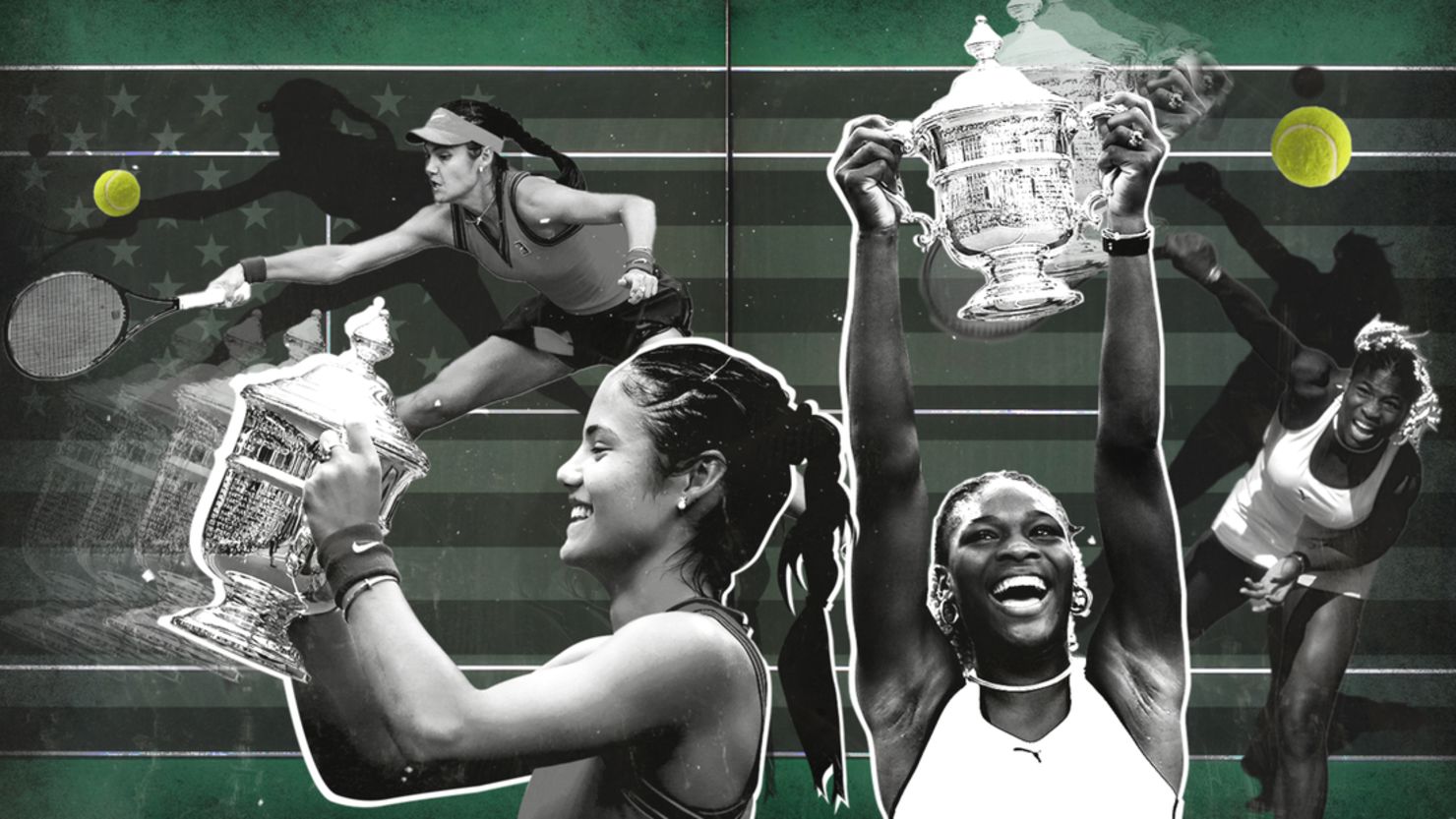

When Emma Raducanu won the US Open last year, she dropped her racket, sank to the floor and covered her face in her hands.

It was a familiar scene, one repeated throughout the years by first-time grand slam winners; Daniil Medvedev also fell to the floor as he won his maiden grand slam a day after Raducanu, as did Dominic Thiem a year before that.

Even 23-time grand slam winner Serena Williams, who will “evolve away from tennis” after this tournament, seemed shocked when she won her first at the 1999 US Open.

