Mckayla Wilkes remembers repeatedly complaining of shortness of breath to her doctors during her entire pregnancy seven years ago.

But she says no one listened. Her concerns were consistently dismissed or minimized while she was pregnant with her daughter, Madison, who is now 6.

After being initially told it was asthma, Wilkes held out for a second opinion, refusing to go home. She was then diagnosed with deep-vein thrombosis and remained hospitalized for two more weeks.

The 31-year-old mother of two says her pain wasn’t taken seriously. “It just really felt like my life as a Black woman and as a Black mother did not matter to everyone,” Wilkes said.

Despite setbacks, Wilkes was able to carry her child to term. But her experience while pregnant highlights a glaring inequality in how Black women are treated in health care settings. And it’s an injustice that will likely be exacerbated by the recent spate of state abortion laws, maternal health care advocates fear.

Near-total abortion bans have been introduced in 30 states this year, according to the Guttmacher Institute, a research group that supports abortion rights. This past week Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt signed a near-total ban on abortion into law, making it illegal to perform an abortion except for medical emergencies. Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis also signed an anti-abortion measure into law, which bans abortions after 15 weeks of pregnancy.

Oklahoma and Florida’s bills are just the latest examples of the steady rise in restrictive measures across the US limiting women’s access to abortions, especially for Black women, who are five times more likely to have an abortion than White women.

Maternal health crisis

Experts say there are a variety of factors making Black women likelier to seek an abortion, including unequal access to housing, education, jobs and health care.

Health care advocates say they fear the attack on abortion rights will create additional risks for Black mothers in what was already nothing short of a maternal health crisis.

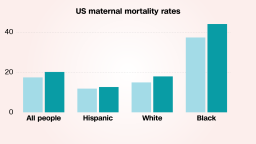

Black women who are pregnant or who have just given birth in the US are three to four times likelier to die than their White counterparts, according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The Century Foundation found for every 100,000 live births, about 19 White mothers die, while about 55 Black mothers die – revealing a stark disparity in the United States.

The disparity is rooted in the lack of access to quality health care for many Black women and implicit bias in medical treatment as well as a range of maternal health complications, according to Anna Bernstein, a fellow at The Century Foundation.

Last year, advocates warned that abortion bans would disproportionately impact Black women who would be forced to carry their pregnancies to term despite potential health risks and will be left with few options for abortion care if they don’t have the means to travel out of state for the procedure or raise a child.

The concern had been raised by lawmakers such as Rep. Cori Bush, who shared her personal experience getting an abortion after she was raped and became pregnant as a teenager.

Bush recalled feeling she’d be unable to raise a child at 18 and said she experienced discrimination when she sought health care for her pregnancy.

“To all the Black women and girls who have had abortions or will have abortions, we have nothing to be ashamed of. We live in a society that has failed to legislate love and justice for us. So we deserve better. We demand better. We are worthy of better,” the Missouri congresswoman said. “So that’s why I’m here to tell my story.”

So what will happen if fewer abortions can be performed?

A study published last year in the journal Demography focused on the effect of a total abortion ban on pregnancy-related mortality. The study found banning abortion nationwide would lead to a 21% increase in the number of pregnancy-related deaths for all women and a 33% increase among Black women.

The study also found that denying all wanted induced abortions would increase the lifetime risk of dying of pregnancy-related causes from 1 in 1,300 to 1 in 1,000 among Black women.

The author of the report, Amanda Stevenson, a sociologist at the University of Colorado at Boulder, told CNN she cried when she finished the study, concluding more Black women would die as a result of a total abortion ban.

Abortion bans are ‘compounding tragedy’

“To be killed at such a hopeful moment in someone’s life is just such a tragedy and to be killed because of a pregnancy that you would terminate if you could is just compounding tragedy,” Stevenson said.

Stevenson believes structural racism is one of the leading causes of racial inequities in maternal mortality and morbidity rates in the United States. And experts say Black women are likelier to seek an abortion due to the broader inequality in society at large – a vicious cycle.

“The way that people end up wanting to terminate a pregnancy is shaped by structural inequalities in access, (in) the ability to plan your reproductive life,” Stevenson told CNN. “But that’s shaped by one’s experience with racism.”

She added whether one has to be worried about recipient doctors being racist or other issues, it’s “not something that White people have to worry about.”

‘Listen to Black women’

The Black Mamas Matter Alliance, a nonprofit organization, is trying to shift the culture surrounding Black maternal health and justice. Since 2016, the Black-women-led network has been engaged in research and community outreach, said Angela Aina, the executive director. As part of their efforts, they created Black Maternal Health Week, which takes place April 11-17 and was recognized by the White House in April of last year.

This week, Rep. Alma Adams, Rep. Lauren Underwood and Sen. Cory Booker introduced companion resolutions in Congress recognizing Black Maternal Health Week. In a joint statement, the lawmakers said the goal is “to bring national attention to the maternal health crisis in the United States and the urgent importance of reducing maternal mortality and morbidity among Black women and birthing persons.”

During a roundtable on the challenges and opportunities to improve Black maternal health, actress Jazmyn Simon shared her story of experiencing bias when she was fresh out of college and pregnant.

She recalls that a White doctor assumed she was promiscuous, and she overheard him saying that he had swabbed her for STDs. Simon says she was confused because she had only one boyfriend.

“His biases against me made him see me in a different light because I was young, poor and Black. … We need to teach doctors to treat everybody equally.”

Aina, of the Black Mamas Matter Alliance, often hears stories from Black women about how their concerns are minimized when they seek care or present symptoms of distress and pain while pregnant. She said Black mothers are often ignored or not given access to a physician when needing care. She is worried matters will only get worse as abortion restrictions rise in the United States.

“We know how deadly it can be when you don’t listen to Black women when they’re saying that they’re in pain and that they need care,” she said.

She said Black women, and Black women who are pregnant in particular, “are still devalued.”

Aina said continuous abortion restrictions will drive up Black maternal mortality and can also lead to negative infant health outcomes. She said the Black Mamas Matter Alliance is pushing for a nationwide movement around comprehensive policies on the state and federal levels to protect maternal health care.

“There’s a real negative narrative around Black women, Black girls and Black motherhood that really drives a lot of the ways in which Black birthing people in general are treated in the health care system,” Aina said. “We want change, and we want to see an end to maternal mortality.”

The most recent abortion bans or restrictions fit into a history of limiting reproductive freedom.

Breana Lipscomb, the senior adviser for maternal health and rights at the Center for Reproductive Rights, told CNN the various abortion restrictions across the US are part of a larger and targeted effort that has been going on for decades since the Roe v. Wade Supreme Court case in 1973.

“Black women have long been subjected to reproductive coercion in this country,” Lipscomb said. “The way forward is not to double down on government coercion in personal health decisions, but instead to make sure that everyone has reproductive freedom.”