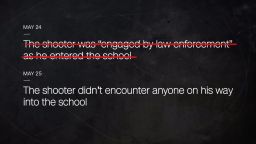

As details about failures of the police response to the school massacre in Uvalde, Texas, have trickled out through leaks and incomplete official reviews, it’s still not clear more than two months later to what extent any of the agencies involved are investigating individual and systemic mistakes in the response to the most deadly US campus shooting in nearly a decade.

Residents, policing experts, other law enforcement officials, state leaders and lawmakers all have criticized police from more than 20 agencies on scene that day for the delay in confronting a spree shooter who was in classrooms at Robb Elementary for more than an hour with 21 people he fatally shot and 17 others injured.

Officials representing agencies involved in the immediate response largely have avoided talking about their internal investigations – if acknowledging them at all – including whether their goals include discipline for officers or others, or a focus on how similar incidents could be handled better, or both. Also not entirely clear are steps they may be taking to minimize potential bias as they investigate themselves.

Officials with the city of Uvalde and the state of Texas since mid-July have said they’re reviewing their police departments in light of the May 24 mass killing, with the city placing its acting chief that day on leave. School district officials have put the chief of their own separate police department on leave as they consider firing him and briefly suspended the Robb Elementary principal.

Still, frustration and anger have mounted in this grieving community. With the gunman dead at the hands of law enforcement – albeit after 77 minutes in the school – getting a full and true picture of what happened that day, along with consequences for police, are seen as tangible vehicles to justice in the face of so much lost life.

At Uvalde school district and city council meetings this week, community members again pressed their elected officials on why officers at the school that day haven’t been relegated to desk duty or fired. The school district superintendent also was asked why he had not sought an independent investigation into the tragedy, and the mayor was pressed on how and why the city chose an Austin, Texas, investigator to lead its internal review.

“We have yet, almost three months later, to hear any answers or to see any accountability from anybody at any level – from law enforcement officers, to campus staff, to central office and beyond,” Uvalde resident Diana Olvedo-Karau told the school board. “And we just don’t understand why. I mean, how can we lose 19 children and two teachers tragically, just horribly, and not have anybody yet be accountable.”

“It’s approaching three months, and we are still being placated with tidbits or being outright stonewalled or being given excuses” about the city police department’s response, said resident Michele Prouty, who passed out complaint forms against Uvalde police at Tuesday’s city council meeting. “What we have instead – what we are traumatized again and again by – is an inept, unstructured national embarrassment of a circus tent full of smug clowns. These clowns continue to cruise our streets sporting their tarnished badges.”

A looming US Department of Justice after-action report has perhaps the strongest chance of giving a clear understanding of how the day’s horrific events unfolded, experts who spoke to CNN said. Such reports tend to home in on opportunities for improvement, while discipline typically must be backed by precise allegations that would hold up if challenged by an officer or subject to court hearings or arbitration processes.

But it’s not clear precisely what parameters those who are overseeing reviews of the city and school district police departments are using to identify systemic failures or root out findings that could lead to discipline for officers.

The Texas Department of Public Safety has said its wide-ranging internal review could result in referrals to an inspector general. The agency also is conducting the criminal investigation into the Uvalde massacre itself – probing details such as how the shooter got his guns and his online communications before the attack – separate from the internal review of its officers’ conduct at Robb Elementary. Part of that work, it has said, is “examining the actions of every member of (a) law enforcement agency that day.” But it’s not clear whether officers are cooperating with the inquiry.

The district attorney reviewing the criminal investigation, Christina Mitchell Busbee, said she would “seek an indictment on a law enforcement officer for a criminal offense, when appropriate, under the laws of Texas.” But it’s not clear under what law any officer might be charged or whether evidence so far supports charges.

Meantime, how Texas DPS has cast its own role in the tragedy already has come under scrutiny. Its officers were at Robb Elementary earlier than previously known – and longer than Texas DPS has publicly acknowledged – materials reviewed by CNN show, with at least one DPS trooper seen running toward the school, taking cover behind a vehicle and then running toward an entrance within 2-1/2 minutes of the shooter entering. The agency’s director instead publicly has focused on when the first DPS agent entered the hallway where classrooms were under attack.

