A version of this story appears in CNN’s What Matters newsletter. To get it in your inbox, sign up for free here

The central question surrounding the FBI’s search of Mar-a-Lago last weekis the one that remains most unanswered: What documents did former President Donald Trump have and why is the government so intent on getting them back?

There are other questions, of course.Did he take the material because he thought they were “cool,” like some kind of trophy? Or did he see some advantage in having them, The New York Times reporter Maggie Haberman wondered during an appearance on CNN’s “New Day” on Monday.

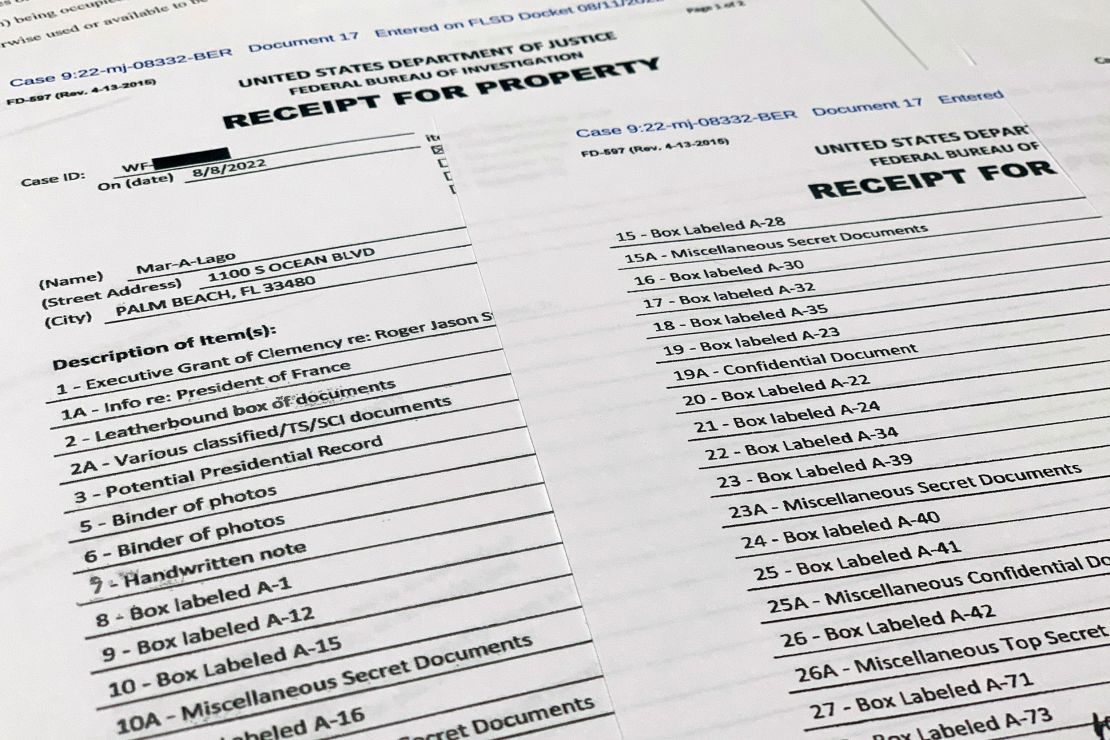

Were the documents related to Roger Stone’s pardon by Trump somehow key evidence? What is behind the appearance of material onthe “President of France”in the receipt for what was taken?

The imagination runs wild in the absence of facts.

Trump has now demanded the documents be returned, even though presidential papers, under US law, are not his property.

The most tantalizing detail is that 11 sets of documents were classified.

It’s shining a light on the system of classification by which the government hides information from its people in the name of everyone’s national security.

More than a million people have Top Secret clearance

It’s actually a very large universe of people with access to Top Secret data.

The Director of National Intelligence publishes what is described as an annual report, “Security Clearance Determinations,” although the most recent one I could find was from 2017.

In it, more than 2.8 million people are described as having security clearance as of October 2017 – more than 1.6 million have access to either Confidential or Secret information and nearly 1.2 million are described as having access to Top Secret information.

There are additional people who have security clearance but don’t currently have access to information. This includes civilian employees, contractors and members of the military.

Agencies control their own classified data. They are supposed to declassify it

That doesn’t mean more than 1 million people have access to whatever Top Secret documents were lying around Mar-a-Lago. Each agency that deals in classification has its own system and is supposed to be involved in declassifying its own documents.

Trump’s defenders have argued he had put in place an order to declassify any documents he took from the Oval Office to the residence during his time in the White House, although professionals have said this claim can’t be true.

