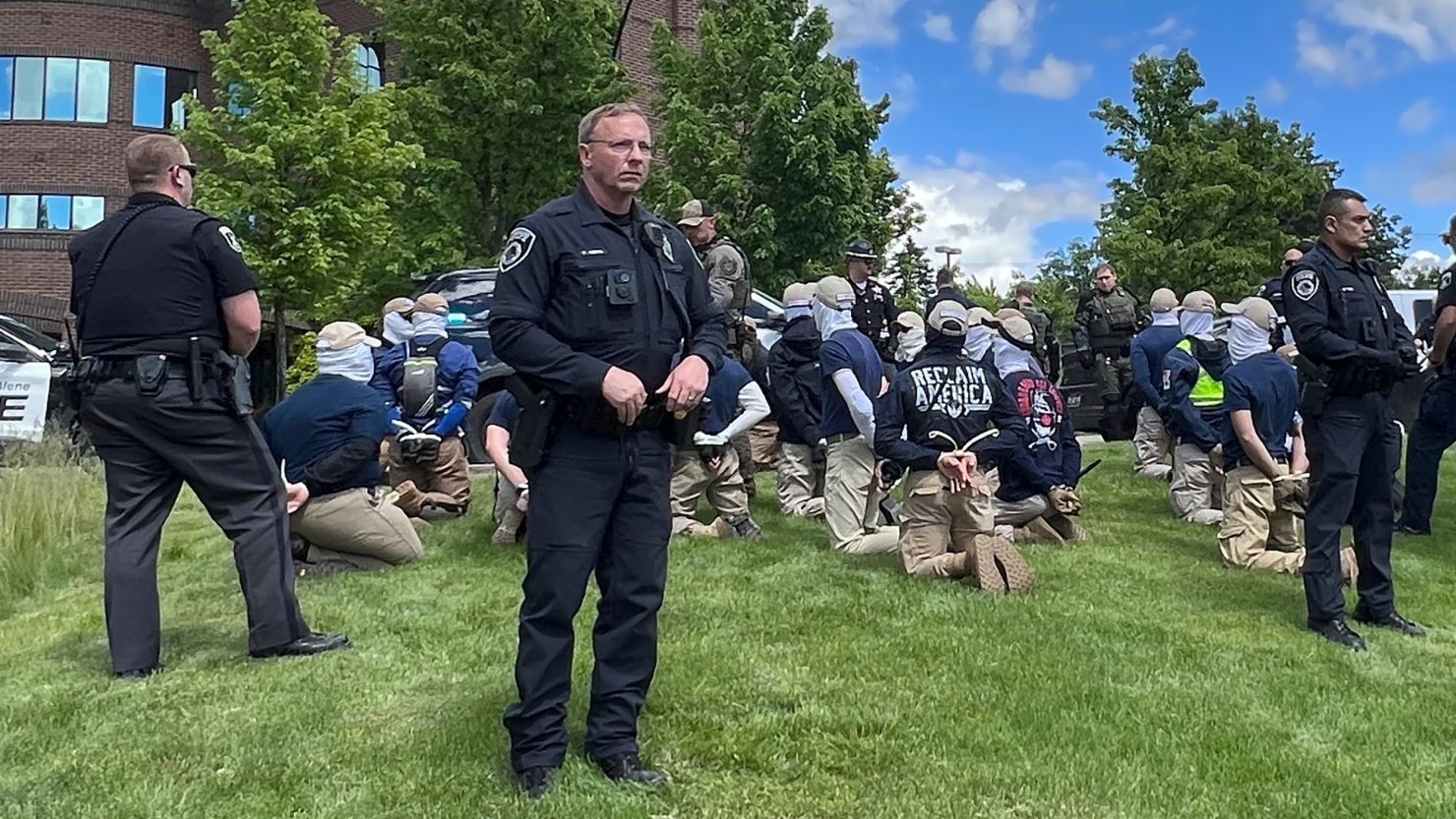

The recent arrests of 31 people accused of planning to riot near a Pride parade in Idaho might be perplexing to some, but White supremacy goes beyond just intolerance for certain racial groups.

White supremacy has long been bound up with rigid views about gender, masculinity and sexuality.