Further, a Texas DPS spokesperson who made three phone calls to a DPS sergeant inside the school during the 70-plus minutes officers waited to confront the gunman later gave journalists a narrative that quickly unraveled. Since then, news organizations, including CNN, have sued the Texas DPS for access to public records related to the massacre.

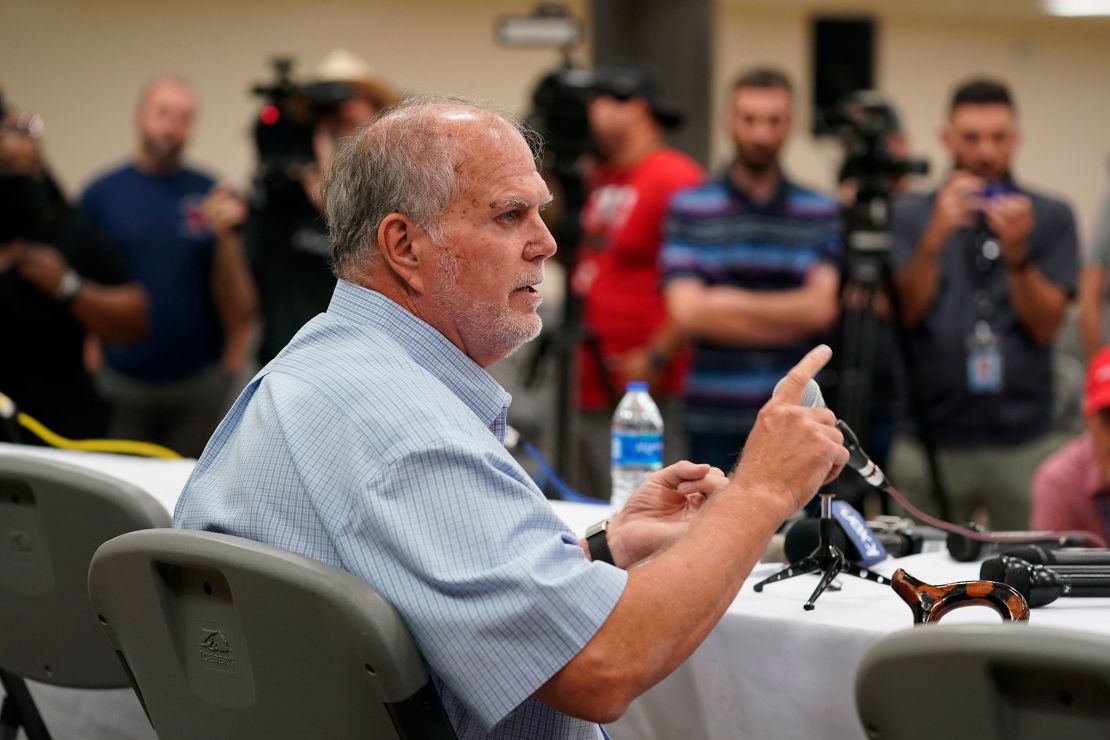

Amid the inconsistencies, the head of the state’s largest police union, along with a senior state lawmaker, have questioned Texas DPS’s ability to investigate itself. “I don’t know that we can trust them to do an internal investigation,” Charley Wilkison, executive director of the Combined Law Enforcement Associations of Texas, told CNN.

“It would be best if the investigation were headed up by an outside independent source that the public can have total confidence in,” said Wilkison, whose union represents law enforcement officers across the state, including some in Uvalde.

So far, three ranking public officials have been placed on leave over the botched emergency response to the shooting:

• Mariano Pargas, the Uvalde Police Department lieutenant who served as acting chief of the city’s police force on the day of the fatal shootings, was put on administrative leave with pay in mid-July while it’s determined whether he should have assumed command, and each of the 25 officers in the city department who responded that day is under investigation, officials have said. Pargas is the only city employee on leave following the massacre, the mayor told CNN on Tuesday. Pargas has not responded publicly to the claim, including requests this week from CNN.

• Pete Arredondo, chief of the school district’s five-person police department at the time of the massacre, was placed on unpaid leave, with the district considering whether to fire him. Two state reports – one an investigative report by a Texas House of Representatives committee and the other by a police training center based at a public university – faulted the law enforcement response, with Arredondo as the ranking officer at the scene; he’s said he did not see himself as incident commander. His leave began June 22, and school officials have not commented on the status of the other officers who were there that day.

