The steel mill that looms over low-slung neighborhoods in Pueblo, Colorado, is a rare bright spot for American manufacturing. Once part of the state’s largest private employer, pumping out steel that was used to build rail lines across the Western US, it is now in the midst of a major expansion and recently became the world’s first steel plant to run almost entirely on solar power.

But in the wake of the invasion of Ukraine, the steelworkers and their city are grappling with an unpleasant reality that is no longer easy to ignore: The mill is owned by a company that has been accused of potentially supplying steel to build Russian tanks and whose largest stakeholder is a close ally of Russian President Vladimir Putin.

The plant, which still ranks among the largest employers in the small city of Pueblo, was bought in 2007 by Evraz, one of Russia’s major steel-producing companies. Evraz’s biggest shareholder is the oligarch Roman Abramovich, who was sanctioned by the United Kingdom, the European Union and Canada last month.

In announcing its sanctions, the UK government alleged that Abramovich controlled Evraz and that the company was “potentially supplying steel to the Russian military which may have been used in the production of tanks.” Abramovich was involved in “destabilising Ukraine” through Evraz, the sanctions office wrote.

Evraz, which owns several other steel plants in Oregon and Canada in addition to the Pueblo mill, has denied that it supplies the Russian military and tried to distance itself from Abramovich. But its stock fell by 90% from the beginning of the year before it was suspended from the London Stock Exchange in the wake of the invasion, and its entire board of directors quit. The company nearly defaulted on its debt last month due to a sanctions-related delay in a bond payment.

Evraz’s North American subsidiary and its employees say the steel produced in the US is not going to Russia. The North American operation doesn’t send money to the parent company, and its profits are reinvested in its US and Canadian operations, according to executives.

But in recent years, the parent company’s operations have resulted in billions of dollars in dividends that have largely gone to Abramovich and a handful of other Russian oligarchs. Advocates for Ukraine say they’re distressed that the US hasn’t followed its allies in sanctioning Abramovich, and that a figure with close ties to Putin still holds the largest stake in the company that owns the Pueblo mill.

“There is no clean money among the oligarchs,” said Marina Dubrova, the founder of Ukrainians of Colorado, a non-profit organization that has raised funds to send medical supplies to Ukraine. Even if he were to own a “half percent, even one-tenth of a percent” in the company, she argued, “Abramovich has to be sanctioned and his portion has to go to the highest bidder.”

So far, executives and local employees at the Pueblo plant say there has been no impact on their day-to-day job. But some workers are worried about whether that could change if more sanctions go into effect.

“Just the uncertainty is scary, it’s real scary,” said Rique Lucero, a metallurgical technician who has worked at the plant for 14 years. “We wonder how the war is going to further affect us.”

The Evraz situation is an example of how Russian investment in the West could be complicating sanctions: The company employs more than 1,600 people in the US, and the need to avoid job losses could make officials more cautious about sanctioning Abramovich, sanctions experts said.

And the company also shows that the Russian elite’s money in the US goes deeper than stereotypical luxury items – even reaching a historic icon of American industry.

Most people think Russian “oligarchs have been putting their money primarily into these mega-mansions, these superyachts, high-end artwork, Ferraris, Maseratis,” said Casey Michel, the author of a book on foreign investment in the US. But in addition to those flashy status symbols, he said, “there are so many other significant industries that are wide-open for all this oligarchic money.”

A plant that ‘built the American West’

