The Ukrainians’ bodies lay side-by-side on the grass, the earth beside them splayed open by a crater. Dragged to the spot by Russian mercenaries, the victims’ arms pointed to where they had died.

“Let’s plant a grenade on them,” a voice says in husky Russian, in what appears to be a plan to booby-trap the bodies.

“There is no need for a grenade, we will just bash them in,” another says of the Ukrainian soldiers who will come to collect the bodies. The mercenaries then realize they have run out of ammunition.

These events seen and heard on battlefield video, exclusive to CNN, along with access to Wagner recruits fighting in Ukraine, and candid, rare interviews CNN has conducted with a former Wagner commander now seeking asylum in Europe, combine to give an unprecedented look at the state of Russia’s premier mercenary force.

While problems of supply and morale, as well as allegations of war crimes have been well documented among regular Russian troops, the existence of similar crises among Wagner mercenaries, often described as President Vladimir Putin’s off-the-books shock troops, is a dire omen for Russia’s war in Ukraine.

In the shadow of the Kremlin

Wagner forces have for several years enjoyed global notoriety. But as Putin’s “special military operation” in Ukraine comes apart at the seams, and the announcement of a “partial mobilization” for much-needed conscripts has prompted more than 200,000 Russian citizens to flee to neighboring countries, the cracks in this supposedly elite force are showing.

Since its creation in 2014, Wagner’s mandate, international footprint and reputation have swelled. Widely considered by analysts to be a Kremlin-approved private military company, its fighters have battled in Ukraine since the Russian invasion in 2014 and in Syria, as well as operating in several African countries, including Sudan, Libya, Mozambique, Mali and the Central African Republic.

With a reputation in Russia as a reliable and valuable force, Wagner private soldiers have bolstered Moscow’s global interests and military resources, already stretched fighting a war in Syria in support of the Assad regime. As CNN has reported, their deployments have often been key to Russian control of lucrative resources, from Sudanese gold to Syrian oil.

Read CNN’s special report on Putin’s Private Army.

Flaunting modern equipment in recruiting videos, with heavy weapons and even helicopters, they resemble US Special Forces.

“I am convinced that if Russia did not use mercenary groups on such a massive scale, there would be no question of the success that the Russian army has achieved so far,” Marat Gabidullin – a former Wagner commander who was once in charge of 95 mercenaries in Syria – told CNN.

In touch with former comrades now fighting in Ukraine, Gabidullin said that Russia’s use of mercenaries has ramped up as the Kremlin’s execution of its war has fallen into disarray. Ukraine’s Defense Minister Oleksiy Reznikov told CNN that Wagner troops were being deployed in the “most difficult and important missions” in Ukraine, playing a key role in Russian victories in Mariupol and Kherson.

The Kremlin did not respond to CNN’s requests for comment.

Limited official information about Wagner and long-standing Kremlin denials about its existence and ties to the Russian state have only added to its infamy and allure, while helping the group to cloud analysis of its exact capabilities and activities.

In reality, though, Wagner – like Russia – is struggling in Ukraine, according to the video testimony of the group’s own mercenary fighters.

Lack of experience

More than seven months of fighting have thrown a harsh light on failings in Russia’s military performance in Ukraine. Russia’s small gains, especially compared to Putin’s initial ambitious targets in the war, have come at huge cost, decimating frontline units and starving many of manpower, as well as critically important experience.

Battlefield experience is one of two factors ex-Wagner commander Gabidullin – who left the group in 2019 and has since published a memoir of his time working for them – says separates mercenaries from regular Russian troops, the other being money.

“The backbone of these groups was always made up of very experienced people who had passed through several wars anyway,” he told CNN.