• Mandy Gutierrez, the school’s principal, was suspended with pay in late July after the legislative panel found the school had a “culture of noncompliance” with safety policies to keep doors locked at all times. She has disputed this assessment. After three days, the district reinstated Gutierrez as principal. Roughly a week after that, Gutierrez accepted a new role as the Uvalde school district’s assistant director of special education.

City reveals its probe after scathing legislative report

The Texas state House report released July 17 showed a complete breakdown in the “chaotic” law enforcement response to the shooting, describing police actions that day as “lackadaisical,” with “obvious deficiencies of command and control” and with heavy reliance on “inaccurate information.”

The report identified 23 agencies that had personnel at the scene, with Uvalde city and school district police among the first to arrive. Among those Uvalde Police Department officers who waited for direction and resources were two sergeants with a combined 320 hours of SWAT training during their shared 33 years in law enforcement, state records show. The sergeants, including the department’s SWAT commander, had also received active shooter training.

Despite that heavy presence, the first public mention of an investigation into police action by the city of Uvalde didn’t come until hours after the legislative report dropped. The revelation was made July 17 as the city announced it had put Pargas on leave and Uvalde Mayor Don McLaughlin released body-worn camera footage from seven officers who responded to the school. (Even nearly two months after the killing spree and as his furious constituents had packed public meetings to demand accountability for the dead fourth-graders and their teachers, the mayor cast the video release as a model of transparency he achieved after struggling with city attorneys who he said for legal reasons wanted to keep the tapes private).

It’s not clear whether any internal city investigation was underway between the May 24 massacre and the announcement of the internal investigation, though best practices for investigations dictate they usually begin as close to the incident as possible.

Then at a July 26 city council meeting, city officials said they’d hired the firm of Jesse Prado, a former Austin police homicide detective, to lead their review. Council members said their investigator should finish his work within two months, then Prado will make recommendations – possibly including disciplinary actions – to the council.

“If there’s any officer that’s in violation of any policy or procedure that they needed to act on and did not and might have caused these children to die, these teachers to die, I can assure you, heads are going to roll,” Uvalde City Councilmember Hector Luevano said during the session. Prado declined to comment for this story.

City officials, meantime, have refused for nearly two weeks to answer questions about their review of officers’ actions that day. Tarski Law, listed on the city council’s website as city attorney, also declined to comment and referred questions to Gina Eisenberg, president of a public relations firm that specializes in “crisis communications” and was hired by the city to field media requests. Eisenberg said the city would not comment. McLaughlin, the mayor, said Tuesday he couldn’t characterize the city’s relationship with Eisenberg, who hired her or who is paying her bill, saying, “I don’t know anything about her. I have nothing to do with it.”

Eisenberg also declined to answer questions about the city police department review process. McLaughlin was certain such a process existed but wasn’t aware of related procedures, he told CNN on Tuesday. The internal investigation led by Prado was launched August 1, Eisenberg said. The city attorney chose Prado for the job without a bidding process and based on word-of-mouth recommendations, the mayor told CNN; Tarski Law referred CNN to Eisenberg, who wouldn’t provide a copy of its contract with Prado’s firm, explain what the department’s internal affairs process was before the shooting or say whether that process was used at any time before Prado was hired. Eisenberg said the city would not release further information or comment.

The full scope of Prado’s investigation also isn’t clear – whether he’s conducting an after-action review meant to identify failures for future understanding or investigating specific allegations of broken rules in response to internal complaints, or some hybrid. Prado will have “free range to take the investigation wherever the investigation takes him,” McLaughlin told CNN on Tuesday. While it’s unlikely Prado’s source materials will be released, the mayor said, he vowed to make Prado’s report public after first sharing it with victims’ families – “if I have any say in it.”

“When we see that report, whatever it tells us we need to do and changes we need to make – if it tells us we need to let people go or whatever it tells us – then that’s what we will do,” McLaughlin told CNN.

With 25 officers under investigation, it’s not clear if Prado’s firm alone is capable of handling such a wide-ranging investigation. He’s listed as the owner/investigator of the firm and is the only investigator listed at its website. Eisenberg wouldn’t say what evidence, videos and statements will be made available to Prado or if he will have the power to interview officers, adding the city would not release further information or comment.