Take a long-since-forgotten Ku Klux Klan raid on a gay nightclub in what’s today Miami-Dade County. In November 1937, nearly 200 members of the Klan, wearing spectral robes, publicly burned a cross during an induction ceremony.

Then they descended on La Paloma nightclub, where they assaulted patrons in an attempt to close a joint that the Klan saw as an affront to tradition.

Julio Capó Jr., an associate professor of history at Florida International University, analyzes how the raid and transnational forces shaped the city’s history in his 2017 book, “Welcome to Fairyland: Queer Miami Before 1940.”

Capó has written before that the Klan claimed that its actions during the raid and elsewhere “represented its commitment to saving White homes, families, women and traditions.”

To further explore the White supremacist dynamics that were on display last weekend in Idaho, we spoke with Capó, whose research focuses on how gender and sexuality have historically intersected with ethnicity, race, class and other aspects of identity.

Our conversation has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Why would White supremacists target a Pride event? Isn’t their bigotry focused elsewhere?

Homophobia is often rooted and embedded in anti-Blackness, in forms of White supremacy, including in building a particular vision of what the nation should look like or what they (White supremacists) imagine the nation should look like. Homophobia, whether it looks like an attack on a gay club or different forms of policy, is very much about White supremacy. Homophobia and White supremacy are often parts of the same structure.

The names of White supremacist groups change over time. But their core ambitions stay the same: They want to maintain a rigid social order. Could you give an example of a historical parallel that might put into context what happened last weekend?

As advances are made in, for example, LGBTQ rights, there’s a kind of fear among White supremacist groups that they’re losing their power. This story is now decades if not centuries old.

When I was writing my book, I uncovered a raid on a gay bar on the outskirts of Miami called La Paloma. It was raided in November 1937, but not by police. It was raided by nearly 200 members of the Ku Klux Klan.

A lot of people wanted Miami to be this town where they could live what they imagined to be a moral life (or) or live in what they wanted to be a model city. The city relied heavily on its tourist industry and on things like queer culture and queer entertainment, which provided forms of tourist dollars and pesos from the Caribbean and Latin America during this time.

There was a debate about what Miami should look like, and the Klan wrote to the city commission basically saying, “Hey, there’s all this stuff going on, and if law enforcement looks the other way, we’ll take this into our own hands,” and they did. They raided the club.

We could even take this more recently to Charlottesville, where some of the chants that you heard were “f**s, go home.” So, this isn’t a new story.

Among some White supremacist groups, there’s talk about declining birth rates and shifting demographics. Are there any links between these ideas and White supremacists’ perceptions of LGBTQ communities?

So much of this is at the root of anti-Blackness and anti-LGBTQ sentiments. Whether it was the integration of Black children into schools that had historically been White or something else, people have always talked about being concerned about children. The modeling and the language of “save the children” often gets employed by a lot of these groups – that no doubt happened in the 1970s with the Anita Bryant campaign. Much of this is tied to child protectionist language and to a very particular idea of what morality looks like or doesn’t look like and the dangers of being exposed to LGBTQ history or people. And the same with Black history. It’s such an interconnected history.

What do you think is important for people to take away from an attempted White supremacist riot near a Pride parade? It seems hard to separate this conspiracy to riot from many Republican leaders’ insistence on demonizing LGBTQ Americans.

We are very much in a particular political climate and in a very difficult time for a number of reasons. We’re seeing these tensions boil over, and not in new ways but perhaps in different ways. Anita Bryant won that battle in the ’70s, but she didn’t win that war.

I think that it’s really important to find moments of hope. With the Idaho Pride event, someone reported it. Someone voiced their concern. In 1937, La Paloma reopened within just a few weeks, even though the Klan tried to shut it down.

When people still host Pride events, when people still stand up for one another – these are forms of resistance and resilience, and should be understood as such.

The FBI is investigating what happened in Idaho, and a number of cities with upcoming Pride celebrations are giving their security measures a second look. They’re working to prevent violence in the short term. But what do you think needs to be done to find a long-term solution?

One of the things that has to happen is that we really have to understand these issues – anti-Blackness, homophobia, misogyny, classism – as interconnected and in this way combat them. There’s no one quick solution. Rather, there’s a structural one that we need to work toward.