Editor’s Note: Peter Bergen is CNN’s national security analyst, a vice president at New America and a professor of practice at Arizona State University. Bergen’s new paperback is “The Rise and fall of Osama bin Laden.” from which this article is, in part, adapted. The views expressed in this commentary are his own. View more opinion on CNN.

In 1961, after a CIA-backed invasion of Cuba failed spectacularly, President John F. Kennedy said of the Bay of Pigs fiasco, “Victory has 100 fathers and defeat is an orphan.”

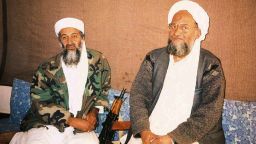

Last week, President Joe Biden took a victory lap when he announced that the US had tracked down and killed its most wanted terrorist, al Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri, who was living in a house in Kabul, Afghanistan. Don’t expect a similar celebration on August 30, the first anniversary of the US troop withdrawal from Afghanistan, which ended the longest war in American history. Any realistic assessment of that action shows that it will long be seen as a defeat rather than a victory – and it’s likely no one will own up to the responsibility for the decision.

The US launched a war against Afghanistan in 2001 after the Taliban regime harbored Osama bin Laden, giving him the ability to plot and carry out the 9/11 terrorist attacks which killed almost 3,000 Americans.

As US and NATO troops battled Taliban and al Qaeda forces, the new US-backed government in Kabul also presided over two decades of progress in Afghanistan. To be sure, Afghanistan wasn’t Norway, but it was becoming a somewhat functional, democratizing Central Asian state that saw striking progress in reducing child mortality and increasing life expectancy, one that provided jobs for women and education for millions of girls; it nurtured scores of independent media outlets, and held regular, if flawed, presidential elections.

All of that changed when the US began withdrawing and the Taliban took over the entire country on August 15, 2021. Women’s rights evaporated. They have no right to work, except in a narrow set of female-related jobs such as cleaning women’s toilets in Kabul; when they travel distances of more than 45 miles they must be accompanied by a male relative, and the Taliban have ordered women to stay at home and to cover themselves completely should they ever venture out. Their male relatives will be punished by the Taliban if women don’t follow these directives. Girls do not have the right to be educated after the age of 12.

On the Taliban’s management of Afghanistan, one data point suffices to underline the group’s gross incompetence: Around half of the Afghan population are today “facing acute hunger,” according to the UN.

On the Taliban’s respect for other ethnic Afghan groups: There is no evidence that the Taliban are creating an “inclusive” government as their leaders claimed they would. Pashtuns make up almost all the leadership of the Taliban, while other ethnic groups in Afghanistan such as the Hazaras, Tajiks and Uzbeks are almost entirely excluded from leadership roles.

On their respect for democracy: The Taliban, conveniently, don’t believe in elections. Instead, they are a theocracy; their leader is known as the “Commander of the Faithful,” a title that claims he is the leader of all Muslims. In the past year under Taliban rule, 40% of Afghanistan’s independent media outlets have closed.

On the Taliban’s alliance with al Qaeda: Well, last week’s news made clear the relationship is thriving. The fact that the leader of al Qaeda, Ayman al-Zawahiri was living in downtown Kabul for months – with what the Biden administration describes as the awareness of some Taliban officials – speaks for itself. Zawahiri was killed late last month in a US drone strike.

After the news broke that Zawahiri had been hiding in Kabul, Lisa Curtis, the top official at the White House for Afghanistan during the Trump administration, tweeted “#Taliban basically asserting Doha agreement allows them to shelter #AlQaeda. Proves it was the worst agreement in US history. Not worth the paper on which it’s written.” This was a particularly damning assessment coming from a senior American official who was working on Afghanistan while the Doha agreement between the US and the Taliban was being negotiated.

One of the most powerful men in Afghanistan today is the acting Minister of Interior, Sirajuddin Haqqani, who has ties to al Qaeda, according to a United Nations report that said he is “assessed to be a member of the wider Al-Qaida leadership, but not of the Al-Qaida core leadership.”

A February 2020 opinion piece in The New York Times with Haqqani’s byline blandly identified him only as “the deputy leader of the Taliban.” What the Times didn’t tell its readers is that Haqqani was also on the FBI’s most wanted list and that his men had kidnapped a reporter for … The New York Times.

