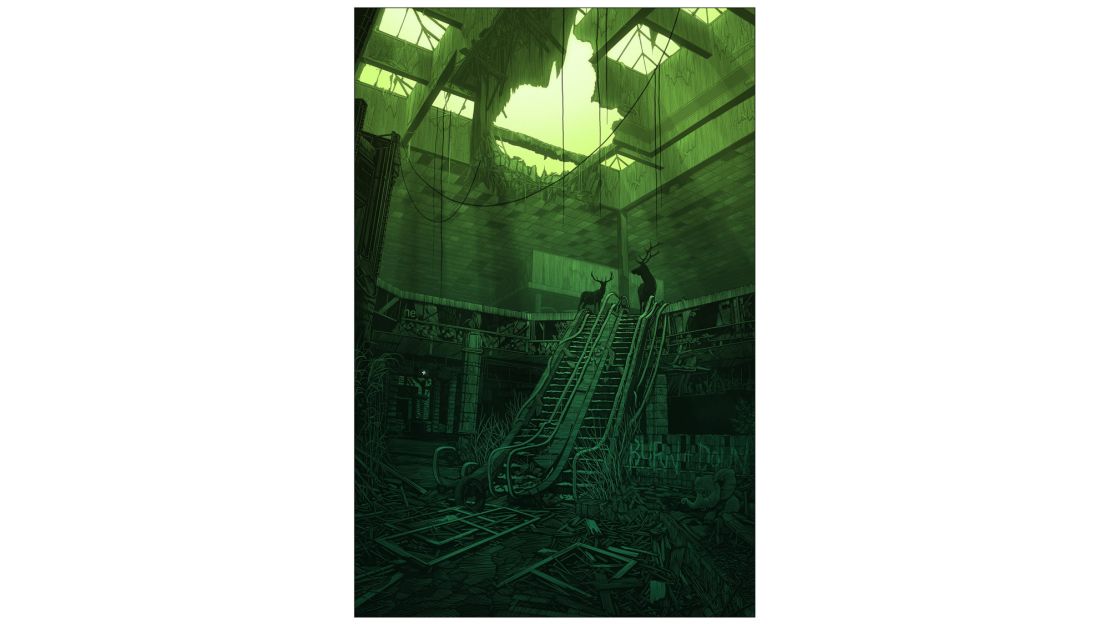

Danger, whose artwork includes posters for bands like Phish and Primus, is one of several professional artists who told CNN Business they worry that AI image generators could threaten their livelihoods.

He is concerned that the images people produce with AI image generators could replace some of his more “utilitarian” work, which includes media like book covers and illustrations for articles published online.

“Why are we going to pay an artist $1,000 when we can have 1,000 [images] to pick from for free?” he asked. “People are cheap.”

Tara McPherson, a Pittsburgh-based artist whose work is featured on toys, clothing and in films such as the Oscar-winning “Juno,” is also concerned about the possibility of losing out on some work to AI. She feels disappointed and “taken advantage of” for having her work included in the dataset behind Stable Diffusion without her knowledge, she said.

“How easy is this going to be? How elegant is this art going to become?,” she asked. “Right now it’s a little wonky sometimes but this is just getting started.”

While the concerns are real, the recourse is unclear. Even if AI-generated images have a widespread impact — such as by changing business models — it doesn’t necessarily mean they’re violating artists’ copyrights, according to Zahr Said, a law professor at the University of Washington. And it would be prohibitive to license every single image in a dataset before using it, she said.

“You can actually feel really sympathetic for artistic communities and want to support them and also be like, there’s no way,” she said. “If we did that, it would essentially be saying machine learning is impossible.”

McPherson and Danger mused about the possibility of putting watermarks on their work when posting it online to safeguard the images (or at least make them look less appealing). But McPherson said when she’s seen artist friends put watermarks across their images online it “ruins the art, and the joy of people looking at it and finding inspiration in it.”

If he could, Danger said he would remove his images from datasets used to train AI systems. But removing pictures of an artist’s work from a dataset wouldn’t stop Stable Diffusion from being able to generate images in that artist’s style.

For starters, the AI model has already been trained. But also, as Mostaque said, specific artistic styles could still be called on by users because of OpenAI’s CLIP model, which was used to train Stable Diffusion to understand connections between words and images.

Christoph Schuhmann, an LAION founder, said via email that his group thinks that truly enabling opting in and out of datasets will only work if all parts of AI models — of which there can be many — respect those choices.

“A unilateral approach to consent handling will not suffice in the AI world; we need a cross-industry system to handle that,” he said.

Offering artists more control

Partners Mathew Dryhurst and Holly Herndon, Berlin-based artists experimenting with AI in their collaborative work, are working to tackle these challenges. Together with two other collaborators, they have launched Spawning, making tools for artists that they hope will let them better understand and control how their online art is used in datasets.

In September, Spawning released a search engine that can comb through the LAION-5B dataset, haveibeentrained.com, and in the coming weeks it intends to offer a way for people to opt out or in to datasets used for training. Over the past month or so, Dryhurst said, he’s been meeting with organizations training large AI models. He wants to get them to agree that if Spawning gathers lists of works from artists who don’t want to be included, they’ll honor those requests.

Dryhurst said Spawning’s goal is to make it clear that consensual data collection benefits everyone. And Mostaque agrees that people should be able to opt out. He told CNN Business that Stability AI is working with numerous groups on ways to “enable more control of database contents by the community” in the future. In a Twitter thread in September, he said Stability is open to contributing to ways that people can opt out of datasets, “such as by supporting Herndon’s work on this with many other projects to come.”

“I personally understand the emotions around this as the systems become intelligent enough to understand styles,” he said in an email to CNN Business.

Schuhmann said LAION is also working with “various groups” to figure out how to let people opt in or out of including their images in training text-to-image AI models. “We take the feelings and concerns of artists very seriously,” Schuhmann said.

Hanson, for her part, has no problem with her art being used for training AI, but she wants to be paid. If images are sold that were made with the AI systems trained on their work, artists need to be compensated, she said — even if it’s “fractions of pennies.”

This could be on the horizon. Mostaque said Stability AI is looking into how “creatives can be rewarded from their work,” particularly as Stability AI itself releases AI models, rather than using those built by others. The company will soon announce a plan to get community feedback on “practical ways” to do this, he said.

Theoretically, I may eventually owe Hanson some money. I’ve run that same “crystal light” prompt on Stable Diffusion many times since we devised it, so many in fact that my laptop is littered with trees in various hues, rainbows of sunlight shining through their branches onto the ground below. It’s almost like having my own bespoke Hanson gallery.