Bob Galyen has spent his career building electric car batteries. And he thinks the United States has a problem.

Galyen, who engineered the battery for the General Motors EV1, the first mass-produced electric vehicle, and also served as chief technology officer at a Chinese company that’s the top battery producer in the world, isn’t the only one. Elected officials, automakers and customers in the US are all excited about the possibility of electric cars, and those cars will be key to the US meeting its climate goals.

Simply building and selling electric cars, or providing subsidies for the people who make and buy them, isn’t enough. Electric cars need batteries the same way combustion cars need fuel – and the metal in those batteries can be just as precious and hard to get as gas. People like Galyen are worried the US simply isn’t ready for that switchover, or doing enough to get ready.

The United States sources about 90% of the lithium it uses from Argentina and Chile, and contributes less than 1% of global production of nickel and cobalt, according to the Department of Energy. China refines 60% of the world’s lithium and 80% of the cobalt. Those metals are critical for electric vehicles.

Galyen said he’s struggled to get the United States to create a long-term plan for electric batteries, instead watching as priorities shift depending on what political party holds the White House. The Biden administration has pushed for electric vehicles, yet halted mining projects in Arizona and Minnesota that would boost domestic supply of electric vehicle materials.

“We have neither the raw materials nor the manufacturing capacity,” Galyen told CNN Business. “If the wrong country goes to war with us, we don’t have enough batteries to support our military.”

“China could shut down the world’s electric vehicle transition for political reasons,” Jeffrey Wilson, research director of the Perth USAsia Centre at the University of Western Australia, told CNN Business. “As of today, there’d be nothing we could do to stop that in the short term.”

Wilson pointed to the possibility of China restricting exports of lithium hydroxide to give its domestic electric battery and vehicle manufacturers an advantage. (Lithium hydroxide, which is critical for batteries, is largely processed in China.) He said that a 2010 incident when China restricted Japanese access to rare earth minerals during a dispute between the countries showed the risk isn’t out of the question.

Others say the national security risks that come with the shift to electric may be less than those posed by oil. It’s not in the best interest of foreign countries to restrict US battery supplies, some suggest.

“If China decided to pull the plug on [electric vehicles], batteries, and battery cells today, then there would be a huge problem for [the electric vehicle] transition,” Tom Moerenhout, a Columbia University professor who studies global energy policy. “But China has no interest in doing that.”

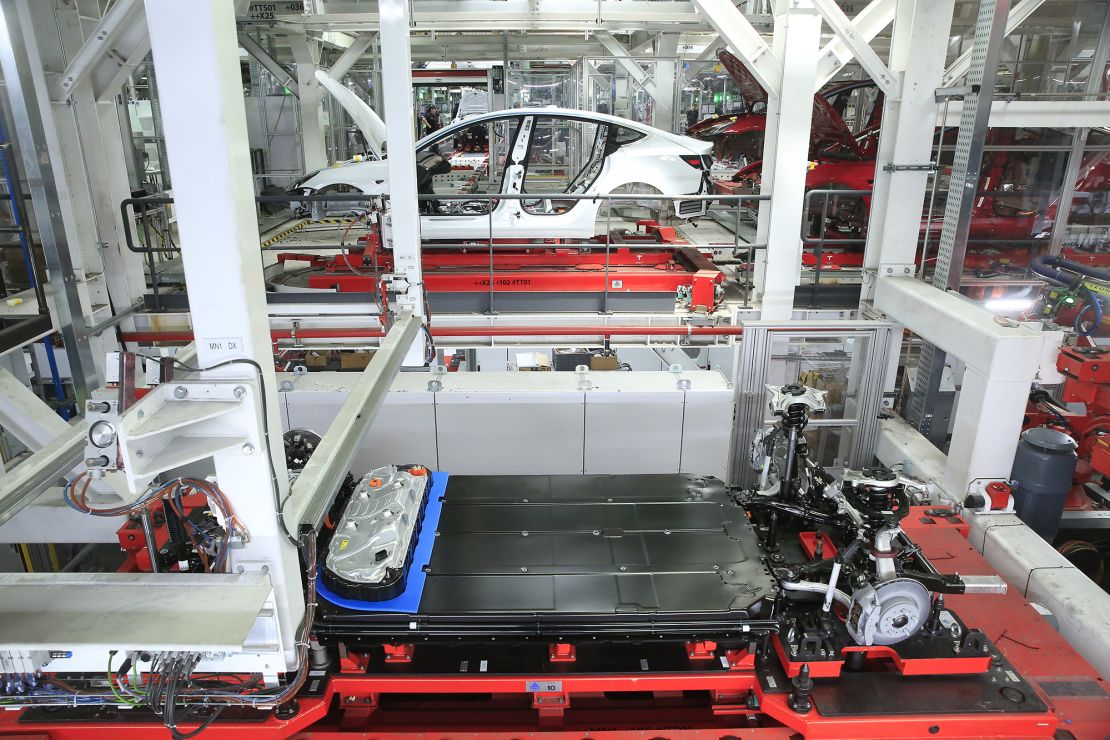

The rush for batteries

President Biden has called for 50% of vehicle sales to be electric by 2030, a goal that Ford and GM have echoed. California has said all new vehicles must be zero emission by 2035. The bipartisan infrastructure bill is investing $7.5 billion in electric vehicle charging.

