The Supreme Court took a rare foray into the world of visual arts Wednesday, exploring the delicate intersection between an artist’s freedom to borrow from existing works and the dry confines of copyright law in a case that has the global art world on edge.

All the while, the justices delved into the intricacies of Andy Warhol silkscreens, Norman Lear TV spin-offs and renaissance art.

While most of the arguments were technical, there were brief opportunities to learn more about the justices’ artistic tastes. Justice Clarence Thomas, for instance, revealed he had been a fan of the musician Prince in the 1980s, while Justice Amy Coney Barrett seemed partial to the “Lord of the Rings.”

Probing each side for over an hour, the justices attempted to determine when a new work based on a prior piece is substantially transformative, and when it simply amounts a copycat version of an existing work subject to copyright rules. Several justices worried about how their eventual opinion would impact book-to-movie adaptations, motion pictures and TV sequels.

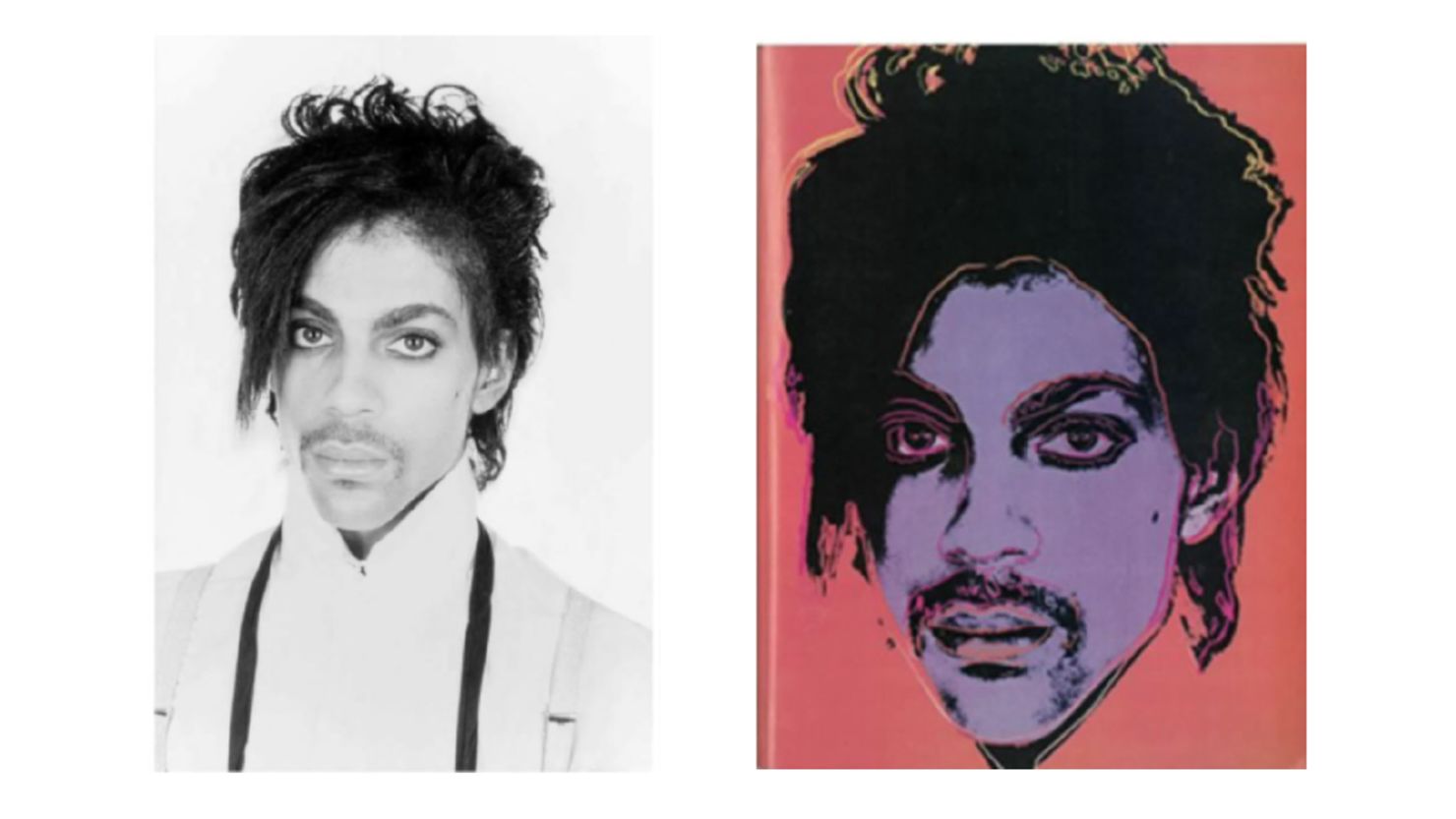

Central to the case is whether the late Andy Warhol infringed on a photographer’s copyright when he created a series of silkscreens of the musician Prince.

