A furious crowd gathered in central Seoul last month to protest against the policies of a man who isn’t even in power.

Waving signs and wearing white sashes emblazoned with the words “Vote for Women,” they accused presidential candidate Yoon Suk Yeol of attempting to appeal to anti-feminists to garner support ahead of the election.

“You don’t deserve to be a presidential candidate, Yoon,” the mainly female crowd chanted. “Go away.”

The protest highlighted how heated South Korea’s gender war has become ahead of the country’s March 9 presidential vote, with both leading candidates wading into the issue to win over young voters who are increasingly split along gender lines.

Facing a hypercompetitive job market and skyrocketing housing prices, anti-feminists claim the country’s bid to address gender inequality has tipped too far in women’s favor. Feminists, meanwhile, point to the country’s widespread sexual violence, entrenched gender expectations, and low female representation in boardrooms and in politics as examples of how discrimination against women is still rife.

Surveys show a growing proportion of young men are opposed to feminism – and conservative candidate and political novice Yoon is attempting to win their support. He’s promising to abolish the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family, which he claims is unfair to men, and raise the penalty for falsely reporting sex crimes. CNN approached Yoon’s office for comment on his gender policies but did not receive a response.

Meanwhile, liberal candidate Lee Jae-myung of the incumbent Democratic Party has tried to strike a more balanced tone. He says discrimination against men is wrong – an apparent nod to the views of anti-feminist men – but has also promised to close the gender wage gap.

He says he’ll keep the gender ministry – but change its Korean name so that it no longer includes the word “women.” But in the last few days of the election, he appears to have accepted that he won’t win the young male votes and is proactively courting online feminist communities.

In a statement to CNN, Lee’s office said he had created “many gender-related policies” for women and men, including a quota system for women to hold at least 30% for high-ranking public roles, benefits for new mothers and expanded support for paternity leave.

The heated election campaign has left women feeling as if the real issues facing them are being used for political point-scoring. And some worry that if Yoon wins the March 9 election, divisions between genders could widen even further.

The rise of anti-feminists

Since the brutal 2016 murder in Seoul’s trendy Gangnam neighborhood of a young woman targeted for her gender, South Korea has faced a reckoning over its attitudes toward women.

Activists pushed to address sexual harassment and widespread discrimination and found an ally in outgoing President Moon Jae-In, who vowed to “become a feminist president” before he was elected in 2017.

But in the years since, some men say the needle has moved too far. Anti-feminists point to statistics showing women are now going to university at a higher rate than men and say that compulsory military service for men gives women an advantage in the jobs market. Some place South Korea’s demographic crisis, caused by slipping birth rates, squarely at the feet of feminists.

While in other countries, anti-feminists might be discounted by politicians, in South Korea, these men have made themselves a powerful voter bloc.

Last April, Moon’s Democratic Party lost mayoral elections in both Seoul and its second largest city Busan, with exit polls showing young men in their 20s had overwhelmingly shifted their vote to the conservative People Power Party.

And in May the Korean marketing and research firm Hankook Research said a survey of 3,000 adults found that more than 77% of men in their 20s and more than 73% of men in their 30s were “repulsed by feminists or feminism.”

“There is a sense of exclusion among men,” said the 36-year-old writer Park Se-hwan, who identifies as anti-feminist. “It’s now time for us to discuss men in South Korea who in comparison have been largely ignored.” Park says he agrees with gender equality but says this feeling of neglect has garnered “a general objection to feminism” among young men.

According to Youngmi Kim, a senior lecturer in Korean Studies at the University of Edinburgh, social polarization and a lack of employment opportunities for young people has led to men in their 20s and 30s becoming more conservative.

Or, as Yun Ji-yeong, an associate professor in philosophy at Changwon National University, puts it: “Many people are realizing that the (country’s) scarce resources are being distributed very unequally.”

“When they’re looking for the cause, they point the finger at the women who are in front of them.”

The struggle facing feminists

To women, the fraught debate over gender isn’t just leaving them feeling like a political punching bag – they say it’s also plastering over the real issues they’re facing.

Just 15.6% of senior and managerial positions are held by women – significantly less than the US’s 42%. Less than 20% of legislators are women, again well below most OECD countries. Digital sex crimes are so pervasive that they affects the quality of life for women and girls, according to Human Rights Watch (HRW), and women continue to face sexism and pressure to meet unrealistic beauty standards.