But after this euphoric moment, there often seems to be a gap before that pinnacle can be reached again – 34 of the 45 first-time grand slam winners since 2000 have endured a wait of at least a year for another, if they won a second title at all.

Williams herself had to wait two-and-a-half years to win her second grand slam.

‘Depth of self-belief unlike anything else’

Alongside Williams, tennis has been dominated for 20 years by players for whom losing seems more difficult than winning – Roger Federer, Rafael Nadal and Novak Djokovic.

Winning considerably more than one grand slam has become normalized, even expected, somewhat obscuring the difficulties of claiming that first one.

In tennis, a lonely individual sport requiring constant travel for 10 months of the year across different time zones and environments, the psychological pressure of winning a grand slam is different compared to other sports.

“A lot of times when there’s social support, I look to my left, I look to my right, I see my teammate to give me a fist pump … That type of social support can go a really long way for an individual to manage performance anxiety,” sports psychologist Dr Jarrod Spencer explains to CNN Sport.

“But [when] it’s just one-on-one, you look to your left and your right and you realize that you’re alone. That requires a depth of self-belief that is unlike anything else.”

And with a unique scoring system that creates jeopardy on almost every point, much of playing tennis is “actually up in the head,” as Eurosport expert and former world No. 7 Barbara Schett tells CNN.

Winning would seem to create a virtuous circle, deepening self-belief which in turn builds confidence to be deployed at crucial points in tight matches.

“When I was top 10,” Schett says, “I was at the stage where I went on the court and I thought, ‘I’m not going to lose this match. There’s absolutely no chance.’ I can only imagine how … the legends of our game would feel when they’re stepping on the court.”

Schett played Williams three times in her career and never defeated her. They met for the last time at the French Open in 2003 and Schett lost 6-0 6-0.

“I had already lost the match before I played against her because her presence on the court was just unbelievable,” Schett recalls.

“I just felt like, ‘How am I going to beat this girl? She’s physically so much better. She plays so much harder. She believes in herself. And I had better just go to the locker room.’”

But winning can lead to a sense of fallibility as well as invincibility, creating a new set of expectations and goals to be reckoned with.

‘Perfection doesn’t exist’

In the aftermath of Raducanu’s US Open triumph, pundits rushed to hail her as a future multiple grand slam winner on account of her powerful groundstrokes and consistently aggressive return of serve.

She gathered sponsor after sponsor and PR experts branded her with the potential to become Britain’s first billion-dollar sport star.

“Everyone just expected me to win every single tournament I was ever going to play again. It’s a bit unrealistic because perfection just doesn’t exist,” Raducanu said in a recent interview with Nike.

