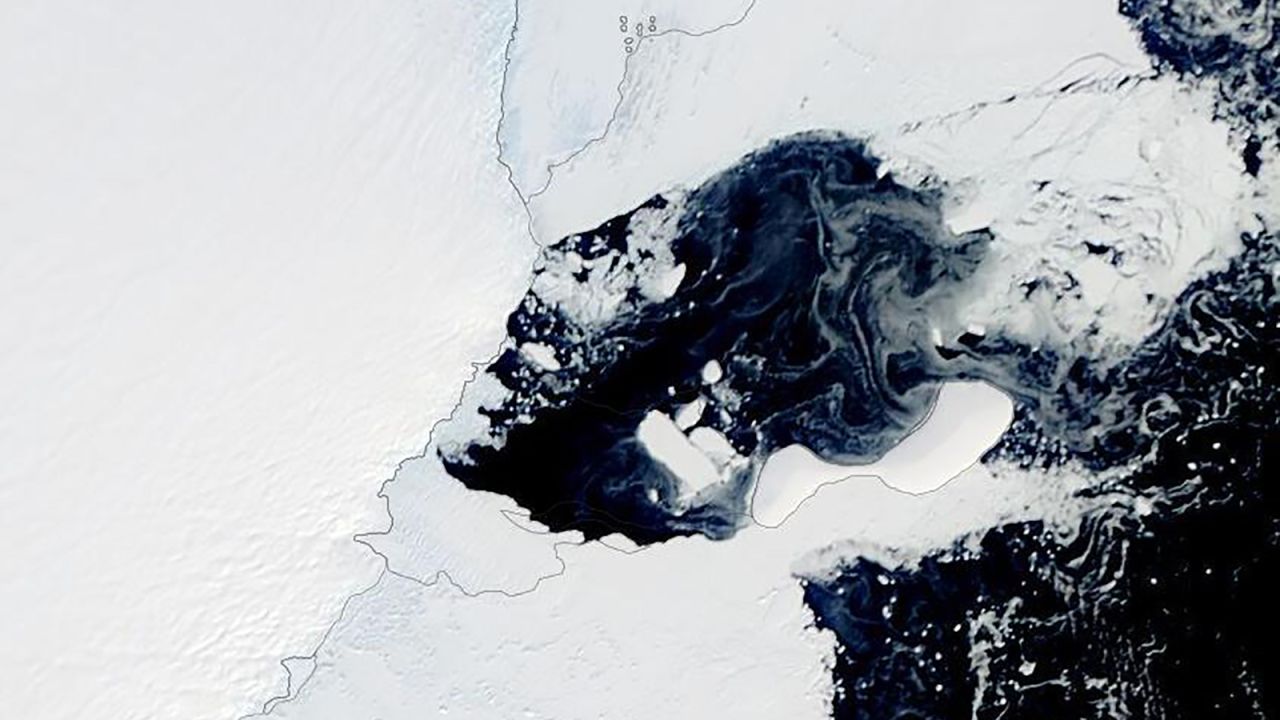

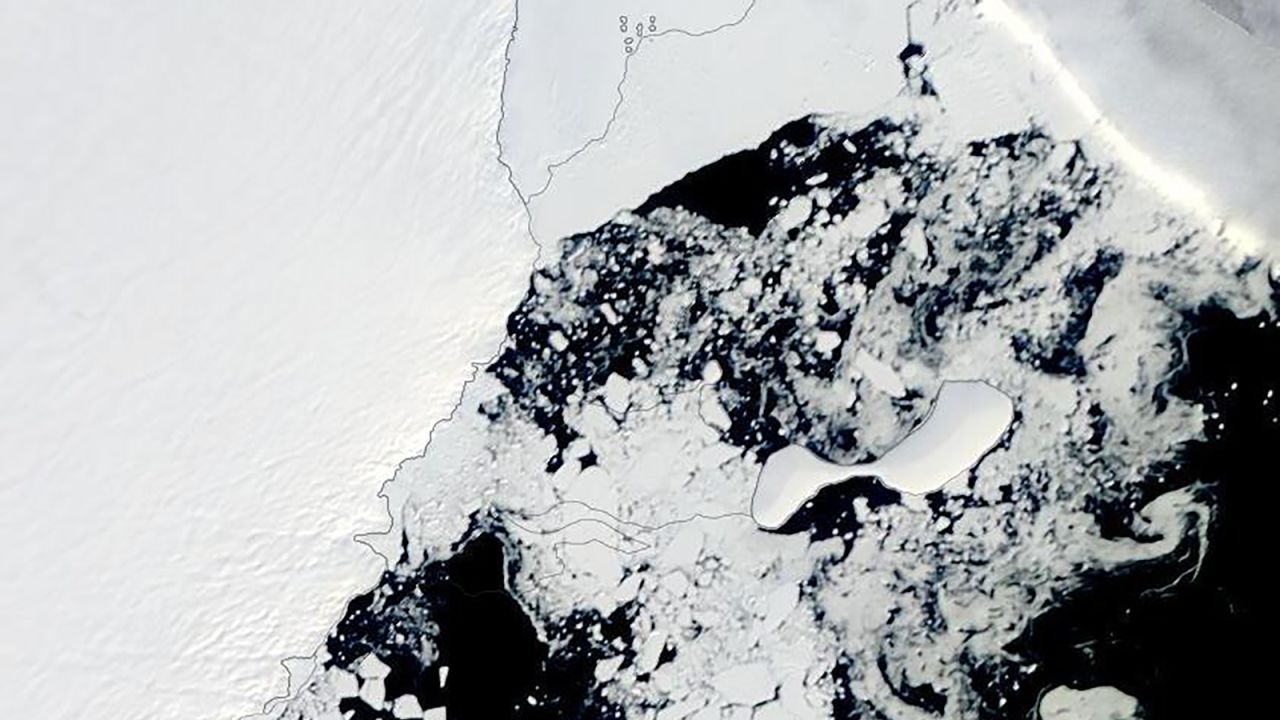

An ice shelf in Antarctica nearly the size of Los Angeles disintegrated in mid-March within days of extraordinary warmth on the continent, scientists say.

The Conger Ice Shelf, spanning approximately 460 square miles, collapsed around March 15. It was around the time temperatures soared to minus-12 degrees Celsius, more than 40 degrees warmer than normal, at the Concordia research station.

“I don’t think there has been a shelf collapse like this in East Antarctica since we’ve been able to receive satellite data,” Rob Larter, a marine geophysicist at the British Antarctic Survey, told CNN. “Conger is a very small ice shelf which has been decreasing in size for many years and this was just the final step which caused it to collapse.”

Antarctica is the coldest, iciest place on Earth, which makes the recent warming event particularly worrying for many scientists. Just a month ago, data showed Antarctica would set a record this year for lowest sea-ice extent — the area of ocean covered by sea ice around the continent.

Ice shelves like the Conger are extensions of land-based ice sheets and glaciers that jut out over the ocean. They help prevent those ice sheets from feeding ice unabated into the ocean.

When a shelf collapses, there tends to be an increase in the ice that flows from the land into the ocean, which leads to sea level rise— a phenomenon that threatens coastal communities around the world.

Ted Scambos, a glaciologist at the University of Colorado at Boulder and lead scientist at the National Snow and Ice Data Center, said the ice shelf’s collapse was likely a culmination of the record low sea ice conditions and the wave action hitting the shelf during the recent warm period, which was spurred by a strong winds from the warmer north.

Scambos said it could be a preview of what’s to come as the climate crisis eats away at the continent.

“Antarctica as a whole has kind of been locked away in an icebox,” he told CNN. “It’s been used to being surrounded by this fringe of sea ice; it’s been used to temperatures that are below freezing; and so those are big steps in terms of the kind of energy or the kind of processes that can happen to take away the ice from the edge of the continent.”

“And that’s what happened at Conger — and it’s an example of how Antarctica responds to these record events.”

Scambos said that for a long time the ice shelf had been wedged against an island, with the same effect as putting too much pressure on a piece of wood that later begins to splinter. Scambos said large rips had formed over time because of this pressure.

