Gabriel Burks, like most Black people in Georgia, nearly always votes for Democrats. But this November, he’ll be voting for Republican Gov. Brian Kemp.

“Kemp hasn’t done nothing wrong as a governor,” the 49-year-old dad told CNN at the Georgia National Fair last week as he watched his son go down a slide about 100 yards from Kemp’s campaign bus at the fairgrounds. “He opened up. I got nothing against him.”

But that’s where the otherwise loyal Democrat expects his Republican support to end this year – he also plans to vote for Sen. Raphael Warnock over his Republican rival, Herschel Walker.

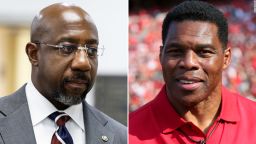

Evidence suggests that Burks is far from alone and that there are more ticket-splitters going for Kemp and Warnock than might be expected in this age of deep partisanship. A new Quinnipiac poll out this week found Kemp with 50% support compared to 49% for his Democratic opponent, Stacey Abrams. But Warnock leads Walker in the same poll, 52% to 45%.

Latest election news

Republicans and Democrats alike in Georgia say the Kemp-Warnock voter phenomenon is real and crucial for understanding how to win in a state where recent statewide elections have been decided by narrow margins.

“There’s some,” admitted Rep. Sanford Bishop, a Democratic congressman from southwest Georgia, when asked if he knows voters in his district who are willing to cross the aisle and vote for Kemp. “They just think he’s done a good job.”

The existence of Kemp-Warnock voters reflect how, as Georgia has become narrowly divided on politics, the path to victory in the state may include appealing to the small but crucial number of swing voters here. Kemp remains an unabashed conservative, but has nonetheless established his independence from his party by refusing to agree to former President Donald Trump’s demands that he overturn the 2020 election results in the Peach State. And despite Warnock’s progressive inclinations, the new senator has fashioned himself as a problem-solver willing to work with Republicans.

“I have good relationships with my colleagues on both sides of the aisle, and I like to think that even those who don’t always agree with me respect me,” Warnock told reporters following a rally in Columbus last week. “And I think that’s important for the process of getting things done.”

If Georgia defies the odds in what could be a good Republican year and delivers a split decision in its two marquee statewide races, the lesson of appealing to the state’s swing voters may extend into 2024 as both Republicans and Democrats look to Georgia as one of the most important battleground states.

Even as they come from opposing ends of the ideological spectrum, Kemp and Warnock are targeting White college-educated and minority working-class Georgians that are now up for grabs for both parties.

These swing voters generally fall into two camps: minority Democratic-leaning men who prefer Kemp to Abrams – like Burks – and White suburban Republican leaners for whom voting for Walker is a bridge too far.

At the fair in Perry, Burks was pleasantly surprised to learn that Kemp was on the grounds campaigning. He said his vote was not a vote against Abrams, who narrowly lost to Kemp in 2018, but that it was important to him that Kemp quickly reopened the state following a brief shutdown during the pandemic.

“I’m with him on the gun law, too,” Burks added, referring to a law Kemp signed earlier this year allowing most Georgians to legally carry a concealed handgun without a license.

And like so many Georgians, Burks has been paying attention to the daily soap opera surrounding Walker, including the recent allegations that the former Georgia football star paid for a girlfriend to get an abortion in 2009 and asked her to get another one two years later. (Walker, who has opposed abortion rights throughout his campaign, has denied this and CNN has not independently verified the allegations.)

“I don’t like Herschel,” Burks said. “Something’s wrong with him.”

It’s a common refrain among swing voters in Georgia. They praise Kemp for his accomplishments in his first term of office but express disgust or concern about Walker. The recent allegations are only the latest of Walker’s woes. Warnock and his allies have spent millions in TV and digital ads highlighting Walker’s past violent threats toward women, in particular his ex-wife, and that narrative is inescapable.

One young mother at a park in Alpharetta, who told CNN she hasn’t decided who she will vote for, lamented that she sees the ads all the time when she loads up videos on YouTube to calm her infant daughter. But the anti-Walker ads are working. Her husband told CNN that while he’s voting for Kemp, he hasn’t decided if he’ll vote for Warnock – he only knows he just can’t go for Walker.

“I just won’t vote for Herschel. We need someone who can do more than just fog up a mirror,” he said.

‘That’s always been the problem for Herschel’

Despite a favorable environment for the GOP, Georgia Republicans are now scrambling to claw back some of their own Kemp-Warnock voters in the final weeks ahead of Election Day. Georgians First, a political action committee supporting Kemp’s reelection, is spending millions on a final get-out-the-vote door-knocking effort in the suburbs around Atlanta. The group will target identified GOP-leaning voters who the party fears are less motivated to get to the polls this year, in part because of Walker’s shortcomings.

“That’s always been the problem for Herschel. A lot of the people who he’s underperforming with are Republicans,” said one GOP operative familiar with the plans.

The scripts and literature will not directly mention Walker or Warnock, this person said, but will instead “remind Republicans that they are Republicans” and encourage them to support the entire ticket on November 8. While the Kemp campaign is expressing confidence they can defeat Abrams on Election Day, Republicans want to ensure that the Senate race does not go to a runoff, which would happen if neither Walker nor Warnock gets a majority.

And some in the party say they hope Friday’s debate in Savannah between the two Senate candidates can help Walker reassert control over his campaign’s narrative and calm down wavering voters.