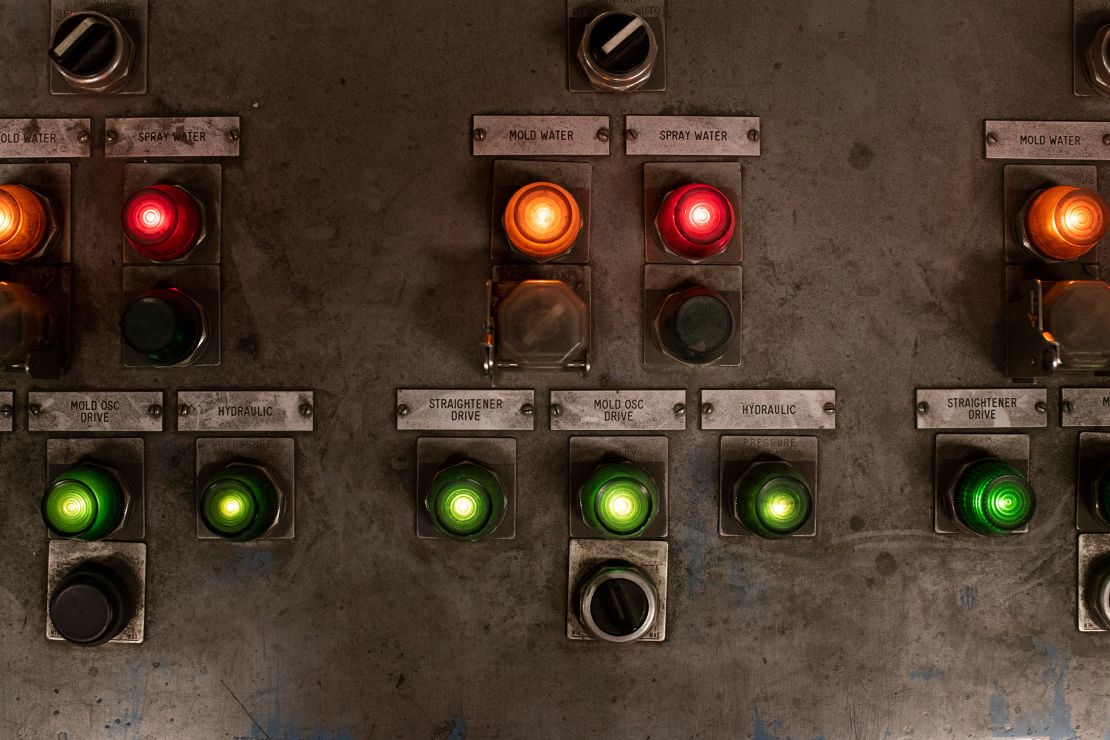

Every hour, tons of recycled scrap metal are dropped into the Pueblo mill’s massive furnace, with a deafening boom and an eruption of golden sparks. The metal is heated at about 3000 degrees Fahrenheit into white-hot, molten steel, then cooled and carefully rolled into rail, wire rod, rebar or pipe.