At issue is the so called “fair use” doctrine in copyright law that permits the unlicensed use of copyright-protected works in certain circumstances. In the case at hand, a district court ruled in favor of Warhol, basing its decision on the fact that the two works in question had a different meaning and message. But an appeals court reversed – ruling that a new meaning or message is not enough to qualify for fair use.

Now the Supreme Court must produce the proper test that protects artist’s rights to monetize their work, but also encourages new art. They did not seem enthusiastic about a lower court decision, but it was difficult to ascertain how they would finally come out in the case.

Chief Justice John Roberts wondered if the test should revolve around exactly how different the new work is from the existing work. He wondered, for instance, if it would make a difference if Warhol had plastered a giant smile on Prince’s face.

For his part, Justice Samuel Alito questioned whether judges were qualified to focus on the meaning of the work, or if that was a job that should be left to art critics. He noted that it was now impossible to call Warhol, who died in 1987, as a witness to ask him about his intent.

“There can be a lot of dispute about what the meaning or the message is,” Alito said. “I don’t know if you called Andy Warhol as an as a witness what would he say?”

The lawyer responded: “I wish I could answer that question. He’s not with us as you know.”

Thomas was trying to make a point about copyright law, but was derailed by his colleague Justice Elena Kagan. He began his inquiry by saying, “Let’s say I’m a Prince fan, which I was in the 80s”. After a pause, his colleagues seemed taken aback by the revelation.

Finally, Kagan piped in. “No longer?” she asked.

Thomas waited a moment before responding, “Well, so, only on Thursday nights.” When the laughter subsided he launched a multi-part hypothetical question.

The Prince Series and Lynn Goldsmith photographs

“Fair Use protects the First Amendment rights of both speakers and listeners by ensuring that those whose speech involves dialogue with preexisting copyrighted works are not prevented from sharing that speech with the world,” a group of art law professors who support the Andy Warhol Foundation told the justices in court papers.

Lawyers for the Warhol Foundation contend that the artist created the “Prince Series” – a set of portraits that transformed a preexisting photograph of the musician Prince– in order to comment on “celebrity and consumerism.”

They said that in 1984, after Prince became a superstar, Vanity Fair commissioned Warhol to create an image of Prince for an article called “Purple Fame.”

At the time, Vanity Fair licensed a black and white photo that had been taken by Lynn Goldsmith in 1981 when Prince was not well known. Goldsmith’s picture was to be used by Warhol as an artist reference.

Goldsmith – who specializes in celebrity portraits and earns money on licensing – had taken the picture initially while on assignment for Newsweek. Her photos of Mick Jagger, Bruce Springsteen, Bob Dylan and Bob Marley are all a part of the court’s record.

Vanity Fair published the illustration based on her photo – once as a full page and once as a quarter page – accompanied by an attribution to her. She was unaware that Warhol was the artist for whom her work would serve as a reference, but she was paid a $400 licensing fee. The license stated “no other usage rights granted.”

Unbeknownst to Goldsmith, Warhol went on to create 15 additional works based on her photograph. At some point after Warhol’s death in 1987, the Warhol Foundation acquired title to and copyright of the so-called “Prince Series.”

In 2016, after Prince died, Conde Nast, Vanity Fair’s parent company, published a tribute using one of Warhol’s Prince Series works on the cover. Goldsmith was not given any credit or attribution for the image. And she received no payment.

Upon learning about the series, Goldsmith recognized her work and contacted the Warhol Foundation advising it of copyright infringement. She registered her photo with the US Copyright Office.

The Warhol Foundation – believing that Goldsmith would sue – sought a “declaration of noninfringement” from the courts. Goldsmith countersued with a claim of copyright infringement.

A district court ruled in favor of the Warhol Foundation, concluding that the use of the photograph with no permission and no fee constituted fair use.

Warhol’s work was “transformative,” the court said, because it communicated a different message from Goldsmith’s original work. It held that the Prince Series can “reasonably be perceived to have transformed Prince from a vulnerable, uncomfortable person to an iconic, larger-than-life figure.”

