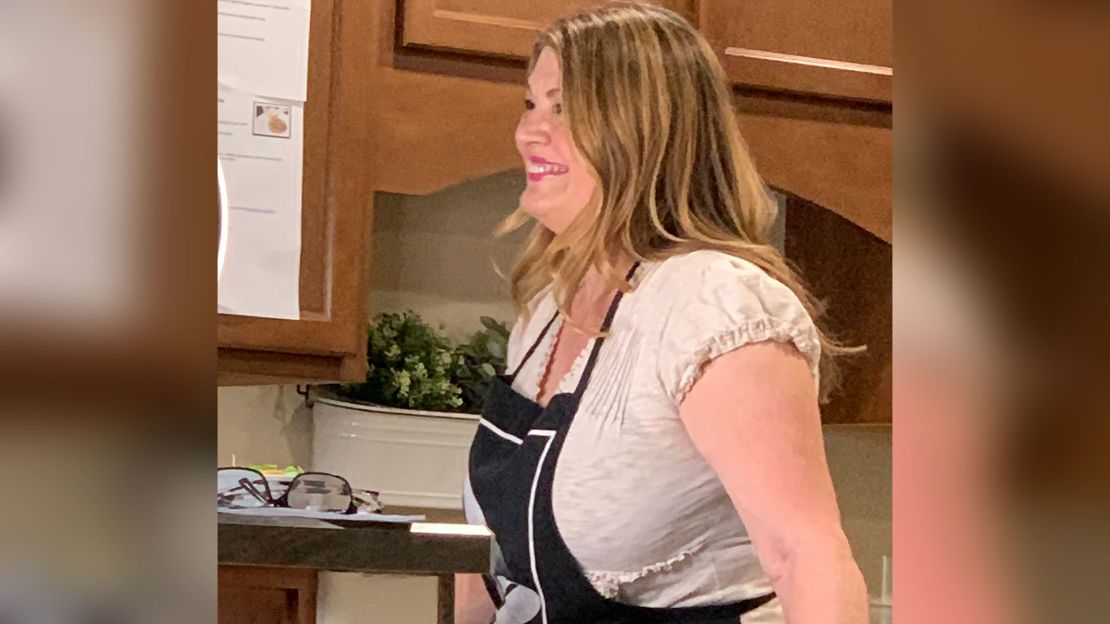

Lisa Altman used to take pride in being able to eat what she wanted without worrying much about the cost.

When she was growing up, seconds weren’t served and side dishes were rare. “My mom had a budget every week, and she stuck to it,” she said. “As I got older and became more financially independent, having a full pantry and being able to eat what I wanted was a sign of success for me,” she added.

“It was very humbling to have to go from that situation to where we’re at right now.”

Altman and her wife live in Austin, Texas with their three children. Recently, they’ve been relying mostly on one income. Their reduced earnings, coupled with inflation, have dealt a blow to their finances.

And that has changed, radically, the way they eat. Altman is not alone in making big changes.

We asked CNN readers how inflation has impacted their eating habits, and many mentioned dining out less often, buying less meat and giving up splurges. Some said they are very worried about the future.

Food prices have spiked 11.4% over the past year, the largest annual increase since May 1979, according to data released in mid-September by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Grocery prices jumped 13.5% and restaurant menu prices increased 8% in that period.

Consumers are responding by looking for deals and switching to generic brands, according to July data from the market research firm IRI. Companies like Tyson (TSN) have noticed customers are switching from beef to chicken, and Applebee’s and IHOP have reported an uptick in higher-income customers who are likely trading down from pricier restaurants. Some people may be dining out less often, or avoiding restaurants altogether.

For those who struggled to buy food even before prices shot up, rising costs could mean falling into food insecurity, a state of unreliable access to affordable food.

“If food prices continue to increase at a rate that outpaces increases in wages, that is the inevitable consequence,” said Jayson Lusk, head of the agricultural economics department at Purdue University. “The last time we had a big run up in food insecurity rates was in the wake of the Great Recession.” Last year, about 10.2% of US households were food insecure, according to the USDA, slightly below the 10.5% rate in 2020 and 2019.