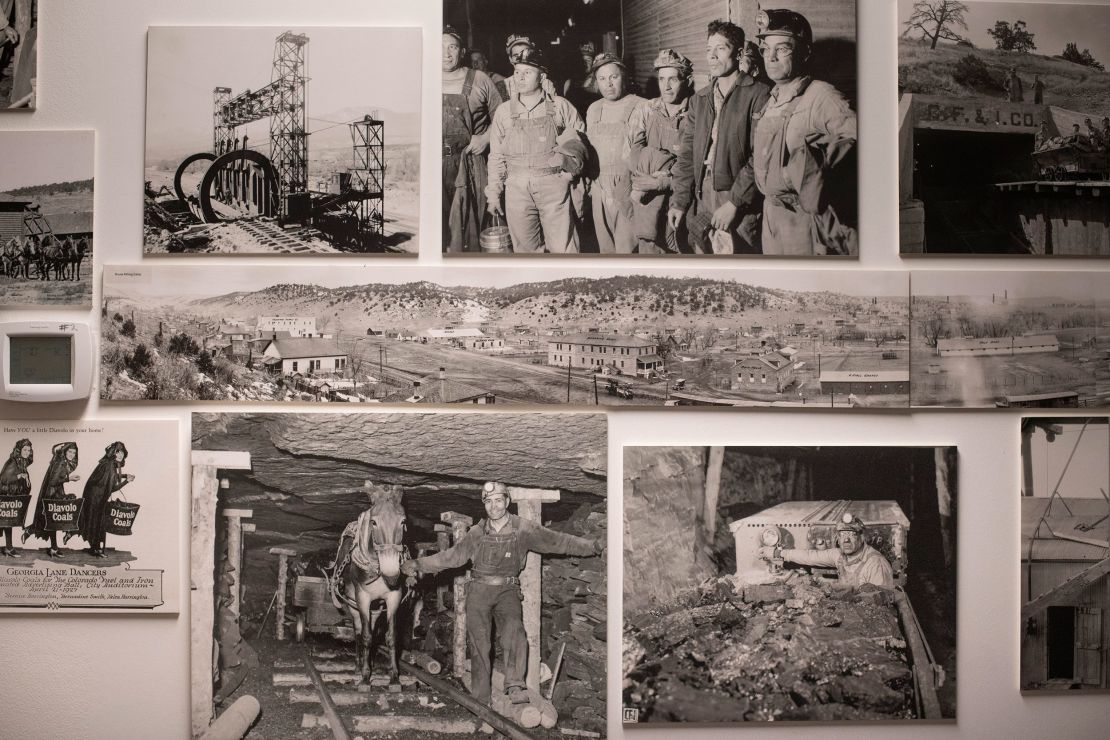

That transformation has been taking place here, in one form or another, since the mill was founded in 1881 as the first steel plant west of the Mississippi River.

Owned by the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company, which grew into Colorado’s largest private employer, the mill attracted workers from around the world. At one point, 40 languages were spoken at the mill and its mines. It pumped out rail that stretched around the region, speeding migration across the sparsely settled Western US.

“This steel really built the American West,” said Nick Gradisar, Pueblo’s mayor, whose father and grandfather worked at the mill, and who worked there himself several summers during college. “It used to be that the fortunes of Pueblo rose and fell on the economics of the steel industry.”

The city experienced the downside of that relationship when the price of steel crashed in the 1980s. Thousands of workers at the plant lost their jobs over several years, local leaders say.

After the downturn, the mill went through bankruptcy and was bought by an Oregon-based company. Evraz bought the parent company in 2007 for $2.3 billion, in what was at the time the largest ever Russian investment in the US.

According to the company’s 2021 annual report, five percent of Evraz employees are in North America and about 16% of its revenue comes from its North American steel operation. Most of its other mills are in Russia and Kazakhstan.

As of February, Abramovich, a globe-trotting owner of the Chelsea soccer team who holds citizenship in at least two other countries, owned the largest stake in Evraz, at roughly 29%, according to the company. But the UK sanctions office argued that he effectively controls the company, which is publicly traded, along with his associates: Four other Russian oligarchs control another 38% of the company.

Evraz has been a lucrative investment for Abramovich and other oligarchs. In 2021, according to its annual report, almost half of Evraz’s profit went to paying out more than $1.5 billion in dividends to its shareholders – two-thirds of which went to the five largest Russian shareholders. Evraz’s financial performance in 2021 “made it possible to pay” such generous dividends, the company wrote in the annual report, citing numbers that included a big increase in earnings in its North American operations.

Abramovich also has myriad investments in the US hidden through complicated networks of shell corporations and hedge funds, The New York Times reported last month. But his shares in Evraz are in his own name, as are two mansions he owns in Colorado ski towns. A spokesperson for Abramovich declined to comment about Evraz.

While the Pueblo mill now has far fewer employees than at its peak, it still puts out about half of all rail used in North America. And while it’s no longer the biggest employer in the city, it’s still the source of some of the best-paying blue-collar jobs in the region, local leaders say.

“Just about everyone that’s a resident of Pueblo has had family that’s worked out there,” some going back four generations or more, said Jeff Shaw, president of the Pueblo Economic Development Corporation.

How Russia’s war could affect Colorado steel

Most people in Pueblo don’t really think of the mill as Russian-owned, according to interviews with city leaders and local residents. Instead of referring to it as Evraz, locals still call it CF&I – Colorado Fuel and Iron – or just “The Mill.”

But the new ownership became impossible to ignore over the last few weeks, when Russia launched its invasion of Ukraine.

Chuck Perko, the president of one of the two United Steelworkers unions that represent workers at the plant, said he got “dozens of phone calls” about the potential impact in the days after the invasion and after the UK and EU governments announced sanctions against Abramovich.

