This weekend, Javi Gomez is traveling nearly 500 miles from his native Miami to Florida’s capital in Tallahassee to plead his case against a piece of legislation LGBTQ advocates are calling the “Don’t Say Gay” bill.

He’s nervous. He’s ready.

In elementary school, classmates called him names for what they thought were feminine traits, like the pitch of his voice and his proclivity for hand gestures. His experiences are not unusual for a young LGBTQ person – 52% of LGBTQ middle and high schoolers said they’d been bullied either in person or electronically in the past year, according to a 2021 report from the Trevor Project, a suicide prevention organization for queer and trans youth.

Gomez, now a high school senior, blames his former classmates’ bullying on ignorance – they “didn’t know what they were talking about or what they were saying because it was all very learned from other people,” he said.

Some exposure to LGBTQ topics – what it means to be gay, queer or transgender, and why it’s wrong to discriminate against LGBTQ people – might have helped alleviate the pain they inflicted, he said.

“Now I look back on my past, and I’ve healed,” he said. “I’ve tried to forgive. But that still doesn’t mean there’s not a lot of trauma to it.”

It’s why he’s traveling so far to speak with legislators about “Parental Rights in Education,”identical bills introduced last month in Florida’s House and Senate, that would, among other things, prohibit school districts from “encouraging” discussion of “sexual orientation or gender identity” in elementary school classrooms.

The legislation is moving through Florida’s legislature – this week, it passed the Senate Education Committee. Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis has indicated his support for the bill, though there’s no timeline for when it could reach his desk. (The legislative session is up in a few weeks.)

Many opponents of the bill believe it will pass. And when it does, they say, the floodgates will open for lawmakers to introduce more extreme bills that curb the rights and freedoms of LGBTQ students. There is a lot of uncertainty about what the bill, if signed into law, would actually ban, given its broad language. But they say they fear for the children and teens attending schools where their identities put them under extra scrutiny and they face increased risk of abuse, especially when their homes may not be guaranteed to be supportive environments.

“It’ll probably reach the point where legislators are emboldened,” said Scott Galvin, executive director of Safe Schools South Florida, an organization that advocates for the safety of LGBTQ students. “The mind reels at what potentially could happen.”

Many advocates have called Florida home for decades: Galvin, a city council member in North Miami, remembers being the only gay kid in his Miami high school senior class. Brandon Wolf, press secretary at Equality Florida, moved to Orlando from Portland, Oregon, 14 years ago. They have watched the state’s LGBTQ communities grow and thrive, and also mourned the victims of the mass shooting at Pulse nightclub, whereWolf says some of his best friends were killed. They want these communities to continue thriving for generations to come and are fighting for LGBTQ people of all ages to feel safe in the state.

“We’re talking about rolling back very fundamental elements that we’ve worked so hard to make, and it’s not only disappointing and unfortunate, but it’s also terrifying for LGBTQ people who were just starting to feel comfortable in their home state,” Wolf told CNN.

Why LGBTQ advocates are speaking out against ‘Don’t Say Gay’

The Parental Rights in Education legislation introduces a few measures, including one that would require teachers to alert parents to issues relating to their children’s “well-being” and prevent policies that block parents’ access to “certain records,” according to the bill, though the types of records are not specified.

But the line that has caused the most distress among LGBTQ advocates reads as follows: “A school district may not encourage classroom discussion about sexual orientation or gender identity in primary grade levels or in a manner that is not age-appropriate or developmentally appropriate for students.”

According to the House bill’s co-author, Florida GOP Rep. Joe Harding, “primary grade levels” include kindergarten through third grade.

But the second half of that sentence – “or in a manner that is not age-appropriate” – has advocates worried the bill could be interpreted broadly enough that schools would deter instructors in any grade from discussing those topics with students.

“The ‘or’ could certainly be interpreted in a lot of ways,” Galvin said. “The vagueness of that sort of continuation of the sentence is to me what’s concerning, let alone shutting it down in the elementary age.”

Advocates fear the bill will keep students in any grade from learning about LGBTQ equality and the work it took to get there. They fear the legislation could erase important episodes in history like the massacre at Pulse nightclub in Orlando. And on top of that, discouraging discussion of LGBTQ topics could ostracize LGBTQ students whomay not feel comfortable discussing their identity if the bill passes and discourage students who are questioning their identity from exploring the topic at school, they said.

“Can you imagine having to concentrate in science or math class while knowing that those who are supposed to protect you refuse to, or are unable to do so because the law prohibits them from doing so?” said Roberto Abreu, an assistant professor in the University of Florida’s Department of Psychology whose research areas include LGBTQ communities.

Schools are already often hostile environments for LGBTQ kids – nearly 33% of LGBTQ students ages 13 to 21 said they missed a day of school over the course of a month because they felt unsafe or uncomfortable, and more than 77% said they avoided school functions because they felt unsafe or uncomfortable, according to the most recent National School Climate Survey published by the GLSEN (the Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network) in 2019.

The ignorance that Gomez was confronted with in elementary school is almost ubiquitous in schools nationwide. According to the GLSEN report, 98.8% of LGBTQ students said they heard “gay” used in a negative way, and more than 95% of them heard homophobic slurs while at school.