Scambos said the Conger’s collapse is another instance in which scientists get to observe what happens when an ice shelf is lost and a glacier is threatened.

“It’s not a very large shelf,” Scambos said. “But every time we’ve seen a shelf that is braced against an offshore island or even the coast of a bay, the glaciers behind it sense that there’s a back pressure, that there’s a force that’s resisting outward flow. In other words, they thin rapidly and they flow faster when the shelf is removed.”

Larter said that warming temperatures are making the collapse of ice shelves more likely. There has been a series of ice shelf collapses over the past 40 years, but those have mainly been in West Antarctica, which is warmer compared to the east.

Last year, for example, researchers discovered that the ice shelf holding back the Thwaites Glacier — also known as the “Doomsday glacier” — could collapse within the next five years. From their camp in the middle of the Antarctic to their stations on the coast, Scambos and a team of researchers flew over the gargantuan Thwaites Glacier, the size of Idaho, for two hours.

Scambos told CNN they could see “massive cracks in this ice shelf, places where the ice is tearing apart,” a clear sign of the Earth’s changing climate.

Larter said this happens less frequently in the East Antarctic because the ocean water there is much colder.

“The trend in East Antarctica is that the ice sheet loses some ice around the edges and it gains some in the middle,” Larter said. “Overall, it isn’t out of balance, but some on the outskirts are at a loss.”

A glacier that has been attracting scientists’ attention is the Totten Glacier, which could cause sea levels to rise by around 10 feet if its ice shelf collapsed.

Scambos said the recent record events in Antarctica are further proof of the speed at which the climate crisis is accelerating.

“It’s something that’s very hard to stop once it gets going,” he warned. “If we don’t put the brakes on, if we don’t slow this process down, then we’re in for very rapid rates of sea level rise probably before the end of the century.”

Scambos noted that children alive right now would be the ones that face these repercussions.

“And although I won’t be around to see it, there are people here with us today — they’re a little shorter than most of us — but they’re going to be there for that,” Scambos added. “And that means that we owe it to them to try to take care of this as soon as possible.”