Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

Construction workers breaking ground in 2004 on a shopping mall in Norwich, England, found 17 bodies at the bottom of a 800-year-old well.

The identity of the remains of the six adults and 11 children and why they ended up in the medieval well had long vexed archaeologists. Unlike other mass burials where skeletons are uniformly arranged, the bodies were oddly positioned and mixed – likely caused by being thrown head first shortly after their deaths.

To understand more about how these people died, scientists were recently able to extract detailed genetic material preserved in the bones thanks to recent advances in ancient DNA sequencing. The genomes of six of the individuals showed that four of them were related – including three sisters, the youngest of whom was five to 10 years old. Further analysis of the genetic material suggested that all six were “almost certainly” Ashkenazi Jews.

The researchers believe they all died during antisemitic violence that wracked the city – most likely a February 1190 riot related to the Third Crusade, one of a series of religious wars supported by the church – as described by a medieval chronicler. The number of people killed in the massacre is unclear.

“I’m delighted and relieved that twelve years after we first started analysing the remains of these individuals, technology has caught up and helped us to understand this historical cold case of who these people were and why we think they were murdered,” said Selina Brace, a principal researcher at the Natural History Museum in London and lead author on the paper, said in a news release.

Judaism is primarily a shared religious and cultural identity, the study noted, but as a result of a long-standing practice of marrying within the community, Ashkenazi Jewish groups often carry a distinctive genetic ancestry that includes markers for some rare genetic disorders. These include Tay-Sachs disease, which is usually in fatal in childhood.

The researchers found that the individuals in the well shared a similar genetic ancestry to present-day Ashkenazi Jews, who, according to the study, are descendants of medieval Jewish populations with histories mainly in northern and Eastern Europe.

“Nobody had analyzed Jewish ancient DNA before because of prohibitions on the disturbance of Jewish graves. However, we did not know they were likely Jewish until after doing the genetic analyses,” evolutionary geneticist and study coauthor Mark Thomas, a professor at University College London, said in the release.

“It was quite surprising that the initially unidentified remains filled the historical gap about when certain Jewish communities first formed, and the origins of some genetic disorders,” he said.