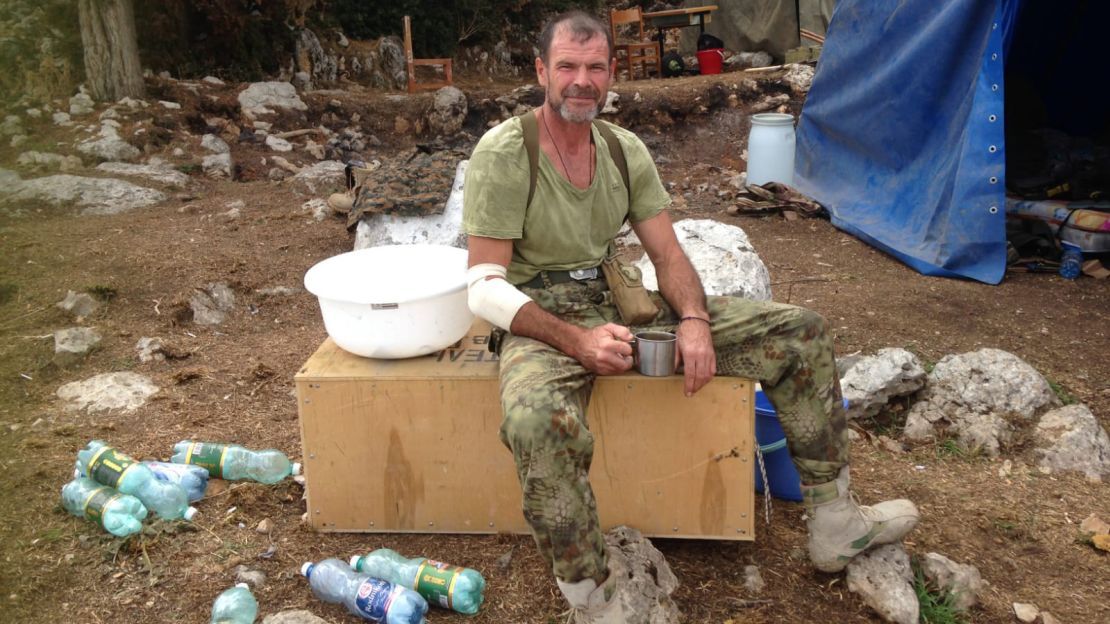

After serving as a junior officer with an airborne unit in the dying days of the Soviet Union, Gabidullin returned to military life as a Wagner recruit following Russia’s 2014 invasion of eastern Ukraine. He said many key Wagner personnel may, like him, have previously fought in Ukraine as well as in Syria, gaining valuable combat experience alien to most regular Russian troops.

“They have more weighty, more meaningful experience than the army. The army are young soldiers who were forced to sign a contract, they have no experience,” he said.

It’s what makes such paramilitary forces in Ukraine, of which Wagner is just one, so valuable to Russia.

“The Russian army cannot handle [the war] without mercenaries,” according to Gabidullin, adding that there’s “a very big myth, a very big obfuscation about a strong Russian army.”

Today, at least 5,000 mercenaries tied to the Wagner group are operating with Russian forces in Ukraine, Andrii Yusov, a spokesperson for Ukraine’s defense intelligence agency who has been monitoring Wagner in Ukraine, told CNN. This figure was backed up by a French intelligence source who noted that some Wagner fighters had left the African continent to bolster the group’s efforts in Ukraine.

The Kremlin has increasingly relied on Wagner fighters as assault troops, according to Ukraine’s defense ministry. Hidden from official Russian death counts and available for deniable operations, they’ve borne a burden of casualties that have been politically sensitive for Putin in Russia.

“Wagner has been suffering high losses in Ukraine, especially and unsurprisingly among young and inexperienced fighters,” according to a senior US defense source speaking in September.

A simple equation underlies the employment of Wagner forces, according to Gabidullin: “Russian peace for American dollars.”

The mercenaries can earn up to $5,000 per month.

Wagner fighters have even been offered bonuses – all paid in US dollars – for wiping out Ukrainian tanks or units, according to a senior Ukrainian defense source and based on the intelligence gathered on Wagner since the start of the war by Ukrainian authorities.

According to the UK’s Ministry of Defense, Wagner fighters have also been allocated specific sectors of the front line, operating almost as normal army units, a stark change from their history of distinct, limited missions in Ukraine.

Yusov also said that Wagner is increasingly being used to patch holes in the Russian front line. This was also confirmed by a US senior defense official, who added that Wagner is being used across different front lines unlike Chechen fighters, for instance, who are focused around the Russian offensive aimed at Bakhmut.

That has led to significant logistical challenges, he says, with the need to supply Wagner troops with ammunition, food and support for extended operations, all while Ukraine has upped its attacks on Russia’s logistics.

Bodycam footage purportedly from Wagner fighters in August passed to CNN by the Ukrainian defense ministry shows mercenaries complaining of a lack of body armor and helmets. In another video a fighter complains about orders to attack Ukrainian positions when his unit is out of ammunition.

Shoes to fill

Wagner’s ranks have also been depleted by battlefield losses. In response, they’ve turned to unusually public recruitment.