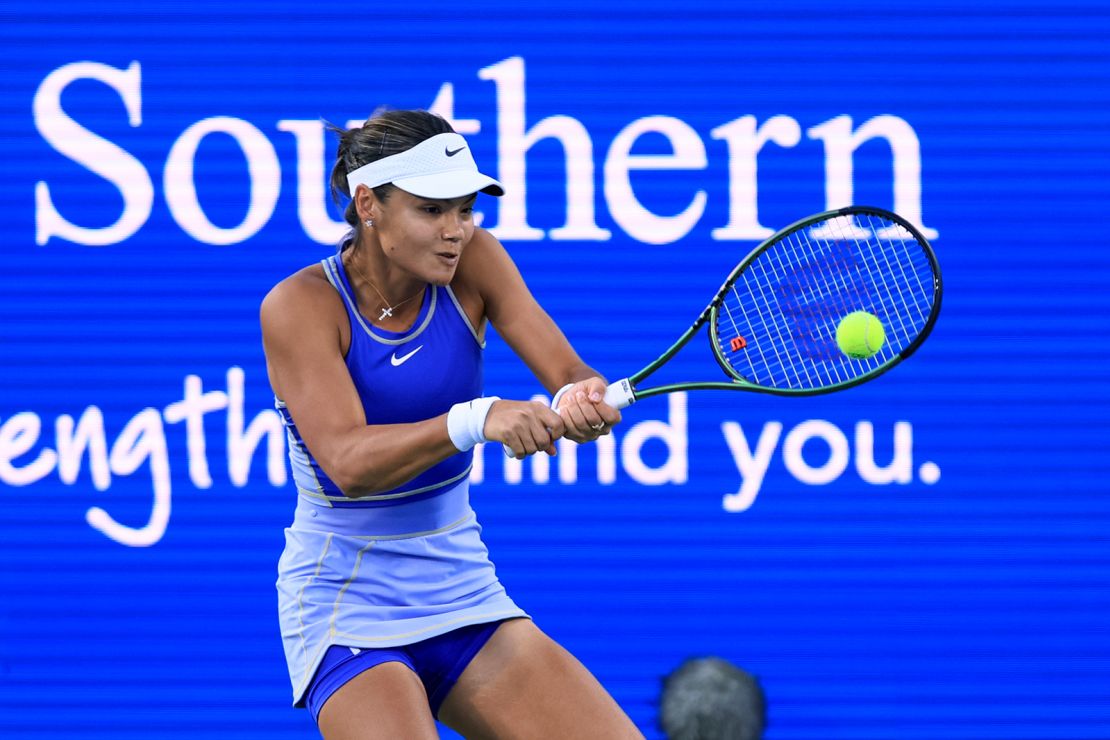

A succession of injuries has marred Raducanu’s first full year on tour with blisters, back issues, side strains and hip injuries all forcing her to withdraw from various tournaments throughout the season.

In her three grand slam appearances since those magical two weeks in New York, Raducanu has reached just the second round, falling to players ranked lower than her on every occasion.

“There’s a lot of expectation externally on her,” Schett says. “Obviously, she wants to win another one. She wants to prove to everybody that she wasn’t a one day wonder or a two week wonder and that she can do more, but the pressure and the expectations are extremely high in her case.”

For a 19-year-old competing in her first year on the WTA Tour, it has been a solid, if unremarkable season, but the stratospheric expectations surrounding the Brit have reframed every loss as something resembling a catastrophic failure.

‘That point of satiation’

Goals, as well as expectations, alter in the aftermath of a major victory like a grand slam title.

Dominic Thiem has experienced a similar trajectory to Raducanu since winning his maiden grand slam at the 2020 US Open, plummeting out of the upper echelons of the game to a ranking as low as world No. 352.

A lingering wrist injury hampered the Austrian, as did coming to terms with his new status as a grand slam winner.

“When you fight for a goal, you leave everything for it and you achieve it, everything changes,” Thiem told the Austrian newspaper Der Standard in April 2021.

“However, in tennis, everything goes very fast, you don’t have time to enjoy the victory, and if you are not 100%, you lose. It happened to me this year.”

To explain the psychological effects of achieving a major goal, Spencer compares it to a more everyday experience – eating.

“When you’re hungry, you’ll do whatever it takes to get some food,” he says. “And then once you reach that point of satiation where you just feel full, then it’s like, I can’t eat another bite, I don’t want anything for quite some time.”

“And so it’s very normal and natural, just like eating a big meal that sometimes an athlete, after they win something really significant might just lose a little bit of drive for a little while.”

The emotional costs of elite sport are becoming more evident every year as athletes begin to talk openly about mental health and its importance.

At the French Open last year, four-time grand slam winner Naomi Osaka withdrew to protect her mental health after a furor erupted following her refusal to conduct post-match press conferences.

Afterwards, she revealed that she had “suffered long bouts of depression” and “huge waves of anxiety” since her first grand slam triumph in 2018.

Iga Swiatek, meanwhile, hailed her sports psychologist Daria Abramowicz for the role that she played helping her win the French Open in 2020.

‘Many, many things have happened’

Managing the “emotional energy” which sport depletes is key to recalibrating an athlete’s goals and expectations, Spencer explains.

Thiem has begun to rebuild after his year in the wilderness, winning his first ATP Tour match in 14 months with a victory in the first round against of the Bastad Open against Finland’s Emil Ruusuvuori in July 2022.

“My last victory was in Rome in 2021, it feels like a different world somehow,” he said afterwards, according to the BBC.

“Many, many things happened. It was tough, but it was also a very good experience, I think, for life in general. I’m so happy that I got this first victory here today.”

In recent weeks, Raducanu too has shown flickers of the form that propelled her to tennis stardom with victories against Williams and Victoria Azarenka at the Western & Southern Open in Cincinnati before she lost to Jessica Pegula in the third round – just her second ever match against a top 10 player.

She will face Alizé Cornet in the first round of the US Open as she begins her title defense, while Thiem – also appearing at the tournament for the first time since winning it – will play Pablo Carreño Busta.