What a difference a year makes. Enormous challenges, some of them barely imaginable when the G7 leaders last met 12 months ago, are bearing down on the world’s most prosperous democratic nations as they prepare to meet in Germany.

Optimism was in the air at the Cornish beach resort of Carbis Bay in 2021 as the G7’s presidents, prime ministers and chancellor met face-to-face for the first time since the Covid-19 pandemic began.

Together they vowed to “beat Covid-19 and build back better,” to “reinvigorate economies,” to “protect our planet” and to “strengthen partnerships.”

But global events have since overtaken their best efforts, and it is far from clear if they will be able to build on those goals this year. Russia’s unprompted invasion of Ukraine is a large and singular cloud, but other thunderheads are gathering too.

Over the next few days, the leaders of Japan, Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom, France, Italy, the European Union and host Germany will meet amid the seclusion of Bavaria’s luxurious Schloss Elmau retreat.

The spa resort, nestled in a peaceful valley, usually offers well-heeled visitors a brief chance to escape from the cares of the world – but even Schloss Elmau can’t shield the world’s leaders from the problems gathering on their horizon.

Russian President Vladmir Putin’s officials are hinting at nuclear Armageddon, China has become increasingly assertive, a global food crunch is on the way, oil prices are spiking, and a global economic slowdown and a cost-of-living crisis are looming. Climate change aspirations are also being confounded and supply chain problems are hobbling hopes of a post-pandemic return to normality.

And on top of all that, last year’s summit host, the UK, is threatening to break international laws over its Brexit agreement with the EU – not to mention its controversial plan to deport asylum-seekers to Rwanda – despite the risk of rocking the world order it helped build, and diluting the G7’s already limited effectiveness.

Although G7 leaders can look back with some satisfaction at their unity in the face of Russia’s unprecedented aggression – as seen in that “strengthening partnerships” goal set in Carbis Bay – the scale of looming crises dwarfs even that.

Putin is not entirely to blame for the coming storm but his unjustified war in Ukraine is inextricably linked to many of the crises that are brewing. Without it, the fixes required would be easier and fewer, their impact less pernicious.

Food crisis

The global food crunch is a case in point. It can be blamed, in part, on worldwide post-pandemic supply chain issues, but Russia’s theft of Ukrainian wheat and its blockade of Ukrainian shipping in the Black Sea, which is stopping Ukraine’s wheat and other farm products from reaching international markets, is also playing a major role.

According to the UN’s World Food Program (WFP), Ukraine normally supplies 40% of its wheat; the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) says Ukraine supplies 16% of the world’s corn exports and more than 40% of the world’s sunflower oil.

The global NGO International Rescue Committee (IRC) said recently that “98% of Ukraine’s grain and wheat exports remain under blockade,” adding that “food prices worldwide have rocketed by 41% and a further 47 million people are projected to experience acute hunger this year.”

Traditionally Ukraine’s wheat and grain exports go to some of the world’s neediest nations: Libya, Lebanon, Yemen, Somalia, Kenya, Eritrea and Ethiopia.

To improve the situation, the G7 will need to get Putin to back down on some of his war aims, for example by ending the conflict, or restoring Kyiv’s control over all Donbas – but so far there is no indication he is anywhere near doing that.

Energy crisis threatens climate commitments

Rising oil prices are another by-product of Putin’s war – albeit one complicated by the fact that oil production is not matching up to post-pandemic increases in consumption. To fix this, the G7 will need to convince Russia’s OPEC+ partners, including Saudi Arabia, to turn their back on Putin and increase oil output.

US President Joe Biden’s trip to Jeddah, planned for mid-July, and UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s trip to Riyadh back in March offer hints that the G7 may be making some headway on this, but there are no guarantees yet. Saudi Arabia – like Russia – benefits massively from high oil prices; their gain is pain for the billions stuck with the bill of getting food to market.