“The idea that the president can declassify documents simply by moving them from one physical location to another is nonsense on so many levels,” said Shawn Turner, a CNN analyst and former director of communication for US National Intelligence, during a Monday appearance on “Inside Politics.”

There’s an official process

Turner said the process for declassification must include signoff from the agency that classified the information in the first place in order to protect the intelligence-gathering process, its sources and methods.

Presidents have periodically used executive orders to update the official system by which classified information is declassified.

Most recently, then-President Barack Obama put in place Executive Order 13526 in 2009. That’s still the official policy since neither Trump nor President Joe Biden updated it.

The government might soon change the process

Biden started a review of how classified data is handled earlier this summer. Here’s an exhaustive Congressional Research Service report on the declassification process.

Biden’s review will reexamine the three general levels of classification.

Levels of classification

CNN’s Katie Lobosco wrote a very good primer on classified data last week. Here’s her description of the three levels of classification:

Top Secret – This is the highest level of classification. Information is classified as Top Secret if it “reasonably could be expected to cause exceptionally grave damage to the national security,” according to a 2009 executive order that describes the classification system.

A subset of Top Secret documents known as SCI, or sensitive compartmented information, is reserved for certain information derived from intelligence sources. Access to an SCI document can be even further restricted to a smaller group of people with specific security clearances.

Some of the materials recovered from Trump’s Florida home were marked as Top Secret SCI.

Secret – Information is classified as Secret if the information is deemed to be able to cause “serious damage” to national security if revealed.

Confidential – Confidential is the least sensitive level of classification, applied to information that is reasonably expected to cause “damage” to national security if disclosed.

What kinds of things are Top Secret?

The former CIA officer David Priess, who is now publisher of the website Lawfare, said on “New Day” that no matter the specific classification, it’s information the government has an interest in not being made public.

It could be intelligence gathered on the North Korean nuclear program or Russian military operations, for example.

Leaks can be disastrous or deadly

The government often gets this type of information by asking people to risk their lives or usingtechnology it doesn’t want adversaries to know about.

Talking about it on Monday morning, Priess became emotional.

“Exposing this information put people’s lives at risk,” he said. “That’s not a joke. We know people who have died serving their country this way.”

What took so long?

The larger question than what’s classified, Priess argued, is why, if the government knew the documents were at Mar-a-Lago, it took investigators so long to go get them.

In order for a president to declassify anything, he argued, there still needs to be a paper trail so everyone knows something is declassified.

“If they’re not marked declassified and other documents with the same information aren’t also declassified, did it really happen? If there’s no record of it, how do you even know?”

We may not know more for a very long time

The problem now may be that imaginations will run wild about what is in the documents.

It could be a very long time before American voters have any idea what this was all really about.

“Technically we won’t see any further action on this case on the legal docket unless and until DOJ brings criminal charges against any person,” said CNN legal analyst and former federal prosecutor Elie Honig, also on “New Day.”

RELATED: DOJ opposes making public details in Mar-a-Lago search warrant’s probable cause affidavit

Already there is some speculation that rather than pursuecharges, the government was simply trying to secure the data.

Classified information can stay that way for years and years – between 10 and 25, according to the declassification guidelines signed by Obama.

The standard is that if something no longer needs to be classified, it should be declassified. And if it needs to be classified past that 25-year period, it can be.

Look at the Top Secret documents of yore

The FBI, CIA and State Department all have online reading rooms of previously classified data released through the Freedom of Information Act. None of it is very recent stuff.

The case of Trump’s Mar-a-Lago documents seems special, however, and there are already bipartisan calls from Sens. Mark Warner and Marco Rubio – the top elected officials on the Senate Intelligence Committee – to Director of National Intelligence Avril Haines and Attorney General Merrick Garland asking for more information about what was taken by the FBI.

Examples of prosecutions

Prosecutions for mishandling of classified data can involvehigh-profile figures.

For example, retired general and former CIA Director David Petraeus gave classified information to his mistress, who was writing a book about him. He ultimately pleaded guilty, paid a $100,000 fine and got two years of probation.

What data did he mishandle? From CNN’s report at the time: During his time as commander in Afghanistan, Petraeus kept personal notes including classified information in eight 5-by-8 inch black notebooks. The classified information (included)identity of covert officers, war strategy, notes from diplomatic and national security meetings and security code words.

Other figures are not as familiar – like Asia Janay Lavarello, a civilian Defense Department employee working in the US Embassy in Manila, who took classified documents to her hotel room and her house while she was working on a thesis project. She got three months in prison.