“Retirees are worried, will the company continue to exist, will their pensions stay solvent?” he said. “Families want to know, is my husband or wife going to have a job tomorrow?”

In the weeks since, however, Perko said he hasn’t seen any real impact on the Pueblo mill’s operations. “I’m worried more about the people in Ukraine than I am about my people being affected by it,” Perko added.

Evraz says it’s business as usual in Pueblo. David Ferryman, the Evraz North America senior vice president who runs the Pueblo plant, said watching the war in Ukraine was “heartbreaking,” but argued that critics of Evraz were painting any connection to Russia with “a broad brush.”

“We have our own CEO, we have our own board of directors … we’re about as American a company as it gets,” said Ferryman, sitting in a room in the company’s Pueblo office with walls covered in historic photos of the plant. “Those earnings stay here in North America, and they’re invested into these facilities.”

The US government has not publicly explained why it hasn’t targeted Abramovich with sanctions like the UK, EU and Canada. But Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky asked President Biden in early March not to sanction Abramovich, who has acted as an unofficial go-between for Moscow and Kyiv, in order to allow him to play a role in the peace process, according to two sources with direct knowledge. The Wall Street Journal first reported Zelensky’s request.

It’s unclear how active or central Abramovich has been in the negotiations since then. A Kremlin spokesperson confirmed that Abramovich was involved in peace talks, and he was present at a meeting between the two sides in Istanbul last week.

Treasury Department officials were examining sanctions on Abramovich that would exempt Evraz’s US plants as part of a wide-ranging effort to limit economic fallout of new sanctions, the sources said. A Treasury spokesperson declined to comment about the potential of US sanctions on Abramovich, saying the department doesn’t preview sanctions.

According to sanctions experts, if the US does sanction Abramovich, the Treasury Department would likely issue a license allowing the Pueblo and Portland steel mills to continue operating in order to avoid any impact on American employees.

“If 1,000 Americans are going to lose their jobs, that could impact their decisions,” said Charlie Steele, a former Treasury Department and Department of Justice official who worked on sanctions policy.

Even without US sanctions, the UK, EU and Canadian actions appear to have complicated Evraz’s financial picture, between its stock being suspended from the London exchange and the near-miss in its bond payment. And the broader impact of sanctions can be unpredictable, especially if financial institutions decide they want to avoid the potential stigma of working with companies linked to Russia, experts said.

Even if banks are allowed to work with the company, Steele said, “they might say, I’m not going to get within 100 miles of that.”

Russian investment in America’s industrial heartland

While many major US businesses have expanded in Russia over the last two decades – and are now cutting ties – Evraz is a rare example of investment flowing in the opposite direction.

There are a handful of other US steel plants in the country with ties to Russian oligarchs. NLMK, one of Russia’s largest steel companies, owns plants in Pennsylvania and Indiana. And Severstal, another major Russian steel producer, bought several plants around the US, including in Mississippi and Michigan, before selling them in 2014 as tensions escalated over the invasion of Crimea.

Meanwhile, other proposals for Russian investment in US manufacturing have fallen through over the last decade, in some cases because of past sanctions – including plans for factories in Louisiana and North Carolina.

Most notably, in 2019, Russian aluminum company Rusal announced with great fanfare a $200 million investment to build an aluminum factory in eastern Kentucky, promising hundreds of new jobs in the economically struggling region. The investment came just months after the Trump administration lifted sanctions on Rusal – which had previously been run by oligarch and Putin ally Oleg Deripaska – amid an extensive lobbying campaign by the company.

But the Kentucky factory plan fell apart in recent years as Rusal backed out, leaving an empty greenfield and angry state legislators trying to claw back a $15 million taxpayer investment in the project.

By all accounts, Evraz has done the opposite. Workers say that their new owners have been far easier to work with than the previous, Oregon-based management, whose contentious relations with unions led to years of strikes and labor disputes. And they’re thrilled with the new investments Evraz is making in Pueblo, which have led to a bevy of construction cranes stretching up into the sky around the plant.

“Locally, Evraz has been a great partner,” said Jerry Pacheco, the executive director of the Pueblo Urban Renewal Authority, which has helped fund the expansion.