Even for those not at risk of hunger, the surges in food prices are jarring.

Food “matters a lot to our self esteem, our mood,” said William Masters, a professor at Tufts University’ school of nutrition science and policy who is also a member of the economics department faculty. “Not being able to buy the foods that people are used to — that your children are asking for, that your family wants — that’s a really hard thing,” he said. “Any disruption of habit is very, very hard.”

Giving up on simple pleasures

For Carol Ehrman, cooking is a joyful experience.

“I love to cook, it’s my favorite thing to do,” she said. She especially likes to cook Indian and Thai food, but stocking the spices and ingredients she needs for those dishes is no longer feasible. “When every ingredient has gone up, that adds up on the total bill,” she said.

“What used to cost us $250 to $300 … is now $400.” Ehrman, 60, and her husband, 65, rely on his social security income, and the increase was stretching their budget. “We just couldn’t do that.”

About six months ago, she realized she had to change the way she shops for groceries.

In an effort to bring their immediate costs down, Ehrman stopped shopping in bulk as often as she used to. Now, she hunts for sales, avoids buying beef, and opts for boxed wine instead of nice bottles when she buys wine at all. She’s also cooking simpler meals, and saying goodbye to dinner parties.

Ehrman haș even given up preparing basic items, like tomato sauce, because of the expense, opting instead for a pre-packaged version.

“I know that I can make it much healthier,” she said. And “it always tastes so much better.” Those fresh ingredients are just too pricey now.

Ehrman’s husband is retired due to chronic health problems, and it’s been difficult for her to work because of her own health issues — she recently had pacemaker and heart catheterization procedures. The couple, who live in Billings, Montana, were frugal before the current spike in prices, enjoying simple pleasures. But now, even those are out of reach.

“Before, we at least found joy in being home and having friends over and family over, cooking and sitting around the table and just being content,” she said. Now, “I’m not entertaining at all. It’s really sad.”

From Coke to Pepsi

Rick Wichmann, 64, and his wife have been dining out less often in recent years, due to the pandemic and in an effort to eat healthier. With menu prices rising because of inflation, they see no reason to change their habits.

“Eating out is expensive,” he said, noting that he’s often happier with home-cooked meals than restaurant food anyway.

But grocery shopping is also more expensive. Over the past year, Wichmann noticed that he had been spending about 25% more shopping for groceries for himself, his wife and their son than he used to.

To help mitigate those costs, Wichmann, who lives in Brookline, Massachusetts, started going to different grocers. He avoids Whole Foods and Stop & Shop, opting instead for Costco and the local chain Market Basket.

He’s also switched to store brands, if he feels the quality is the same, and will sometimes choose products based on price rather than brand loyalty — like, for example, buying Pepsi when it’s cheaper, when he’d otherwise choose Coke.

Wichmann also pays attention to events like weather, and how they might affect prices. When he saw reports of a possible tomato shortage due to droughts in California, he took notice. The next time he saw tomato sauce on sale he stocked up on enough to last for months.

A vegetable garden in the front lawn

Like Wichmann, Jenni Wells, 38, pays attention to weather patterns and food systems. A former chef and rancher, she noticed price increases well before the current bout of inflation.

“My alarm bells started going off for prices going up in 2019,” she said, when devastating floods in the midwest drowned livestock and destroyed grain stocks. Wells decided back then that she’d like to be more self sufficient.

“I saw the food prices going up, and I realized that it was going to quickly overwhelm our budget,” she said. So in February, she ripped up the grass in the front lawn of her home in Fort Worth, Texas, which she shares with her husband and best friend, and planted a vegetable garden.

“I just wanted to see what I could grow for myself,” she said. This year, she’s managed to grow broccoli, cauliflower, okra, tomatoes, peppers, squashes and more in her garden.

There are upfront and maintenance costs for the garden, of course. And it’s not easy to grow vegetables. But the household’s weekly grocery spending, excluding meat, has fallen from about $200 to $50, she said.