Yang Ji-hye, a youth rights activist, says many of the anti-feminist movement’s claims are not supported by statistics – and she thinks the way gender is being talked about in the election is “absurd.”

“I’m sick of these anti-feminist politics – it makes me overwhelmed just to say how much women are being discriminated against, when at the same time they say there is reverse discrimination (against men),” she said.

Writer Park Won-ik says people with extreme views on both sides are engaged in a “cultural war.” He says it’s difficult for others to express their opinions without being threatened. “There’s no effort of keeping certain rules as good citizens or as civilized people, whether you’re feminists or not,” he said.

According to the University of Edinburgh’s Kim, Korea still has a “long journey ahead” in terms of gender equality.

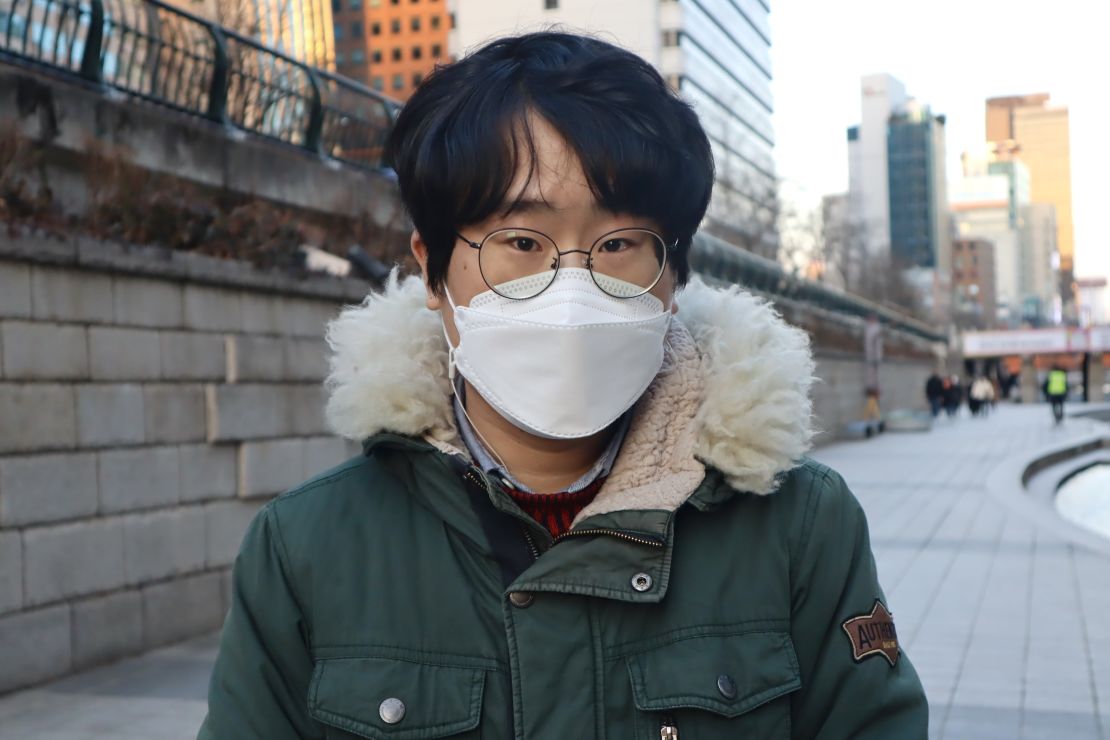

Kim Ju-hee, who was at the protests, has felt discriminated against for her gender – she’s been told her looks were part of her job of being a nurse, and at home her female relatives are still expected eat at a small table at the back of the house after ancestral rituals. She also feels frustrated about the way feminism has been used in the election.

“In this election, feminism is not viewed as an issue, but rather a token,” said Kim, 27. “I was very angry that it was used as if it was going to get discarded afterward.”

Yun, from Changwon National University, says if Yoon becomes president she expects feminists to face an even greater challenge for equality.

“Since the abolition of the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family is one of the most important promises, I think that it will probably be implemented as a tangible action first,” Yun said.

“In that case, I have a concern that gender conflict and women’s human rights may go further backward.”

CNN’s Pallabi Munsi and Saeeun Park contributed to this report.