The company is in the middle of building a new $700 million steel mill that will produce much longer segments of rail, helping them compete for contracts to build high-speed rail lines and other rail projects. The project is set to receive at least $84 million in public incentives from the city and state governments and the urban renewal authority, and potentially up to $118 million — with certain requirements including retaining jobs and paying higher property taxes in the future.

Evraz has invested more money into the Pueblo expansion in recent years than any capital project at its facilities around the world, according to the company’s annual reports.

Evraz also just finished a solar power project that makes it the first steel plant in the world to be powered almost exclusively with solar power – putting it on the cutting edge of green manufacturing. A sprawling field of solar panels now lies just beyond the historic mill buildings, swiveling to face the sun and stockpile the energy needed for the mill.

The public incentives were crucial in keeping Evraz in Pueblo: The company had been exploring the possibility of moving its operation to another state before city leaders agreed to kick in the funding, and Gradisar argued that the taxpayer money was well worth it. “Good jobs for blue-collar workers, those are hard to come by in this day and age,” he said.

Moral dilemmas at an ‘All-American’ mill

Like many communities across the US, Pueblo is stepping up to help Ukraine. The county sheriff donated unused body armor to the Ukrainian military. A boy scout troop held a fundraiser for Ukrainian scouts at the local Pizza Ranch. A new mural painted on the levee of the Arkansas River, which runs through the city, displays the colors of the Ukrainian flag and a sunflower, the country’s national flower.

But there’s little public consternation or debate about Pueblo’s close ties with a company accused of potentially supplying Russia’s war effort.

“It’s not a big concern for me right now,” Gradisar, the mayor, said of the Russian connection to the mill. He said he wanted to see stability at the plant: “Those are tough operations to operate and run, and you need to know what you’re doing.”

“I’ve had people suggest to me we should seize the mill, whatever that means,” Gradisar added. “I didn’t even respond to that.”

Other Pueblans agree that they’re not bothered by the Russian ownership. As she waited for a lunch table at Estela’s Mill Stop Cafe, a popular Mexican joint around the corner from the Evraz offices, Carol Trujillo said she never thought of the company as Russian-owned before the latest string of headlines.

“To us, it’s All-American,” she said of the mill, listing her relatives who had worked there over the years: uncles, aunts, a brother, her grandmother. “I don’t think the ownership matters to what the people do here.”

Some officials in Canada have called on Evraz to divest from its steel mills there, to avoid any connection with the invasion of Ukraine. “That is actually the way out of this in terms of the balance between needing to support Ukraine and accepting those sanctions and protecting the employment and the … livelihood of those workers,” Sandra Masters, the mayor of Regina, Saskatchewan, which is home to a major Evraz plant, said last month.

Perko, the union president, and several other steelworkers said they would be happy to see Abramovich’s shares sold off, or the mill return to American ownership.

“We’re fairly independent to the point that if something were to really happen, we could be ripped away from the parent company and run independently,” Perko said.

Some steelworkers said they’ve been feeling the moral dilemma of working for a company with ties to Russia. Daniel Duran, an accounting clerk who has been at the mill for five years after a string of nonunion, low-paying jobs in construction and at Walmart, said he loves working at Evraz, and credits the job for letting him give his four children a good life in Pueblo.

“Honestly, this job has afforded me everything I have today,” Duran said. “I have always thought of this place as being American hands forging US steel.”

But when he’s turned on the news to see Ukrainian families fleeing Russian tanks, he said he’s found himself getting emotional. “I have my own kids, so it makes it tough to sit there and see all this stuff going on and try turning a blind eye,” he said.

Sitting in his empty union hall, a 100-year-old Mission Revival-style building with long cracks running up the walls, Perko said that watching the videos from Ukraine reminded him of his own family history: his grandmother fled the Soviet army as a refugee from Yugoslavia during World War II.

“I disdain what’s going on over there,” Perko said of Ukraine. “But my company is not Abramovich’s company in my eyes – and so it helps me sleep at night to know that we’ve got so much separation from the larger picture.”

CNN’s Drew Griffin, Scott Bronstein and Phil Mattingly contributed to this report.