A drug is available for monkeypox patients who have or who are at risk of severe disease, but doctors say they continue to face challenges getting access to it.

The US Food and Drug Administration hasn’t approved tecovirimat – sold under the brand name Tpoxx – specifically for use against monkeypox, but the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has made the drug available from the Strategic National Stockpile through expanded access during the global outbreak that has caused about 5,800 probable or confirmed cases in the US.

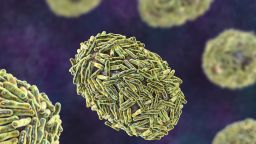

Tpoxx was FDA-approved in 2018 as the first drug to treat smallpox, a virus in the same family as monkeypox. The World Health Organization declared smallpox eradicated in 1980, but concerns that the virus could be weaponized drove the US government to stockpile more than 1.7 million courses of the drug in case of a bioterrorism event. Tpoxx is approved in the European Union to treat monkeypox as well as smallpox.

It can be taken intravenously or more commonly as an oral pill.

Tpoxx is considered experimental when it comes to monkeypox treatment because there’s no data to prove its effectiveness against the disease in humans. Its safety was assessed in healthy humans before its FDA approval for smallpox, and its effectiveness has been tested in animals infected with viruses related to smallpox, including monkeypox.

As the ongoing outbreak increases demand for the drug, the FDA and CDC recently eased some of the administrative requirements that health care providers face when requesting access.

However, doctors across the country suggest that significant barriers remain, causing some patients to wait days for shipments or travel to find medical centers that can provide the product at all.

“Patients are trying hard to get this medication, even going out of city or out of state in some cases,” said Dr. Peter Chin-Hong, an infectious disease physician at UCSF Health. His hospital has fielded calls from patients throughout California as well as from Colorado and even Canada and the UK, all hoping to get treatment.

Health agencies cut red tape, but challenges persist

The CDC says doctors may want to use Tpoxx for people who have monkeypox symptoms in particularly hazardous areas like the eyes, mouth, genitals or anus. It may also be used in people with severe symptoms like sepsis or brain inflammation, or in people at high risk of severe illness, including those with weakened immune systems because of conditions like HIV/AIDS, those with skin conditions like eczema, children, pregnant women and people with other complications like a bacterial skin infection.

Many people who have gotten sick during the outbreak have had mild symptoms and have recovered without treatment, but some doctors say they’ve seen more patients with severe disease than they expected.

Dr. Mary Foote, medical director of the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, said in late July that about 20% to 25% of patients there have met the criteria for Tpoxx. As of July 23, the treatment had been prescribed for about 215 out of 839 confirmed cases.

“Anecdotally, of the providers that we’ve spoken to, we’ve seen, very commonly, significant improvements within just a few days of starting and improvements in pain. And very significantly, we have not seen any significant adverse events reported and very few even mild adverse events. Some headaches, nausea. But that’s pretty much it,” Foote said.

However, it’s unclear what proportion of the more than 5,000 probable or confirmed cases nationwide have been treated with Tpoxx. CDC officials said in a webinar that more than 223 people had been treated as of July 22, but the agency did not respond to requests for a more specific number.

Experts say the number who’ve been treated is probably a fraction of those eligible.

“I think a majority of patients don’t have access,” Chin-Hong said. He’s seen firsthand how hard it can be to get the drug.

Chin-Hong treated Kevin Kwong, 34, after he developed painful lesions all over his hands, feet and face that spread to his back, thighs and scalp.

“There were moments I could barely swallow food because of the sores in the back of my throat,” Kwong said. Lesions near his eye threatenedto have long-term effects on his vision.

But after his symptoms began, it took about five days for Kwong to get to a facility where he could get Tpoxx. He spent four days doing telehealth visits and going to urgent cares and emergency rooms as his rash worsened before doctors finally suspected monkeypox – and even then, he says, they didn’t know how to treat him and sent him home.

But his symptoms only got worse, and he went back to the ER before being advised to go to the UCSF Medical Center because it was treating monkeypox patients. Exhausted and frustrated, he agreed out of desperation. He got there in the middle of the night; several hours later, he met Chin-Hong and took his first dose of Tpoxx.

“He had to push through and get to a county that has Tpoxx and go to the emergency room in the hospital he knew might offer him therapy because the place where he comes from doesn’t have therapy,” Chin-Hong said. “If he didn’t advocate for himself, he would have never gotten Tpoxx.”

To get Tpoxx, a patient must sign a consent form from the CDC, and doctors must request access from the CDC or their local health department, which involves submitting things like lab tests and consent forms. The CDC and the FDA recently reduced the amount of paperwork needed, made certain tests and photo requirements optional, and allowed health-care workers to start treatment before paperwork is submitted.