Billboards have sprung up in Russia calling for new recruits to Wagner. Adorned with a phone number and picture of camouflage-clad fighters, their slogan – “Orchestra ‘W’ Awaits You” – alludes to Wagner’s past nickname as the “orchestra.”

The wide net cast by the group’s recruiting efforts matches a shift from its past secrecy. Even Putin ally Yevgeny Prigozhin finally admitted his role as Wagner chief in late September, having spent years trying to distance himself from the mercenary group through repeated denials, and even taking Russian media outlets investigating him to court.

Wagner’s invitations to contact recruiters have also spread via social media and online. One recruiter contacted by CNN offered a monthly salary of “at least 240,000 rubles” (about $4,000) with the length of a “business trip” – code for a deployment – of at least four months. Much of the recruiter’s message listed medical conditions that excluded applicants from joining: from cancer to hepatitis C and substance abuse.

In contrast to its image as a military elite organization, a Wagner recruiter had one startling admission regarding recruits when contacted by a CNN journalist: no military experience necessary.

The message finished with a code word – “Morgan” – that applicants were to give at the gate of the Wagner facility in Krasnodar, Russia.

Jailhouse recruits

In September, video surfaced appearing to be Prigozhin recruiting prisoners from Russian jails for Wagner His offer: a promise of clemency for six months’ combat service in Ukraine, propping up Russia’s flailing invasion.

It’s a move that would have been unthinkable months ago for the private military company once considered one of the most professional units in the Kremlin’s arsenal.

“An act of desperation” is how the ex-Wagner commander Gabidullin described the appeal.

Prigozhin’s apparent jailhouse recruitment drive matches broader Russian efforts to mobilize the country’s prison population for combat, offering monthly salaries worth thousands of dollars and death payments of tens of thousands of dollars to recruits’ families.

For both Wagner comrades and their Ukrainian adversaries, that’s worrying.

“[Wagner] are ready to send anyone, just anyone,” Ukrainian Prosecutor Yuriy Belousov, told CNN. “There is no criteria for professionalism anymore.”

Working on Ukrainian investigations into possible Russian war crimes, Belousov fears that this lax recruiting will see the scale of war crimes increase.

Although direct recruitment from prisons is a new step, Gabidullin said that a criminal record hadn’t been an obstacle to employment with Wagner. He himself says he had served three years in prison for murder and told CNN of prominent Wagner commanders who had served around the world with the group after prison sentences.

The enemy within

Wagner’s struggles in Ukraine have set in motion a wider problem: discontent in its ranks. For a group that depends on the appeal of its salaries and work, that’s critical.

From intercepted phone calls, Ukrainian intelligence services in August noted a “general decline in morale and the psychological state” of Wagner troops, Ukrainian defense intelligence spokesman Yusov said. It’s a trend he’s also seen in Russian troops more broadly.

The reduction in Wagner recruitment requirements point to demoralization too, he said, and the number of “truly professional soldiers who are willing to volunteer to fight with Wagner” is also decreasing.

Ex-commander Gabidullin, who says he talks to his old comrades on an almost daily basis, explained that this demoralization was due to their dissatisfaction “with the overall organization of the fighting: [the Russian leadership’s] inability to make competent decisions, to organize battles.”

For one mercenary who contacted Gabidullin for advice, that incompetence was too much. “He called me and said: ‘That’s it, I won’t be there anymore. I’m not taking part in this anymore,’” Gabidullin told CNN.

And as Russia’s prospects of victory in Ukraine – or even claiming a positive outcome – look thin, life as a Russian mercenary doesn’t hold the same appeal it might once have had.

“It may be that the money isn’t worth it anymore,” Ukrainian prosecutor Belousov said.

In one of the many videos streaming out of Ukraine’s frontlines, the grim reality of Wagner’s war is plain to see in footage provided to CNN, which allegedly shows the group’s operations.

In one clip, a fallen Wagner mercenary lies, in death, almost peacefully, his left hand gently gripping the black earth. Around him, the battlefield smolders alongside dead bodies and the flaming wreckage of their armored vehicles. Occasional shots crackle through the smoke.

“I’m sorry, bro, I’m sorry,” the soldier’s comrade says, lightly patting his back, stripped of his shirt by the battle that killed him. “Let’s get out of here, if they shoot us, we’ll lie next to him.”

Amandine Hess, Darya Markina, Victoria Butenko and Josh Pennington contributed to this report.