Last year’s G7 was all about net zero and a green pandemic recovery, but this year’s scramble by Western nations to wean themselves off Russian oil and gas has given a boost to the biggest single contributor to the crisis – coal.

G7 host Germany is now in crisis mode as Russia reduces its gas supplies to the country, weaponizing energy for influence as feared – it is now saying it will fire up more coal plants. That’s a U-turn from last November, when Germany brought forward its deadline to phase out coal to 2030, eight years earlier than planned. After Russia’s invasion, it also expedited plans to transition its power sector to 100% renewables by five years.

Johnson – who said last year the world had reached a point of no return in phasing out coal – just this week suggested the UK start mining the fossil fuel again for steelmaking. The country will also delay a plan to shut down more existing coal plants ahead of winter.

And to address the oil crisis, Biden is suggesting a tax holiday on fuel as prices at the pump soar.

Economic pressures

In their Carbis Bay goal to “build back better,” the G7 nations never got their heads around the stuttering return to a pre-Covid normality. Canceled flights and travel chaos across Europe and beyond this summer are just the visible tip of an iceberg-sized problem that is defying quick fixes.

China’s insistence on continuing to enforce a “zero Covid” strategy is confounding not only its return to business as usual, but also rippling through global supply chains, with lockdowns keeping workers from factories and in the worst cases halting production. Despite growing tensions with the G7 nations, China shows no signs of aligning with their new post-Covid norms.

In G7 nations and beyond, inflation is rising, central banks are raising lending rates and a global economic slowdown seems far more likely this year than last. The world’s richest man, Elon Musk, predicts that a US recession is “inevitable.”

Problems are layering in a way that is somewhat reminiscent of the global economic downturn in 2008.

Back then, central bankers rallied and stopped the economic rot, but the geopolitical repercussions rippled on for years.

The Arab Spring signaled that economic pain had passed a threshold. When impoverished Tunisian street trader Mohamed Bouazizi set fire to himself in December 2010, he ignited passions across the Middle East; protesters took to the streets, toppling two governments and rattling many more, before calm was partially restored in the region later the following year.

It is not impossible that another global economic crisis could trigger an even wider wave of unrest. In recent months, Sri Lanka has seen economic turmoil spill on to the streets. Rising prices have also sparked popular unrest in Pakistan and Peru.

Putin banks on faltering consensus

What G7 leaders can do to head off a season of despair could well be limited by the global rifts which Russia is intentionally exploiting.

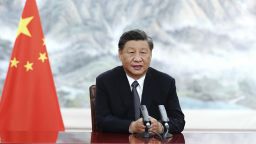

Just weeks before Putin’s forces invaded Ukraine he went to China and met President Xi Jinping; the pair promised deeper cooperation and, despite warnings from G7 nations and others, Xi has doubled down on that commitment and become more assertive over the future of Taiwan.

Consensus at the UN and the G20, two other deep-pocketed global crisis firefighters, is in tatters. Votes at the UN Security Council show veto-wielding Russia and China will prevent any censure of Putin’s invasion; meanwhile, the US has suggested it won’t attend the G20 Leaders’ summit in Indonesia this November if Russia goes, and the UK has done the same.

China has refused to denounce Russia over its invasion of Ukraine and both have become bellicose towards what they see as the vested interests of the world’s leading democracies – the G7 nations – against them.

They know developing world problems impact G7 nations before them – as most migrants choose to go to developed countries that will protect their rights – and seem willing to leverage world crises to their advantage, leaving the G7 to weather the coming storm alone.

But so far, despite differing relations with Russia, the G7 is holding together.

France’s Emmanuel Macron has talked to Putin more than any other G7 leader over the past year, and insists that Russia “should not be humiliated,” while Biden accuses Russia of having “fueled a global energy crisis,” by invading Ukraine and his defense chief Lloyd Austin says Putin should be “weakened.”

What’s clear is that this G7 has more riding on it than past meetings: Success will come in mitigating the crises, not stopping them. Failure is exactly what Putin wants.