Editor’s Note: Lala Tanmoy (Tom) Das is an MD-PhD student at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City who has been barred from blood donation for being gay. Follow him @TanmoyDasLala. The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of the authors. View more opinion on CNN.

I’ve struck out three times trying to get a monkeypox vaccine appointment in New York City.

I tried and tried again, but between dwindling supplies, huge demand and difficulties with the appointment website, each time I failed.

On Tuesday, New York City Health Commissioner Ashwin Vasan said that 9,200 vaccination appointments were fully booked in just seven minutes after they went online last week. It should come as no surprise, then, that New York City’s health department decided to switch its two-dose vaccination strategy to a one-dose strategy. Vasan said the agency hasn’t scrapped the second shot but is focusing on first shots for now.

The demand outpacing supply is a problem we could have prevented; demand was and is largely predictable as cases in the US are still mostly limited to men who have sex with men (MSM) – many of whom self-identify as gay, bisexual or transgender. And studies consistently show that LGBTQ individuals are much more likely to get vaccinated than our heterosexual peers – including getting the Covid-19 vaccine.

There is no doubt that there is an urgent need to fast-track the delivery and distribution of more vaccines. But, as a gay physician-in-training who has taken care of LGBT people in low-income and immigrant neighborhoods, I am worried that our current approach to rationing available vaccine reserves is not equitable and disadvantages individuals who may need it the most.

First and foremost, we need to prioritize vaccine distribution in Black and brown communities. This includes not just opening up sites in predominantly minority neighborhoods but ensuring that people who live there can access them. Latest surveillance data from the NYC Department of Health shows that non-white individuals make up a larger share of known monkeypox cases than white individuals. Additionally, 2 out of every 5 cases are outside Manhattan and Staten Island, in boroughs that are predominantly non-white. Other cities, like Atlanta, appear to have a similar racial/ethnic disparity among known cases, with Black individuals being impacted more.

Yet, based on what I’ve heard from Black and brown peers and patients, and corroborated by what’s being anecdotally reported on social media, people of color seem to be having a very difficult time securing vaccination appointments. As more doses become available in the future, we need to adjust our distribution strategies so that these individuals and their communities are not further stymied. Releasing anonymized sociodemographic information on who is getting the vaccines and in which neighborhoods may help ensure that minority neighborhoods are being reached.

We also need to supplement the current approach in many cities of first-come-first-served, online-only scheduling portals with pre-registration (like Washington, DC is doing) and walk-in options. As we witnessed with the Covid-19 vaccine rollout, the online, first-come-first-served system disadvantages anyone who has work or other obligations that prevent them from getting online the minute appointments are released, as well as people with unstable housing who don’t often have access to digital technology.

There are also still a fair number of MSM who prioritize anonymity and discretion over health. I’ve seen this not only in my own patient pool but in conversations with people online. Many of these individuals don’t feel comfortable with the digital traceability of online portals. We are doing a disservice to people if we don’t employ different, more discreet strategies such as walk-in appointments with no online registration.

Language equity, too, is important when disseminating information on vaccine updates, especially in urban centers like New York, which are linguistically diverse. I know several gay men who only speak Mandarin or Portuguese and who have struggled to understand the updates released about vaccine availability. Though webpages can often be translated, cities should look into ensuring that monkeypox information and updates about vaccine availability are efficiently and accurately reaching those who are not native English speakers.

Finally, current eligibility criteria encourages people with immunocompromising conditions to seek out vaccines, but they are not afforded priority in a first-come-first-served scheduling portal despite the fact that some early data indicates that those who are immunocompromised – including from uncontrolled or poorly controlled HIV – may have more serious outcomes from monkeypox. We should prioritize vaccinations for these individuals.

Get our free weekly newsletter

- Sign up for CNN Opinion’s newsletter.

- Join us on Twitter and Facebook

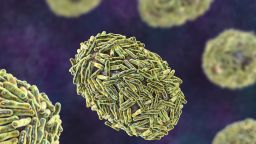

The monkeypox situation is rapidly evolving. In New York City, we went from one case in May to over 600 in mid-July. And even though a majority of known cases have been in adult men, Dr. Mary Bassett, commissioner of the New York State Department of Health, mentioned in a recent town hall that health authorities are starting to see cases in children. Renewed emphasis on vaccination as well as primary prevention will be critical to curbing the spread of the virus in different groups.

There is no perfect, one-size-fits all solution to vaccine distribution challenges that will cater to everyone’s needs. But it is especially important to me, as an immigrant and a physician-in-training, to be able to advocate for the needs of disadvantaged groups that I serve. I must vouch for their visibility in the public health system to help ensure that access to resources is equitable for all New Yorkers.