This op-ed featured ludicrous lies including, “We together will find a way to build an Islamic system in which all Afghans have equal rights, where the rights of women that are granted by Islam – from the right to education to the right to work – are protected” and “reports about foreign [terrorist] groups in Afghanistan are politically motivated exaggerations by the warmongering players on all sides of the war.”

How it happened

The US pullout from Afghanistan a year ago was orchestrated by a successive series of decisions by former President Donald Trump, President Joe Biden and the chief US negotiator with the Taliban, Ambassador Zalmay Khalilzad. None of these men are ever likely to fully acknowledge their paternity of the debacle that unfolded in Afghanistan, which followed the worst diplomatic agreement in US history that enabled the Taliban to win at the negotiating table in Doha, Qatar what they could never win on the battlefield.

Khalilzad has defended the deal saying, “The negotiation was a result of–based on the judgment that we weren’t winning the war and therefore time was not on our side and better to make a deal sooner than later.”

By the end of the Trump administration, the fledgling Afghan state was supported by only some 2,500 US troops, a tiny fraction of the more than two million men and women in the active-duty US military, reserves, and National Guard units. Assisted by 9,000 allied, mostly NATO troops and 18,000 contractors this small US force was enough to enable the Afghan military to fend off the Taliban, which was never able to capture and hold any of Afghanistan’s 34 provincial capitals before Biden announced the total American withdrawal in April 2021.

Why Biden went through with the withdrawal plan that he had inherited from Trump is still something of a puzzle since there was no large, vocal constituency in the Democratic Party that was demanding a total US pullout from Afghanistan, and Biden’s top military advisers had clearly warned him of the risks of doing so.

In public testimony before the US Senate Armed Services Committee, US Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. Mark Milley and US CENTCOM commander Gen. Kenneth McKenzie, said they had advised the Biden administration that unless the US kept around 2,500 troops in Afghanistan, the Afghan military would collapse. Collapse it did.

The “Taliban 2.0” delusion

The publication of Haqqani’s op-ed in The New York Times was emblematic of the wishful thinking about the Taliban in the US that had persisted for years. In this view the Taliban were just a bunch of misunderstood backwoodsmen who would eventually do what was only sensible: break with al Qaeda and abandon much of their misogynistic ideology as a quid pro quo for their recognition on the world stage.

This was a classic case of mirror imaging; the belief that the Taliban would do the rational things some gullible Americans expected them to do, as opposed to implementing the quasi-mediaeval ideology that has been at the core of their armed movement since they first emerged almost three decades ago. It was like imagining the Khmer Rouge would “mature” once they had taken power in Cambodia.

A key proponent of the view that the Taliban would change if the right carrots were dangled in front of them was Barnett Rubin of NYU, an expert on Afghanistan, who claimed in a paper that he published with the United States Institute of Peace in March 2021 that the US had “underestimated the leverage that the Taliban’s quest for sanctions relief, recognition and international assistance provides.”

Turns out that it was Rubin who overestimated how much the Taliban cared about sanctions relief and international assistance, while he had also vastly underestimated their desire to banish women from jobs and education and maintain their warm relations with their old buddies in al Qaeda. This shouldn’t have come as much of a surprise, since that was exactly how the Taliban had ruled the last time that they were in power in the years before 9/11. The Taliban hadn’t fought the US and Afghan militaries for two decades only to install a quasi-democracy when they came to power for the second time.

The “moderate” Taliban 2.0 that was supposedly emerging in recent years was a profound delusion that gripped US policymakers.

A month after Biden had announced the impending withdrawal of all US troops from Afghanistan, the US negotiator with the Taliban, Khalilzad, testified to the US House Foreign Affairs Committee on May 16, 2021, that those who thought the Taliban would quickly take over the country as the US pulled out were “mistaken.” Khalilzad also asserted that the Taliban would opt for a political settlement over a military victory, testifying, “They say they seek normalcy in terms of relations — acceptability, removal from sanctions, not to remain a pariah.”

Just months later the distinctive white flags of the Taliban were fluttering over the capital, Kabul, and the Taliban began implementing their theocratic state. In a symbolic move the Taliban’s feared religious police soon commandeered what had formerly been the ministry for women’s affairs. Obviously, that ministry would no longer be needed, but the “Vice and Virtue” police would have to be properly accommodated.

The United Nations released a report in May in which it observed that an astonishing 41 members of the Taliban serving in the cabinet or other senior-level government positions in Afghanistan are on UN sanctions lists.