The 2nd US Circuit Court of Appeals however, reversed and said that the use of the pictures did not necessarily fall under fair use.

The appeals court said the district court was wrong to assume the “role of art critic” and base its test for fair use on the meaning of the artistic work. Instead, the court should have looked at the degree of visual similarity between the two works.

Under that standard, the court said, the Prince Series was not transformative, but instead “substantially similar” to the Goldsmith photograph and therefore not protected by fair use.

It based its ruling on the fact that a secondary work, even if it adds “new expression” to a source material, can be excluded from fair use. The appeals court said the secondary work’s use of the original source material has to have a “fundamentally different and new” artistic purpose and character “such that the secondary work stands apart from the raw material used to create it.” The court emphasized that the primary work does not have to be barely recognizable within the secondary work, but that at a minimum it must ” comprise something more than the imposition of another artist’s style on the primary work.”

The court said that the “overarching purpose and function” of the Goldsmith photo and the Warhol prints is identical because they are “portraits of the same person.”

“Critically, the Prince Series retains the essential elements of the Goldsmith Photograph without significantly adding to or altering those elements, ” the court concluded.

Limiting freedom of expression?

In appealing the case on behalf of the Warhol Foundation, lawyer Roman Martinez argued that the appeals court had gone badly wrong by forbidding courts from considering the meaning of the work as a part of a fair use analysis.

He warned the court that if it were to embrace the reasoning of the appeals court, it would upend settled copyright principles and chill creativity and expression “at the heart of the First Amendment.”

According to Martinez, copyright law is designed to foster innovation and sometimes builds on the achievements of others.

Martinez stressed that the fair use doctrine – “which dates back at least to the 19th century” – reflects the recognition that a rigid application of the copyright statute would “stifle the very creativity which that laws was designed to foster.”

He noted that Warhol’s works are currently found in collections across the world, including the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Smithsonian collection and the Tate Modern in London. From 2004 through 2014 Warhol auction sales exceeded $3 billion.

Martinez said Warhol made substantial changes by cropping Goldsmith’s image, resizing it, altering the angle of Prince’s face while changing tones, lighting and detail.

“While Goldsmith portrayed Prince as a vulnerable human, Warhol made significant alterations that erased the humanity from the image, as a way of commenting on society’s conception of celebrities as products, not people,” Martinez argued and added, “the Prince series is thus transformative.”

‘Fame is not a ticket to trample other artists’ copyrights’

Lisa Blatt, a lawyer for Goldsmith, told the justices a very different story.

“To all creators, the 1976 Copyright Act enshrines a longstanding promise: Create innovative works, and copyright law guarantees your right to control if, when and how your works are viewed, distributed, reproduced or adapted,” she wrote.

She said that creators and multibillion-dollar licensing industries “rely on that premise.”

She said that the Andy Warhol Foundation should have paid Goldsmith’s copyright fees. Blatt argued that Warhol’s work was almost identical to Goldsmith’s own.

“Fame is not a ticket to trample other artists’ copyrights,” she said.

The Biden administration is supporting Goldsmith in the case.

Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar noted, for example, that book-to-film adaptations often introduce new meanings or messages, “but that has never been viewed as an independently sufficient justification for unauthorized copying.” She said that Goldsmith’s ability to license her photograph and earn fees has been “undermined” by the Warhol Foundation.

The Art Institute of Chicago and other museums told the court that the appeals court decision has caused uncertainty not only for the work of arts themselves but the market for copies of works the museum creates through catalogues, documentaries and websites.

Lawyers for the museums also noted that the lower court opinion “failed to consider” longstanding artistic traditions of using elements of pre-existing works in new works and asked the Supreme Court to revisit the appeals court ruling.

In the Baroque era, for example, Giovanni Panini painted modern Rome (pictured in court papers) depicting a gallery showing famous art. Included are copies of preexisting works including Michelangelo’s Moses, Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s statutes of Constantine, David, Apollo and Daphne and his fountains of Piazza Navona. Contemporary artists also continue to leverage preexisting artwork, the museums argued. The street artist Banksy, for example, painted a piece, “Girl with a Pierced Eardrum” onto a building in Bristol. It was in reference to Johannes Vermeer’s masterpiece, “Girl with a Pearl Earring” from 1665.

“All of these works would not be considered transformative under the Second’s circuit’s” approach, the museums argued.

This story has been updated with additional details.