With the money left over, Wells and her household have been able to eat at restaurants, something that would have been “too much of a luxury” had they still been spending $200 a week on groceries. And there’s the satisfaction of growing your own food.

“There’s a huge sense of reward,” she said. “I feel pride in every meal that I make with it.”

Changing for good

Some consumers have made changes because of current circumstances that they plan to hold onto.

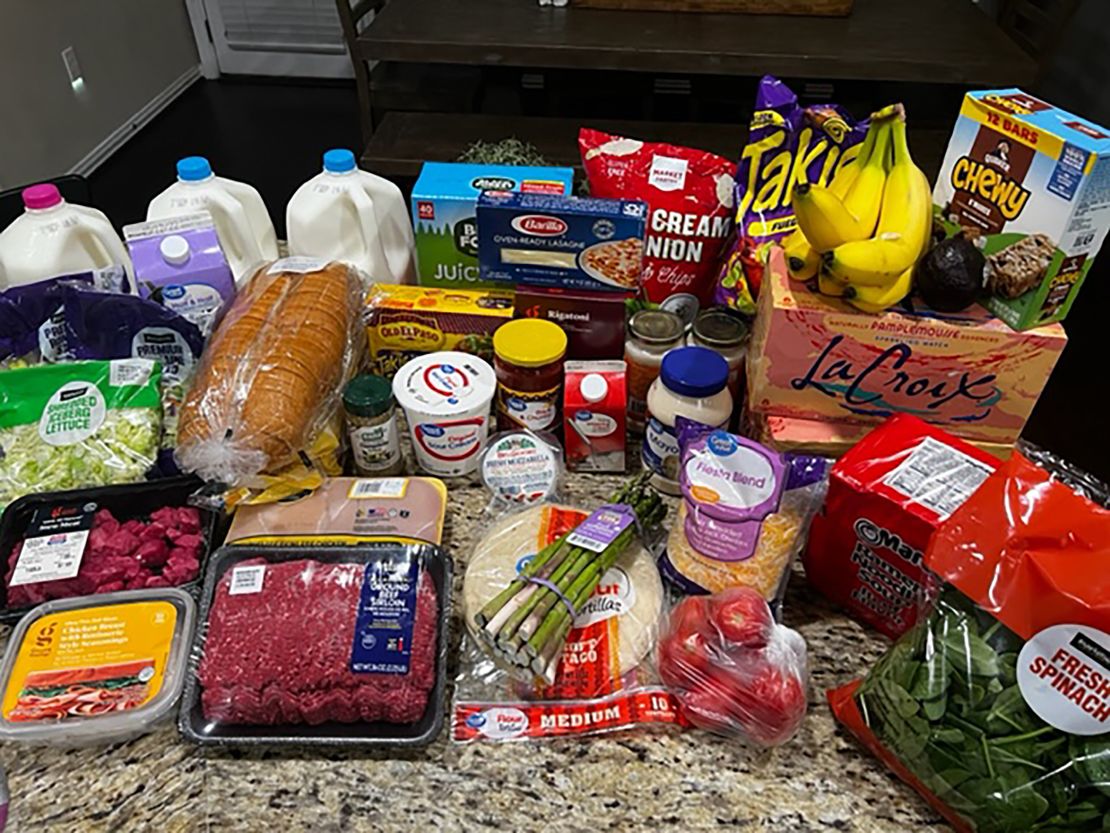

Now, Altman, the Austin parent of three, aims to keep her grocery bill to about $100 to $125 per week by buying store brands, lots of pasta and a limited amount of protein each week.

Instead of ordering in or grilling steaks or ribs, Altman’s family eats more basic meals with smaller portions. “Now our meals consist of one primary dish, and that’s it, maybe some bread on the side, or a salad.” If they go out to eat, they’ll pick up a fast food meal with a few sides, like one burger and two fries, split the items and have beverages at home.

When Altman is able to afford it, she’ll go back to buying more fruits and veggies. But she’s hoping some habits, like encouraging her children to avoid mindless eating and reducing food waste, will stick.

“I’m not going to be spending $1,200 a month on groceries,” she said. “This has taught us that that’s not necessary.”