Twenty years ago, then-New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg was under pressure to build more public bathrooms. He responded with an answer that represents how most of the United States has handled public bathroom access for decades.

“There’s enough Starbucks that’ll let you use the bathroom,” he quipped.

And in fact, private companies like Starbucks (SBUX) did step in for years to offer their public toilets as local and state governments essentially outsourced a public service to private companies.

Starbucks has at times embraced an open-bathroom policy, and shied away from it at others. Now, the coffee chain is effectively saying it can’t be America’s public toilet any longer.

Last month, Starbucks’ interim CEO Howard Schultz said the company might not be able to keep its bathrooms open, blaming a growing mental health problem that poses a threat to its staff and customers. “We have to harden our stores and provide safety for our people,” Schultz said at a conference. “I don’t know if we can keep our bathrooms open.”

Starbucks’ re-evaluation of its restrooms highlights the pressing need for local, state and federal government to prioritize public bathroom access.

“The commercial solution is really not a great solution,” said Lezlie Lowe, a journalist and author of “No Place to Go: How Public Toilets Fail our Private Needs,” published in 2018.

“It’s leaving what is clearly, without doubt, a necessary amenity for the use of our cities in the hands of private companies. No rational person would want Starbucks to pay for traffic lights or street lights.”

No place to go

There aren’t enough places in the United States to go to the bathroom, let alone clean, safe and fully-resourced facilities.

Without adequate public toilets, people go in places that put them at risk of arrest, jeopardizing public health and adversely affecting neighborhoods’ livability. The lack of public bathrooms is a dire problem for people experiencing homelessness, delivery workers who spend hours on the road, and people with health conditions or disabilities. Women also usually have to wait in longer bathroom lines than men.

“It’s an ongoing sanitation crisis, and it highlights American inequality and marginalization,” Catarina de Albuquerque, chief executive officer of the United Nations Sanitation and Water for All global partnership, wrote in an op-ed this month. “Like food, water and shelter, access to safe sanitation is a fundamental human right.”

In 2011, de Albuquerque assessed US water and sanitation services for the United Nations and found that, despite being one of the wealthiest countries in the world, the United States “had woefully inadequate availability of public restrooms” — only eight per 100,000 people on average, the same number as Botswana. Iceland leads the world with 56 toilets per 100,000 people.

Public bathrooms in the 20th century

There is no easy answer to how the United States arrived at this conundrum, but public restrooms have long been a political battleground, from segregated Jim Crow facilities to laws that target transgender people.

The height of the drive to create public bathrooms came during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Before then, public urination was common. In cities, saloons were often the only option.

“Urinating men, like defecating horses, were an everyday sight on the street. ‘Ladies, passing on the sidewalks, are frequently subjected to indelicate displays that they cannot avoid witnessing,’ reported one observer,” wrote historian Peter Baldwin in a 2014 journal article.

A coalition of housing reformers, doctors and public health experts, women’s groups and temperance activists grew concerned about the problems created by a lack of public toilets. The latter’s concerns focused on men who were using saloons’ bathrooms and staying longer to keep drinking.

Before Prohibition went into effect in 1920, cities raced to build public bathrooms to head off the coming shortage created by the closure of bars, according to Baldwin. In subsequent decades, local governments closed public bathrooms and cut hours due to high maintenance costs, budget shortfalls, crime and other factors.

Private businesses then stepped in to fill the void, such as gas stations as more people began to hit the road, fast food chains like McDonald’s (MCD), and eventually companies like Starbucks.

Starbucks’ stance on bathrooms

The coffee chain has for decades been a solution for those desperate for a bathroom.

In 2004, a New York Times reporter wrote a tongue-in-cheek guide for people attending the Republican National Convention in New York City. “Public toiletlessness is the shame of the city,” he acknowledged. He recommended the visitors do as the locals do: go to Starbucks.

That wasn’t necessarily a bad thing for the chain. Starbucks has positioned its thousands of stores as a “third place,” after work and home — a place to grab a coffee on the go, or one where you can sit, sip a latte and bond with friends or strangers.

Opening its restrooms to the public has helped brand Starbucks as a place for members of the community, and is also a great way to bring potential customers through the door.

“Starbucks made money by maintaining bathrooms. They benefited from the absence of government,” said Bryant Simon, a Temple University historian who wrote a book about Starbucks and is currently working on one about public bathrooms.