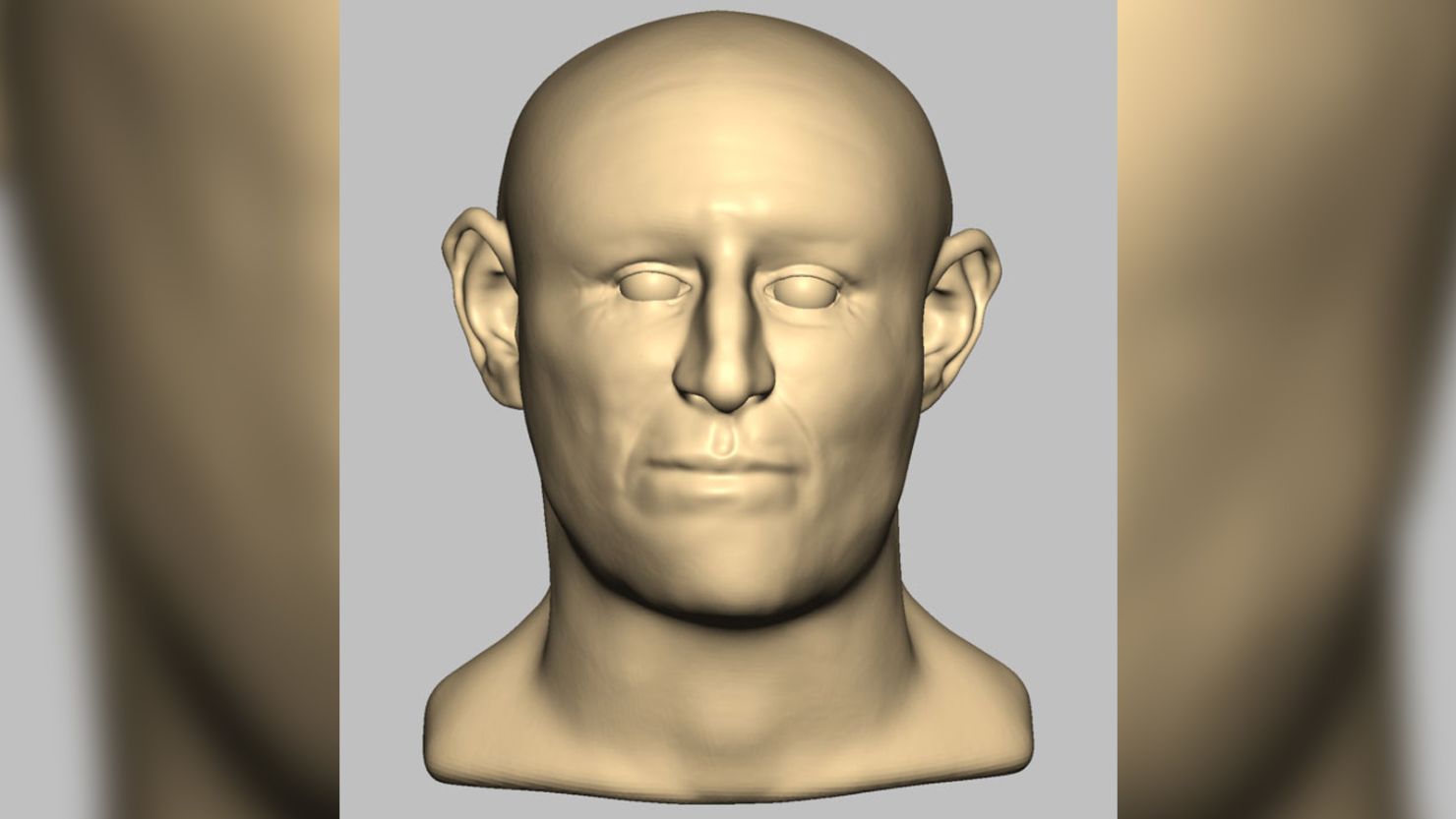

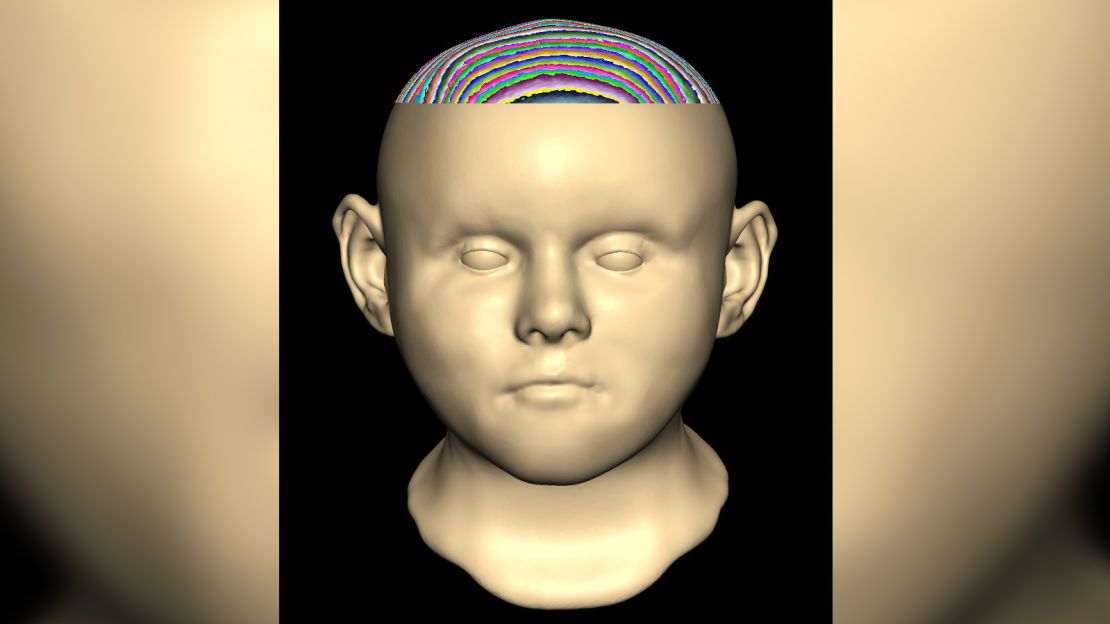

The DNA analysis also allowed the researchers to infer the physical traits of a toddler boy found in the well. He likely had blue eyes and red hair, the latter a feature associated with historical stereotypes of European Jews, the study, published Tuesday by the journal Current Biology, said.

In the medieval manuscript “Imagines Historiarum II,” chronicler Ralph de Diceto paints a vivid picture of the massacre:

“Many of those who were hastening to Jerusalem determined first to rise against the Jews before they invaded the Saracens. Accordingly on 6th February [in 1190 AD] all the Jews who were found in their own houses at Norwich were butchered; some had taken refuge in the castle,” he wrote, according to the news release.

The well was located in what used to be the medieval Jewish quarter of Norwich, with the study noting that the city’s Jewish community were descendants of Ashkenazi Jews from Rouen, Normandy, who were invited to England by William the Conqueror, who invaded England in 1066.

The link with the 1190 riot isn’t definitive, however.

Radio carbon dating of the remains suggested the bodies ended up in the well at some point between 1161 to 1216 – a period which includes some well-documented outbreaks of antisemitic violence in England but also covers the Great Revolt of 1174 during which many people in the city were killed.

“Our study shows how effective archaeology, and particularly new scientific techniques such as ancient DNA, can be in providing new perspectives on historical events,” Tom Booth, a senior research scientist at the Francis Crick Institute, said in the news release.

“Ralph de Diceto’s account of the 1190 AD attacks is evocative, but a deep well containing the bodies of Jewish men, women, and especially children forces us to confront the real horror of what happened.”