“There have been a lot of bold things said that would be somewhat difficult to back up with the reality on the ground with raw material supply,” Francis Wedin, the CEO of Vulcan Energy, a lithium company developing a project in Germany, told CNN Business.

Mining experts say that the extraction and processing of battery metals has been largely overlooked. The popularity of electric vehicles hasn’t impacted how the US government treats mining, they say.

“You can’t win a football match with just a star quarterback. You got to have a whole team,” said Emily Hersh, the CEO of Luna Lithium, a mining startup that’s exploring projects in Nevada.

It can take seven to 10 years to get a mine set up, and sometimes longer.

Prices for critical battery metals prices like lithium, nickel and cobalt have spiked in recent months. Some automakers like Tesla have made deals with suppliers of raw materials recently, which may help insulate them from shortages.

The government has offered subsidies for electric vehicle purchases and charging infrastructure, but the mining sector hasn’t seen similar support, the battery metals experts say.

A challenge for US leaders is what to do when the country’s values come into conflict, including electrical vehicle adoption, environmental preservation and halting America’s historic mistreatment of indigenous people.

Last month the Biden administration canceled leases for a planned nickel mine in Minnesota, called Twin Metals, due to environmental concerns. Last year Biden slowed a copper mining project in Oak Flat, Arizona that the Trump and Obama administrations had previously pushed for alongside Congress. The Biden administration said it wanted to better understand the concerns of Indigenous people and environmental impacts.

Electric vehicle proponents say the technology is an environmental good. The vehicles have a smaller lifetime carbon footprint than traditional vehicles, unless they last only a few years. Electric vehicles have fewer emissions as there’s no tailpipe, leaving only brake pad discharge and tire wear. Electric vehicles also lessen the need for fossil fuels like gas.

But electric vehicle batteries rely on metals that are mined, like lithium, nickel, cobalt, copper and graphite. Mining in the US is often associated with its negative environmental impacts. The battery metals experts say the negatives are a tradeoff we must accept for a greater environmental good. They argue that the US has better mining standards than some foreign countries, so there are global environmental benefits of mining at home.

The Biden administration has largely avoided discussion of mining and its significance to electric vehicles. Biden made a brief reference to “metallurgy” in last year’s State of the Union, describing it as a job of the future.

A White House report from June 2021 called for resilient supply chains and acknowledged the security risk of the country’s shortcomings on batteries.

“Innovations essential to military preparedness—like highly specialized lithium-ion batteries—require an ecosystem of innovation, skills, and production facilities that the United States currently lacks,” the authors wrote.

Howard Klein, founder of RK Equity, an investment group focused on lithium, feels that the country has soured on mining, at its own expense.

“Lithium, nickel and graphite are clean energy metals,” Klein said. “If we don’t do this, the green agenda is goodbye.”

When risks are hard to size up and agree on

Historically, there have been examples of the “resource curse,” in which natural resource wealth contributes to negative impacts for countries, including corruption, violence and durable authoritarian regimes. Decades of US policy in the Middle East, for example, with its attendant support for dictatorships and warfare, have been argued to be largely motivated by abundant petroleum supplies in the region.

“Resource curse” concerns in this case could be most pertinent to Bolivia, which has a wealth of lithium reserves and has weaker political institutions than other battery-metal rich countries like Australia and Chile, according to Emily Kilcrease, a senior fellow in energy, economics and security at the Center for a New American Security, a Washington-based think-tank.

“I might argue that Chinese investments into lithium mines are a bigger threat to U.S. raw material supply chains, rather than political instability,” Kilcrease said.

Chinese companies own stakes in South American mining companies like Pilbara Minerals and SQM. Last year the Chinese company Zijin Mining bought Neo Lithium, a Canadian company with an Argentine lithium project.

For some national security experts, concerns about the electric vehicle supply chain are overblown.

Eugene Gholz, a Notre Dame political science professor who previously advised the Pentagon, said national security concerns over energy have been exaggerated before, like with oil. He believes that’s happening again. Gholz thinks the national security risk of electric vehicle adoption are small, and less than the oil supply chain.

“F-35s won’t fall out of the sky because we don’t have access to cobalt imports,” Gholz told CNN Business. “It’s not like you need to constantly deliver diesel to the forward operating base. Once the base has a battery, it’s got a battery for years.”

There are good reasons for China not to restrict US access to electric vehicle batteries. Doing so would damage its economy. China also depends on US allies like Australia and Chile to supply it with raw battery materials to refine.

He views warnings of national security and electric vehicles as a strategy to trigger government funding.

“We have confidence in very few institutions in the United States,” Gholz said. “The American people have confidence in the military. If you can say we have to do something to preserve the military, that has political resonance.”