President Joe Biden delivered a strong message to corporate executives this week in his 2023 spending plan: Share the wealth.

His administrationwants to discourage stock buybacks, which critics say allow ultra-wealthy executives to manipulate markets while funneling corporate profits into their own pockets instead of the economy.

Last year, companies in the S&P 500 repurchased a record $882 billion of their own shares. That number is on track to reach $1 trillion in 2022, according to new data from Goldman Sachs.

The White House has proposed new rules intended to curb stock buybacks as part of its $5.8 trillion budget plan released Monday. The planwould require company executives to hold on to shares of corporate stock foracertain number ofyears and prohibit them from selling shares for a certain amount of time after a planned buyback. The White House did not specify the exact number of years.

Executives sell more stock in the eight days following a buyback announcement from their companies than at any other time, according to SEC data, repurchases that have made up an increasingly large chunk of corporate profits over the past decade. Corporate stock is owned largely by wealthy Americans: the top 10% wealthiest US households by wealth own about 90% of corporate equity.

Discouraging stock buybacks “would align executives’ interests with the long-term interests of shareholders, workers and the economy,” said the proposal, which echoes a long argued Democratic position that buybacks manipulate stock prices and divert money from companies’growth and innovation.

Other critics of the proposed new rule claim that ending buybacks could hurt companies’ market liquidity and price. Executives typically use buybacks to reduce the number of shares available for purchase, thus increasing demand for their stock and earnings per share.

“Corporate buybacks are a growing part of market structure and a growing part of overall liquidity in the market,” said George Catrambone, head of Americas trading at asset management company DWS. “A company might need to do a buyback to prevent others from gaining control, or because a CEO thinks they’re undervalued,” he added.

Biden’s proposal is still just that: a plan. It must be passed by both the House and Senate to become binding, an unlikely scenario. Buybacks have been a hot button political issue since they were legalized in 1982, when the Securities and Exchange Commission passed a rule allowing companies to purchase their own shares without being charged with stock manipulation.

But even if this no-buybacks plan were to pass, says William Lazonick, president of The Academic Industry Research Network, it wouldn’t address the root problem with buybacks.

“The pressure on the executives to do buybacks is coming from hedge fund activists,” said Lazonick, a longtime critic of buybacks and a professor of economics at the University of Massachusetts Lowell. “The problem is Carl Icahn, Daniel Loeb, Paul Singer, and Warren Buffett. These people have nothing to do with these companies. They hold shares and make a ton of money by exerting pressure on these companies.”

In early March, Amazon (AMZN) announced that its board had authorized the company to buy back up to $10 billion worth of shares, a move greatly encouraged by Daniel Loeb, whose company Third Point held an Amazon (AMZN) stake valued at $784 million at the end of 2021.

In 2014, when Carl Icahn held about $5.3 billion in Apple (AAPL) stock, or a 0.9% share of the company, he regularly demanded buybacks.

“These investors have CEOs quaking in their boots,” said Lazonick.

Corporations could have a difficult time defending buybacks to their investors as an appropriate use of extra cash while the rate of inflation sets 40-year records and the price of essential goods like gasoline and groceries continue totick up.

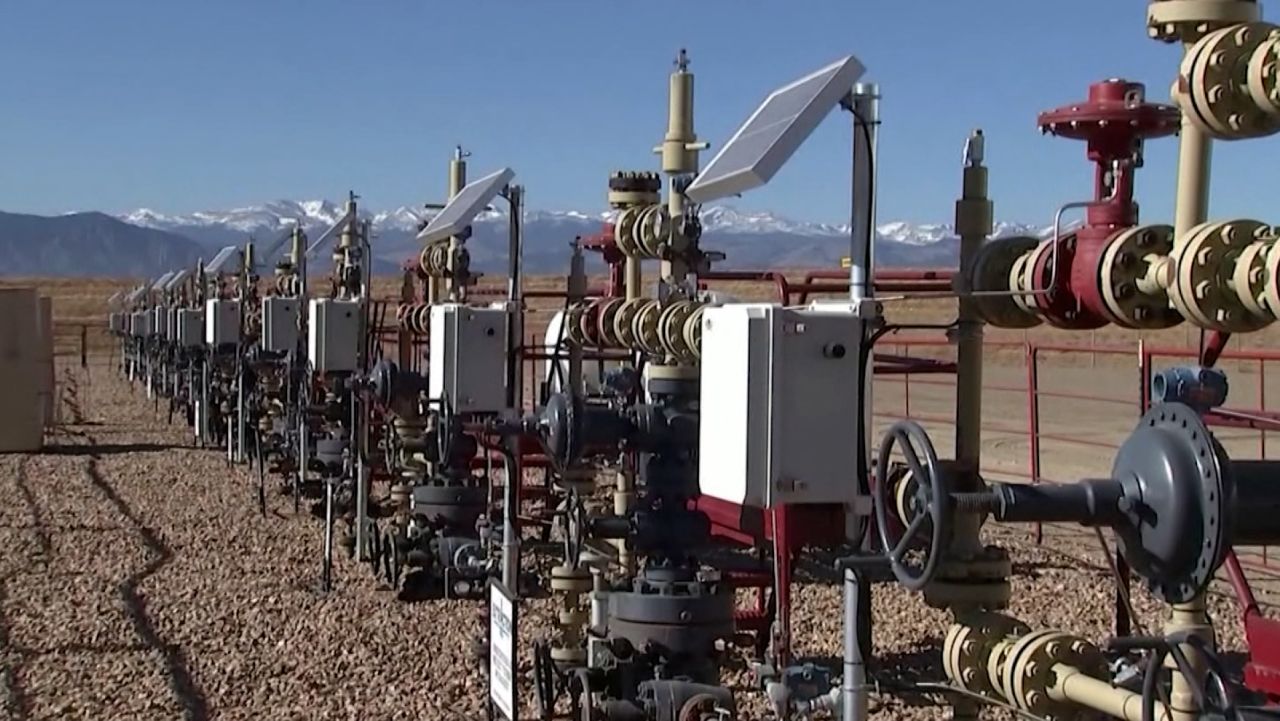

The loss of Russian crude from the market has greatlyincreased oil and gas prices. But rather thanusing those profits to increase production, Exxon recently announced a $10 billion share buyback one day before it announced its best earnings in seven years.

“Oil and gas companies do not want to drill more,” Pavel Molchanov, an analyst at Raymond James, told CNN. “They are under pressure from the financial community to pay more dividends, to do more share buybacks instead of the proverbial ‘drill baby drill,’ which is the way they would have done things 10 years ago. Corporate strategy has fundamentally changed.”