“They have made it easier, but it still requires additional time, efforts and resources to be able to prescribe it,” Dr. Jason Zucker, an infectious disease specialist at Columbia University Irving Medical Center.

Chin-Hong says that aside from the paperwork, there’s a high “activation energy” that clinics and hospitals face because the drug is considered experimental for monkeypox and some hospitals and institutions require additional reviews for such treatments. As a result, Tpoxx has been disproportionately used in larger academic medical centers that have better infrastructure for working through such processes.

“We have this interesting situation – and it was like that in Covid too – where a county that doesn’t have Tpoxx will negotiate with another county and the hospital to take the patient if they are still ill and would need Tpoxx. So we may get another patient like that from another county in the East Bay today.” Chin-Hong said of the UCSF Medical Center.

A Pennsylvania man named Adam says it also took him several days to get access to Tpoxx.

Adam had a fever, swollen lymph nodes and body aches, he told CNN Chief Medical Correspondent Dr. Sanjay Gupta. The rashes that characterize monkeypox appeared around his groin, arms, throat and face.

“I would kind of liken it to a crossbreed of Covid, strep throat, mono, kind of all those things together is how monkeypox felt, in addition to the pox, which, that was an experience for sure,” he said.

His doctors were concerned that one lesion under an eyelash could affect his vision.

“He had a lesion on the inside of his lid, but if that would rupture, he would auto-inoculate his eye and could get a keratitis,” said Dr. Stacy Lane of the Central Outreach Wellness Center in Pittsburgh, who treated Adam. She worried that it could put him at risk of blindness.

“By the time I was initially seen and talked about the eyeball, I wasn’t put on the antiviral until almost a week later,” Adam said.

In Adam’s case, his doctor’s office didn’t have Tpoxx on hand, and after putting in the request, it took four days for it to get there from a distribution center.

The Pennsylvania Department of Health said in an email that it typically takes a couple days after a doctor orders Tpoxx for it to get to a health-care provider, since the CDC must first get the product to local public health sites.

“There are different processes in different states and in different hospitals. Every region or every area will have its own problem,” said Dr. Aaron Glatt, chief of infectious diseases at Mount Sinai South Nassau in New York. “If you’re a private physician or your clinic doesn’t have access to Tpoxx immediately, you might have it shipped from the national stockpile, and you have to have a full process – you know, guidelines, shipping itself takes time, filling out the paperwork – so that can take a couple of days.

“In New York City, you’re able to e-prescribe with certain pharmacies that would be able to make sure the appropriate paperwork is filled out to go and have that delivered in a much faster time,” he said.

How clinical trials could help

Irving Medical Center’s Zucker says the process of prescribing Tpoxx involves weighing the risks and benefits for each person. Although some doctors have reported cases in which they think the drug may have been beneficial, the CDC says that evidence of how well it works in humans has been limited to “drug levels in blood” and “a few case studies.”

Tpoxx’s safety was assessed through a study of 359 healthy people before it got FDA approval. Because smallpox has been eradicated since 1980, the drug’s benefits were evaluated through trials on animals that were infected with related viruses including monkeypox virus. There is no human trial data to prove that it’s effective in treating monkeypox.

“Any time that we’re using a new medication, it’s important that we do randomized controlled trials because it’s really the only way to know whether it works,” Zucker said. Randomized controlled trials are studies that evaluate how well a drug works in a group of people who get the drug compared with a group of people who don’t.

Zucker said he’s unsure whether such trials would be ethical in people who qualify for Tpoxx, since some of the participants would get a useless placebo instead.

Dr. Jay Varma, a professor of population health sciences at Weill Cornell Medical College, believes that such trials are ethical in mild cases, people who have been exposed or are at risk of exposure, and children and pregnant women.

“There is a need to get high-quality data about the risks and benefits of Tpoxx,” Varma said.

Zucker said trials would not only help generate much-needed data on how to use Tpoxx, they would help expand access in two ways. First, clinical data could help the drug qualify for a different type of regulatory approval that allows broader access with fewer hurdles. Second, trials could help ease access for people who don’t qualify under the current Expanded Access protocol, such as those with milder disease.

“Historically, antivirals are better earlier than later, but we have to prove it,” Zucker said, adding that there are plans underway for a US monkeypox trial for Tpoxx.

Varma compared the challenges of limited access and clinical data to the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Get CNN Health's weekly newsletter

Sign up here to get The Results Are In with Dr. Sanjay Gupta every Tuesday from the CNN Health team.

“The unfortunate parallel is that the US is behind the UK and Europe in running these trials,” he said.

Lane said she’s hopeful that the CDC and public health departments will continue to work toward better access to the medication. But her expectations are measured.

“Until the FDA approves this for monkeypox or the National Stockpile releases the stockpile for more normal distribution, this is where we’re at,” she said.