The city has released all the body-worn camera video it has, McLaughlin told CNN on Tuesday, leaving unclear whether its other 18 responding officers wore cameras that day or turned them on. The mayor wasn’t sure if any city police dash-mounted cameras captured the law enforcement response, he said. The released videos were edited to remove hallway footage when Border Patrol agents entered the classroom, and it’s not clear whether they were edited to remove footage at the beginning that may shed more light on what officers knew as they approached the building. Eisenberg said the city would not release further information or comment.

The mayor met with families in early August to talk about the internal review. Meanwhile, on the streets of this city of about 15,000, some residents – for the first time in their lives – fear those sworn to protect them.

“This is my home and I want to die here. But I feel uncomfortable when I see a police officer,” said Uvalde native Matty Myers before Tuesday’s city council session. “They need to be accountable. You guys need to do something as soon as possible so that we can feel secure and safe here in our home in Uvalde.”

Top school district leaders put on leave

As Arredondo, who’s said he did not consider himself the incident commander at the massacre scene, remains on unpaid leave – with his termination or resignation possible – it’s not clear whether the separate school district police department’s four other officers have been subject to any internal review. Two school board hearings to consider firing Arredondo have been delayed: on July 23, then August 4 “due to a scheduling conflict,” according to the school district. Three future dates have been proffered to Arredondo’s attorney, Superintendent Hal Harrell said during Monday’s school board meeting.

Still, anger overflowed at the meeting as Arredondo’s fate was discussed, with one woman shouting, “I don’t want him to walk away with a penny.”

“We’re doing it right … to make sure that when it’s done, it’s done correctly and there’s nothing that’s going to come back and bite us back later,” replied Luis Fernandez, the school board president. The police department run by the Uvalde Consolidated Independent School District is overseen by the seven-member elected school board and is separate from the city’s police department, which is overseen by Uvalde city government.

Arredondo was elected to the Uvalde City Council weeks before the massacre but resigned from that panel about a month after the mass killing, writing he wanted “to minimize further distractions.” Other school district officers who were at Robb Elementary that day have been seen back at work, including providing security at school board meetings. Some parents have asked them how, if they were at the scene of the deadly attack, they could be trusted again.

Asked Monday if he’d considered an independent investigation into the school district police department’s response to the mass shooting, Harrell, the district’s top executive, said: “I have not, but I’ll look into that.”

Whether any other educational staff besides Gutierrez, the principal, were investigated or placed on leave also is unclear. District officials didn’t respond to requests for comment. In responding to the gunfire, Gutierrez believes she “followed the training that I was provided to the best of my abilities,” she told CNN in an exclusive interview. “And I will second-guess myself for the rest of my life.”

But Javier Cazares, whose daughter was killed inside Robb Elementary, called the principal’s reinstatement a “slap in the face.” Cazares’ daughter, Jacklyn Cazares, was 9 years old. “Being the person in charge, she should’ve made sure that school was safe, and she failed at her job – bottom line. It goes to show you how Uvalde works: They will do anything to protect themselves and forget the children,” Cazares told CNN in late July. “No one wants to be responsible for their actions and inaction, and it makes me sick.”

Uvalde school officials during Monday’s tense, two-hour school board meeting detailed efforts to improve security across the school district. The plan includes hiring an interim police chief to audit the department and assigning 33 Texas DPS troopers, Harrell said.

But for at least one parent, more police is not the answer.

“I told my son that we are going to have extra cops there, you know, and he said, ‘But who cares about the cops? They are not going to do anything anyway. They are not going to go in anyway,’” Adam Martinez told the board. “That’s the children speaking to y’all. And I would expect somebody to try and change that perception.”

After the meeting, Fernandez said he had to check with legal counsel before answering any more questions from CNN. Harrell referred any questions to the school district’s communications director, who asked CNN to resend questions by email; she did not immediately respond.

Trust erodes in state law enforcement agency

The day after the release of the state House report and the city of Uvalde’s body-worn camera footage, Texas DPS announced that the prior week it had launched an internal review into the police response in Uvalde. An internal committee would review the “actions of every DPS Trooper, Officer, Agent and Ranger,” an agency spokesperson said, declining to answer questions about it.

