The man came to an urgent care clinic in New York with red bumps on his skin in an area where he had a fair amount of hair.

The doctor at the clinic diagnosed the bumps as folliculitis, an infection of the hair follicles. The clinician prescribed antibiotics and sent the man, who is in his 30s, on his way. At home, he continued to help his wife with their five children, one of whom is a newborn.

Despite antibiotics, the bumps spread beyond the first pustules on his groin to his palms, arms, legs and face.

About four days after his initial trip to the doctor, he got a fever and went back to the urgent care clinic for a second look. The doctor at the clinic consulted with Dr. Daniel Griffin, an infectious disease specialist at Columbia University Medical Center, who advised testing for monkeypox.

A few days later, that test came back positive.

“It didn’t seem to set off any alarms, and I think part of that was that this is a happily married man, works in an office. He had no reported risk factors that would have raised someone’s concern, which is unfortunate,” said Griffin, who is now treating the man and got permission to share his story. The man declined to be interviewed.

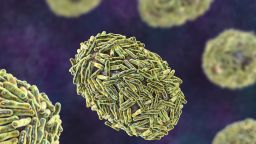

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says that 99% of monkeypox transmission is happening between men who have sex with men, and there’s no doubt that this continues to be a heavily affected community. But some infectious disease experts feel that the focus on this population may be leading clinicians to discount the signs of monkeypox in others.

Monkeypox is not a sexually transmitted disease, but it can spread through the kind of close contact that happens in sexual and other intimate situations. In the United States and other countries, it has exploded among sexually active gay and bisexual men.

At a news briefing Friday, public health officials stressed that few cases have been diagnosed in people outside the community of men who have sex with men, and even those outside cases have been related or adjacent. The first two children in the US who were recently diagnosed with monkeypox, for example, are believed to have contracted their infections through household spread.

Separately, in a call on Saturday to educate doctors about monkeypox, Dr. John Brooks, chief medical officer for the CDC’s monkeypox response, said there had been a case of monkeypox in a pregnant woman in the United States. Monkeypox can cross the placenta during pregnancy and infect babies in the womb. Brooks said the woman had delivered her baby and the child does not appear to have been infected. The baby was given protective antibodies called immunoglobulin as a precaution, and both mom and baby are now doing well, he said.

But that does not represent the majority of cases.

“Actually, 99% of our cases report male-to-male sexual contact,” said Dr. Jennifer McQuiston, deputy director of the CDC’s Division of High Consequence Pathogens and Pathology.

More than 3,500 cases of monkeypox have been diagnosed in the US. CDC officials have said they don’t have detailed demographic information on all those cases.

“There is no evidence to date that we’re seeing this virus spread outside of those populations to any degree,” she added.

‘Our net is not wide enough’

But Griffin says it feels like the earliest days of Covid-19, when it was hard to get a test unless you could show that you had recently traveled to Wuhan, China.

Monkeypox tests are available, and gay and bisexual men are appropriately being considered for testing, but many doctors still aren’t aware of the risk to people outside this population, Griffin said. And that’s despite outreach, webinars and health alerts to clinicians from the CDC.

“I think we’re making a big mistake,” Griffin said. “Monkeypox is probably already outside this target population, and we’re letting it spread because we’re not willing to acknowledge that, because we’re not doing the testing, because our net is not wide enough.”

Other experts agree.

“I’m worried that it has moved beyond this community alone,” said Dr. David Hamer, an infectious disease specialist at Boston University who has been monitoring the monkeypox outbreak in international travelers through his GeoSentinel network of 71 sites around the world.

Hamer said the outbreak seems to have been fueled by three mass gatherings in Europe; at least one was a rave, where people picked up the virus and carried it home. Most of those individuals were gay and bisexual men.

“But there are others who clearly have been infected, including a few young children, and it’s not quite clear how they became exposed,” Hamer said.

One of those cases in the UK was a young child, “and they didn’t understand where and how that child acquired the infection,” he said.

“We need to be thinking more broadly. We need to educate primary care providers” to think about monkeypox if they see someone with a rash, Hamer said.

Modest demand for monkeypox testing

Early the outbreak, doctors were allowed to test for monkeypox only under a narrow set of circumstances because testing capacity was limited to about 6,000 tests a week. Recently, however, the CDC has partnered with five commercial laboratories to scale up testing. When all have their programs running, they’ll be able to process more than 10,000 tests a day and 80,000 tests a week.

Expanding testing to commercial labs makes the process of ordering these diagnostics much easier for doctors, but there’s little indication that much testing is happening outside of sexual health clinics that primarily serve the LGBTQ community.

“Once it hits the commercial labs, we have a much more liberal ability to order these. Nobody is asking us to document any criteria or anything to order the test,” said Dr. Stacy Lane, medical director of Central Outreach Wellness Center, which runs eight health clinics focused on LGBTQ wellness in Pennsylvania and Ohio.

Although many of the commercial labs won’t release the number of monkeypox tests they’re doing, there are indications that test capacity is being underutilized.

A spokesperson for Quest Diagnostics, for example, said in an email that “we’ve experienced modest demand, which continues to grow.”

Dr. Carlos del Rio, an infectious disease specialist at the Emory University School of Medicine, said he didn’t think primary care providers are up to speed.

“We need a lot more information and education to providers about how to use a test and what to do with it,” del Rio said. He added that his own friends and family members were texting him pictures of their rashes, asking if they could be monkeypox.

For the most part, he says, he offers reassurance that what they have probably isn’t monkeypox.

“I think it’s still pretty contained in the community of men who have sex with men,” del Rio said. “It doesn’t mean it’s going to stay there.”

The cost of misdiagnosis

Griffin said his patient has no idea how he was exposed and is now isolated in the basement of his home. People with monkeypox are believed to be contagious for at least four weeks.

He’s taking an antiviral medication called TPOXX, which is being made available to monkeypox patients.

Doctors were able to vaccinate the patient’s wife, and they’re carefully watching his children, including the baby, whom he held before he knew he was contagious.

Get CNN Health's weekly newsletter

Sign up here to get The Results Are In with Dr. Sanjay Gupta every Tuesday from the CNN Health team.

Public health officials have recently expanded access to the Jynneos monkeypox vaccine to children under certain circumstances.

Griffin says that although the vaccine should be safe, there’s no data on its use in kids. TPOXX is also recommended for children under the age of 8, a group the CDC says is at higher risk for severe outcomes from the virus.

For now, the man is stuck in his basement and unable to help at home, which Griffin said has been tough for him and his family.

“The dad, who is really important in the first few weeks of baby’s life, is now locked in the basement, which is tragic,” Griffin said. “You don’t get those weeks back.”