Editor’s Note: Yanzhong Huang is a senior fellow for global health at the Council on Foreign Relations and a professor at Seton Hall University School of Diplomacy and International Relations, specializing in Asia. He is the author of “Toxic Politics: China’s Environmental Health Crisis and Its Challenge to the Chinese State.” The views expressed here are his own. Read more opinion on CNN.

Those dismayed by China’s zero-Covid policy were likely also shocked that Beijing’s Communist Party chief Cai Qi reportedly said this week the city might keep the policy in place “for the next five years.”

While the phrase did not seem to be in Cai’s original report and government censors quickly removed the misleading quote, the huge backlash the news sparked in social media raises the question of whether China is indeed serious about pursuing zero-Covid as a long-term strategy (let’s call it “long zero-Covid”). And if so, how feasible is it – and what that means for China and the world.

As Chinese government officials have repeatedly said, a dynamic zero-Covid strategy does not seek absolute zero infection. Instead, it focuses on cutting the local transmission chain and bringing the situation under control in the shortest period once a local flareup or outbreak is detected.

With the emergence and global spread of new subvariants that can evade immunity provided by vaccination and prior infections, however, any victory against the virus under zero-Covid is short-lived.

That China continues to face the threat of being overrun by the virus justifies the application of the strategy until the end of the pandemic (which is not in sight anytime soon).

True, the Omicron variant appears to be less severe than the original one – Shanghai registered a 0.1% Covid-19 fatality rate between April 1 and May 31, the same level as the seasonal influenza.

State media and top government epidemiologists nevertheless still highlight the danger of the variant, and the worst-case scenario – featuring mass die-off and collapse of hospital systems – is still defining the official narrative on the potential consequences of pivoting away from zero-Covid.

Witnessing the Covid-19 catastrophe in Hong Kong and the surge of cases in its East Asian neighbors after moving away from zero-Covid, the top brass appears to be convinced that clinging to zero-Covid until the end of pandemic (or at least until truly effective vaccines or therapeutic means become widely available) is the only viable approach to avoid the worst-case scenario.

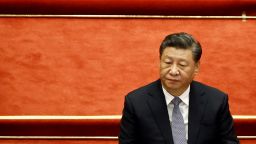

And if China manages to achieve that objective, it can still claim the success of its pandemic response and argue it demonstrates the superiority of its political system. During a visit to Wuhan on Tuesday, President Xi Jinping claimed that China’s Covid-19 response is the most economical and effective in the world and the country “has the ability and strength to implement dynamic zero-Covid until it achieves the final victory.”

How feasible is long zero-Covid? It is hard to dispute that the policy incurs significant socioeconomic cost and is increasingly unpopular among the middle class in China. But in a country where the powerholders are not accountable to the people, popularity has rarely been the main driver of public policy process.

The one-child policy was rolled out even though it brutally infringed the freedom of reproduction that Chinese people had enjoyed for several thousand years. Indeed, initially a proposal pitched to Communist Party and Youth League members in 1980, the idea soon became institutionalized and internalized as a “basic state policy” that lasted for the next 36 years.

In a similar vein, China has moved to routinize pandemic control through regular PCR testing and rigorous health checks in residential communities and public places. The ability to ring fence Covid-19 infections in Shanghai and Beijing bestows confidence among the top decision makers that the Chinese state is still sufficiently resilient and resourceful to keep the virus at bay, no matter how costly and difficult it is.

Other developments also facilitate the pursuit of long zero-Covid. Despite the growing social discontent in large cities like Shanghai and Beijing, public support for the policy appears to remain strong in smaller cities and rural areas (where access to alternative information remains quite limited).

Many Chinese do not oppose zero-Covid, not only because of its promised health benefits but also because of the non-health consequences of infection (for example, being subject to stigmatization as well as strict quarantine and isolation).

Over time, the marginal cost of implementing the strategy may become more tolerable with easier access to testing facilities, steeper drops in the cost of conducting mass testing, the heavy reliance on high-tech means and social forces in monitoring people’s movements and the internalization of zero-Covid rules in the Chinese society.

The sociopolitical, economic and foreign policy impact of long zero-Covid, though, could be much more profound and enduring than the government thinks.

Once people realize that zero-Covid is no longer a transient phenomenon, they will adapt to change by readjusting their expectations and behavioral patterns. As the former editor-in-chief of Global Times admitted once he learned about the possible continuation of zero-Covid in Beijing: “No one wants to live in Beijing for the next five years the same way as how the first half of this year has been.”

Citizens may discount the future more heavily and adopt an attitude of hopelessness. The mental health problem in China, already worsened by the pandemic, would definitely be exacerbated by long zero-Covid. Combined, more people may be emboldened to engage risk-taking behavior, even turning their back on the government.

The government’s refusal to exit from zero-Covid may also accelerate the trend of people exiting from the system and emigrating. Growing uncertainty and risk of doing business in China will also likely prompt investors to reduce their presence in China, leading to the mass exodus of expats.

In the meantime, long zero-Covid will deter foreigners from visiting China even though the government has relaxed entry requirements. In response, China may become more inward looking, even degenerate into another hermit kingdom.

And with intensified misunderstanding and distrust between China and the West, the fall of the Bamboo Curtain will no longer be a distant reality.