The department’s internal review would precede any potential referrals of officers to an inspector general, DPS Director Col. Steven McCraw added August 4. “Every one of our officers will undergo scrutiny by the DA and an internal investigation. Just because they didn’t violate the law, doesn’t mean they acted appropriately based on our policy,” he testified during a hearing about the release of records.

However, inconsistencies in the agency’s own telling of its officers’ role at Robb Elementary have already cast doubt over whatever the review might conclude. Information about the Texas DPS response also has been sought from the agency by the FBI under a public records law typically used by reporters and citizens. It’s not clear why the FBI went through that process, and the agency declined to comment. CNN got a copy of the FBI’s inquiry through a records request.

One example of conflicting facts from Texas DPS involves body-worn camera footage released by Uvalde city officials. It appears to show at least one DPS trooper in the first wave of officers who approached the school – minutes earlier than Texas DPS officials had publicly acknowledged.

Until early August, McCraw had only reported – in testimony before the state Senate and in written timelines released by his office – a trooper first entered the school at 11:42 a.m., about nine minutes after the shooter walked in. But the body-worn camera footage shows a DPS trooper already at the building’s west entrance about five minutes earlier. And other footage shows another trooper outside the school more than two minutes before that, taking cover behind a vehicle and then running toward an entrance.

Texas state Sen. Roland Gutierrez even before those details came to light had questioned Texas DPS’s ability to investigate itself. “DPS has trafficked in misinformation and prevented the disclosure of public information to Uvalde families. Can Texans trust this state agency to investigate itself? I surely cannot,” Gutierrez, who is not related to the principal, wrote July 19 to the lieutenant governor.

Further, a Texas DPS spokesperson who during the siege had three phone calls with an agency supervisor inside the school gave a public accounting of the police response the next day praising law enforcement. But the story soon fell apart amid reporters’ scrutiny and outrage from parents and relatives of the victims. The supervisor, among the first wave of police to arrive at Robb Elementary, had three phone calls with Lt. Christopher Olivarez in the more than 70 minutes after law enforcement arrived but before they killed the shooter, call logs later obtained by CNN show.

The logs show Olivarez called the supervisor at noon, 12:13 p.m., and 12:18 p.m. on May 24 but do not reveal the duration or content of each call. Olivarez went on to tell reporters the gunman was killed by officers who “place(d) their own lives between the shooter and those children to try and prevent any further loss of life” and said an officer was shot while entering the classroom in which the shooter had barricaded himself.

Conflicting details soon emerged, however, confirming officers never appeared to have tried to open the door of the classroom while waiting in the hallway for more than an hour. The House investigative report cast doubt on whether the door ever was locked, citing apparent common knowledge the lock didn’t work. The House report also noted the shooter fired on officers as they entered but not that any were shot.

Still, Texas DPS spokesperson Travis Considine insisted in late July to CNN that McCraw’s testimony about when a trooper entered the school hallway was accurate and “our internal committee is currently reviewing whether or not those individuals violated any department policies or doctrine.” The agency declined to respond to repeated questions about the phone calls between Olivarez and the supervisor.

While it’s unclear when any of the reviews of law enforcement’s response to the Uvalde massacre will wrap up, the Texas DPS probe – like the others – could have implications for its own and other officers, raising the stakes for how impartially and transparently it’s handled. As with the other probes, too, how it’s conducted and what it concludes will impact what closure families of the slain in this small, tortured city can receive.

Texas DPS “was fast to wash its hands, to point fingers and to make sure that the general public, particularly the elected officials, knew that they were spotless, blameless and that this was a local problem,” said Wilkison, the police union chief. “No one created this environment, (in) which everyone’s to blame except DPS. No one did that except them. If we’re to never, ever let this happen in Texas, we have to know what happened, exactly what happened.”

And so as a new school year is set to start September 6 in Uvalde – with Robb Elementary students at different sites – this community continues to scrutinize Texas DPS and to pack school board and city council meetings to decry the dearth of formal consequences for officers or agencies that responded to the May slaughter. Speaking to the school board this week, Olvedo-Karau said: “We have dead children and no accountability.”

CNN’s Stella Chan, Matthew Friedman, Jeremy Harlan and Rosalina Nieves contributed to this report.