“Talking to other Republicans, many are dubious that the Kemp-Warnock bloc is a lot of people,” said Brian Robinson, a veteran GOP strategist in Georgia. “But we know there’s a group out there that needs convincing. A strong debate could reassure Republican leaners.”

If Walker pulls out a win, either in November or in a runoff that would be scheduled for December, he can thank Kemp for keeping the GOP’s chances afloat in Georgia.

Democrats have long viewed Georgia as a ripe target, with Abrams’ close loss to Kemp in 2018 as the first indication Republican hegemony was in trouble. That was followed by a banner cycle for Democrats in 2020, when Joe Biden edged out Trump in the state and, in both runoff elections two months later, Warnock and his fellow Democrat Jon Ossoff won both of Georgia’s Senate seats and flipped party control of the chamber.

But since taking office, Kemp has helped guide the Republican ship in Georgia. While pursuing a conservative agenda – restricting abortion access, cutting taxes and loosening gun laws – Kemp has also earned some independent credibility after his high-profile refusal to agree to Trump’s demands that he help overturn the 2020 presidential election results in Georgia.

Kemp, for his part, has been reaching out to Black voters, despite polls showing the vast majority will vote for Abrams. Last week, he was the only Republican candidate to attend a forum in Atlanta put on by a consortium of Black-listener radio stations.

“I thought it was a great opportunity to talk about my record,” Kemp told CNN when asked about the appearance. “We’re not taking any vote for granted. We’re asking for every vote that’s out there.”

Some in Atlanta’s influential Black business community are taking notice, too. One prominent Black businessman, who requested anonymity to talk candidly about his vote, told CNN that he’s met with all four of the major candidates in the governor and Senate races. He says he’s voting for Kemp and Warnock because he feels confident both are delivering economically for Georgia.

“At the end of the day, I feel like, I’m for anybody that’s for economics and businesses thriving,” the businessman said.

Abrams has tried to build on her 2018 coalition of minorities, college-educated urban liberals, and suburbanites turned off by Trump’s GOP, and her campaign’s focus remains primarily on organizing the massive turnout operation that helped win the state for Biden. But her struggle to replicate her near-success from four years earlier is as much about Kemp’s own ability to make a case that his tenure has made Georgians better off – and that Abrams would disrupt Georgia’s above-average economic outlook. Even some Black voters say Abrams has embraced an agenda that’s too progressive, too reliant on government and too burdensome on business.

“I vote for what makes sense, and some of the things that Stacey is proposing, I don’t necessarily align with,” said the businessman.

‘I’m focused on who I’m working for’

Whereas Kemp is relying on his record to pitch himself to swing voters, Warnock is trying to push back against the anti-Democratic national mood and present himself as different from Biden and the Democratic Party in Washington.

And whereas Abrams is trying to create a new, urban-suburban coalition for Democrats in Georgia, Warnock is instead looking to win in Georgia as it currently is. That means at least trying to win over Republican leaners, even in the most conservative rural pockets of the state. So far this year, according to a campaign official, Warnock has made dozens of campaign stops in rural and exurban areas – from Valdosta in the southernmost part of the state to the foothills of the Appalachians in north Georgia.

“Both Kemp and Warnock are in the persuasion world,” said one Republican operative.

On the trail, Warnock frequently mentions his collaboration with Republican senators in order to achieve what he says are good things for Georgians.

“I’m not focused on who I’m working with,” he said at a rally in Macon last week. “I’m focused on who I’m working for.”

In one popular TV ad targeting the agriculture vote, Warnock stands in a large container as peanuts fall down from a silo above. Interspersed with a testimonial from a White farmer in south Georgia, Warnock mentions his work with Sen. Tommy Tuberville, an Alabama Republican, to help reduce trade barriers for exporting peanuts.

Warnock is not shy about talking up Democratic agenda items, particularly in front of a receptive crowd of like-minded voters. But on the trail, he allows surrogates and supporters to make the direct case against Walker, which comes alongside the millions of dollars in TV and digital ads he and allied groups are spending to depress would-be Walker voters.

In fact, Warnock simply calls Walker “my opponent” and avoids even mentioning his name – an acknowledgment, perhaps, that the former football star for the Georgia Bulldogs remains a popular figure outside of politics. And as for the recent allegations, Warnock has declined to engage directly with the claim that Walker paid for an abortion.

More on key Senate races

Instead, Warnock has used questions about the news to pivot to going after Walker’s position on abortion as extreme and out-of-touch. Walker said in May that he supports a full ban on abortions, with no exceptions.

“We do know that my opponent has trouble with the truth,” Warnock told reporters in Columbus. “And we’ll see how all this plays out, but I am focused squarely on the health-care needs of my constituents, including reproductive health care.”

The carefully worded response reflects the delicate situation Warnock finds himself in during what should be a good Republican year. While Walker’s troubles have damaged him with some GOP voters, some Democrats in Georgia are concerned that pushing too hard on the issue could have the unintended consequence of making Walker into a political victim and solidifying the soft support he has within his party.

But Warnock’s small lead in the Quinnipiac poll, which was conducted after the allegations about the Republican came to light, suggests Walker’s problem getting enough Georgia Republican voters on board persists. Bill Kecskes, a Republican from Carrollton, told CNN he will support Kemp but is considering voting for Warnock, especially after the latest allegations about Walker.

“If he would just own up to them, not telling the truth, that’s not good,” Kecskes said. “It’s a double standard. Anybody else would have been run out of town on a rail.”

CNN’s Eva McKend contributed to this report.