Taliban 2.0 was a mirage, and the Taliban today is Taliban 1.0 with one major difference; they are far better armed than the Taliban that ruled over most of Afghanistan from 1996 to 2001. Now they ride into battle with American armored vehicles and M-16 rifles that were left behind as the US military rushed for the exits last summer. The Taliban today also face a far weaker opposition movement in Afghanistan than was the case for the pre-9/11 Taliban.

Signaling weakness to Russia and China

When Biden spoke to the American people on Aug. 31, 2021, as the last US soldiers departed Afghanistan, he framed the withdrawal as a way of positioning the US to compete better against great-power rivals, saying, “We’re engaged in a serious competition with China. We’re dealing with the challenges on multiple fronts with Russia…And there’s nothing China or Russia would rather have, would want more in this competition than the United States to be bogged down another decade in Afghanistan.”

This was an absurd rationale: For years both China and Russia had hoped to push American forces out of Afghanistan because the country borders both China and the republics of the former Soviet Union. Russia had covertly supported the Taliban, according to the US military, while the Chinese had drawn closer to the Taliban in recent years.

As they pulled out of Afghanistan, the Americans abandoned the vast Bagram Air Base which could house up to 10,000 troops; a more ideal site from which to engage in competition with either China or Russia is hard to imagine.

You could practically hear the high fives in the Kremlin as the US ignominiously retreated from Afghanistan, which seemed to herald an era of the US pulling back from the world.

It hardly seems accidental that three months later Russian President Vladimir Putin moved an army to the border with Ukraine as a prelude to his invasion of the country.

A predictable fiasco

In June 2021, I wrote for CNN, “We could see in Afghanistan a remix of the disastrous US pullout from Saigon in 1975 and the summer of 2014 in Iraq when ISIS took over much of the country following the US pullout from the country.”

That prediction, unfortunately, proved to be accurate; the American pullout from Saigon looked like a dignified retreat compared to the scenes of thousands of desperate Afghans trying to get on planes leaving Kabul airport last August. Some Afghans were so desperate to leave that they clung to the fuselage of a plane that was taking off – and two plunged to their deaths. On Aug. 25, 2021, 13 US soldiers and at least 170 Afghans were killed at the airport by a suicide bomber dispatched by the Afghan branch of ISIS. And the Taliban took over the entire country even before the last US soldiers had left Afghanistan.

Compounding Biden’s disastrous policy decision to completely pull out of Afghanistan was the botched handling of the withdrawal. According to a report about that withdrawal released in February by Republican senators sitting on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, the first White House meeting to discuss evacuating Americans and Afghans from Afghanistan took place on Aug. 14, only one day before the Taliban seized Kabul and five months after Biden had first publicly announced the total US withdrawal from the country.

Biden patted himself on the back that the US military subsequently extracted 124,000 Afghans from Afghanistan, calling the operation an “extraordinary success,” which was like an arsonist praising himself for helping to try to put out a fire that he had started.

But even accepting the most self-congratulatory view of the Biden administration’s handling of the withdrawal, the vast majority of the Afghans who had worked with the US were abandoned. The Association of Wartime Allies, an advocacy group for Afghans who had worked for the US, estimated in March that only about 3% of the 81,000 Afghans who had worked for the US government and had applied for special visas had made it out of Afghanistan, leaving 78,000 behind.

Four months after the Taliban took over Afghanistan, the Biden administration convened the “Summit for Democracy” in Washington consisting of the world’s democracies. Five months earlier Afghanistan would have warranted an invitation to this summit, but Biden had enabled the Taliban to take over the country, which ended almost every shred of a liberal democracy that had once existed there.

Following the Afghan debacle, Biden’s favorable ratings dropped to the lowest level of his presidency to that point to 46%. They have never recovered.

The Biden administration now faces a policy dilemma of its own making. Since so many millions of Afghans are on the brink of starvation, Biden officials cannot completely turn their backs on Afghanistan. And yet, it’s hard to help Afghans without propping up the Taliban in some manner. The Biden administration has tried to ensure that all US aid to Afghanistan is administered in a way that it doesn’t end up in the hands of the Taliban, but realistically any help that the US sends to Afghanistan tends to help the Taliban remain in power.

This is surely one of the most spectacular own goals the US has ever scored.