But allowing free access to its bathrooms often puts a burden on Starbucks employees. In 2011, The New York Times reported on baristas who went rogue by locking store bathrooms because they were “tired of customers — and noncustomers — leaving bathrooms messy or worse.”

The article noted that “in a city with few other options, people reacted as if Starbucks was revoking a public entitlement.” Starbucks then stepped in, instructing workers to leave the bathrooms open, according to the article.

The company codified its bathroom policy in 2018 after two Black men were arrested at a Philadelphia Starbucks while waiting for a friend. One of the men said he asked to use the restroom shortly after walking in and was told it was only for paying customers. Minutes later, a store employee called 911.

Starbucks apologized and set up anti-bias trainings for its workers. It also officially informed employees that bathrooms were for everyone.

“Any person who enters our spaces … regardless of whether they make a purchase, is considered a customer,” Starbucks said in an email to workers at the time. But the commitment has proved challenging.

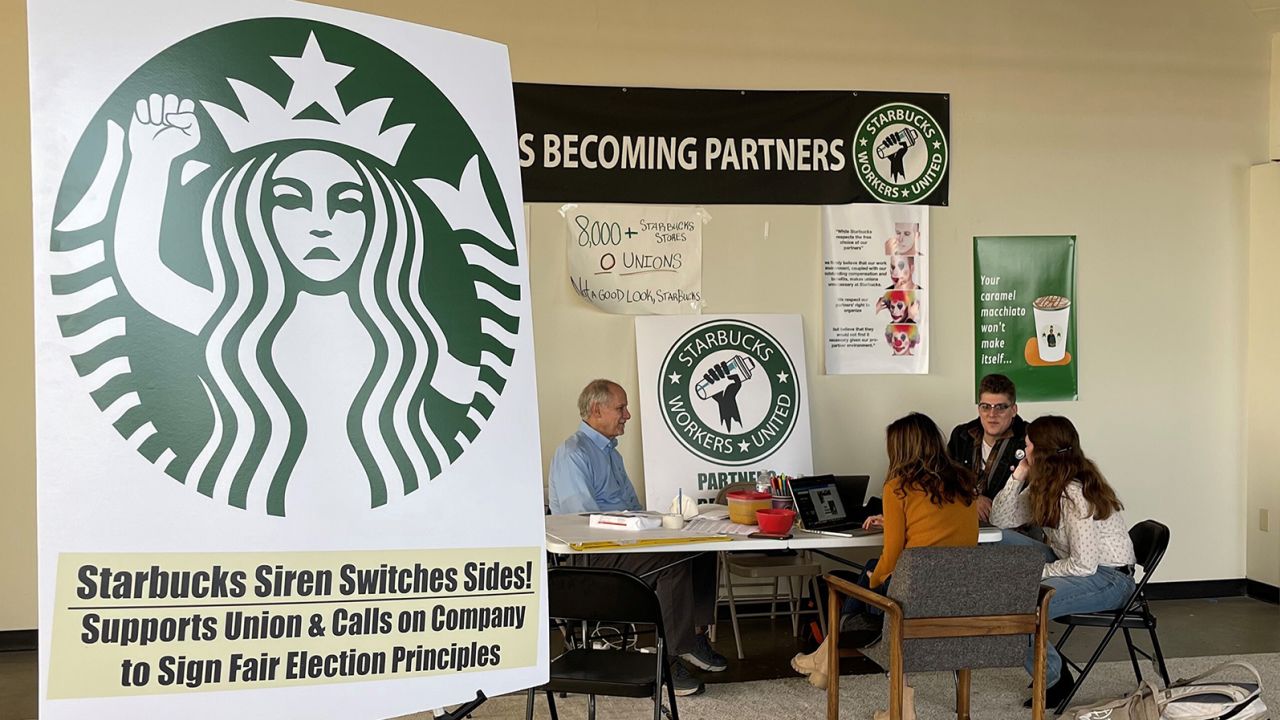

This month, Starbucks said it was closing 16 stores, citing safety concerns. In an open letter outlining the steps Starbucks is taking to try to keep workers safe, members of the US leadership team listed “closing restrooms” as part of the effort. The changes come as Starbucks fights a growing unionization drive.

In a July memo, Schultz talked about the challenges facing Starbucks and the country overall.

“Our stores serve as windows into America,” he said. “We find ourselves in a position where we must modernize and transform the Starbucks experience in our stores and recreate an environment that is relevant, welcoming and safe.”

It can’t be left to companies to solve the quandary of public bathrooms, said Temple’s Simon. “Only an invigorated and robust state can solve it.”