A group of LGBTQ students shared their stories of harassment with their school superintendent last month at Compass LGBTQ Community Center in Lake Worth. Speaking with Palm Beach County School Superintendent Michael Burke, the members of the youth group held each other’s hands for support as they recounted their stress over not knowing which bathroom to use, the teasing they endured in locker rooms and their fear of attending classes if the bill were to pass, Compass Center executive director Julie Seaver told CNN.

The superintendent was receptive, Seaver said, and left his contact information for the students gathered there. It was a positive meeting, she said, but she worries for students in areas where leaders aren’t working in their favor.

“Just think of the LGBTQ youth and students who are not in a more inclusive county like Palm Beach,” she said. “Just think of those kids – do they have anyone in their corner that’s supporting them?”

The bill is one of many in recent years

Last year’s nationwide roster ofanti-LGBTQ legislation was the largest in recent history, according to the Human Rights Campaign, and many of the bills targeted transgender youth. This year’s slate of bills may surpass the 2021 record, Wolf said.

His organization, Equality Florida, had successfully stopped every bill it deemed discriminatory against LGBTQ Floridians for its first 25 years of existence until 2021, when the “Fairness in Women’s Sports Act” passed, barring trans girls from competing on women’s sports teams at public secondary schools and universities in the state, he said.

This month, DeSantis said it was “entirely inappropriate” for school staff to discuss a student’s gender identity, though he said he didn’t think those conversations are happening in Florida “in large numbers.”

Wolf said it’s not surprising that conservative lawmakers are introducing bills aimed at LGBTQ residents, considering the considerable progress made in 2015 when the Supreme Court ruled that the Constitution guarantees the right to same-sex marriage and in 2020, when the Court ruled that federal civil rights laws protect LGBTQ workers from discrimination.

“It’s not surprising that we’re seeing backlash to advancements in LGBTQ equality,” he said. “It’s not as if opponents go home and shake hands and say, ‘Good game.’”

The bill’s co-author says the bill is meant to give parents a say

Florida Rep. Joe Harding, who co-introduced the House bill, said he was sympathetic to the challenges of marginalized students in the state but disagreed with opponents who said the bill could lead to more bullying or marginalization of those students.

He told CNN the bill is meant to deter school staff from inquiring about a student’s gender identity or pronouns without including their parents in the conversation. He said the experience could be confusing for young children.

President Joe Biden, by speaking out against the bill, Harding said, is effectively “saying it’s okay, for children as young as kindergarten, for someone within the school district to change their gender, change their name and be one person at school and be another person at home.

“As a parent, that is just shocking,” he said.

Harding said that he’d heard a few instances of parents complaining that school staff were discussing gender identity with their children without their input, though he didn’t get into specifics of where in the state these instances occurred.

When asked if he believes that a student changing their gender identity, name or pronouns at school is an inherently negative thing, Harding said the “negative thing is driving a wedge between the parent and student.”

“Nothing should be withheld from parents in a child’s life,” he said.

Parents would be able to sue school districts if they suspect a violation of the legislation, if the bill passes.

As to whether the bill would stop a teacher from answering students’ questions about gender identity or sexuality, Harding said the legislation is “not discouraging that.”

“Students are going to ask teachers questions of that nature,” he said. “[Teachers] know when it’s time to engage the parent.”

Harding said the point of the bill is to fully involve parents in their children’s schooling, and that nothing about a child’s mental health, academic performance or other private matters should be withheld from their guardians.

But cluing parents into conversations about a child’s identity isn’t always beneficial to that child’s wellbeing, Abreu said.

“Unfortunately, sometimes parental figures are not the safest person for LGBTQ youth to come out to,” Abreu said in an email to CNN. “What this bill requires schools to do, involve parents in every private matter in their child’s lives, could place LGBTQ youth at risk for … increased symptoms of depression and suicidal ideation, and homelessness as a result of being expelled from their home.”

Because students spend so much of their waking hours in school, it’s “not surprising that LGBTQ youth often find at least one supportive person within their school environment,” Abreu said.

Brian Kerekes, a math teacher in Osceola County and a board member representing the state in the National Education Association, told CNN he’s had conversations with students in which they’d disclose their preferred name and pronouns, which he’d then use in his classroom.

But when he’d meet with their parents to discuss their grades and used their child’s preferred name, he’d find some of their parents weren’t supportive of their identity, said Kerekes, who penned an opinion piece last year about his experiences as an LGBTQ teacher in Florida public schools.

That’s relatively common nationwide: One in three LGBTQ young people said they found their home to be LGBTQ-affirming, according to the Trevor Project’s 2021 National Survey on LGBTQ Youth Mental Health. By contrast, 50% of respondents said they found their schools supportive of their LGBTQ identity.

“First and foremost as educators, our job is to provide a safe space for our kids to learn,” Kerekes said. “I feel that this bill is going to put us at odds with that.”

Miami high school student Gomez said it wasn’t until he found out one of his teachers was gay that he started to experience something that felt like confidence. It was a “turning point” in his life, he said, meeting a self-assured role model like his instructor.

Where LGBTQ Floridians go from here

Whether the bill passes, LGBTQ advocates told CNN that they’re concerned about its repercussions in Florida’s thriving queer communities, like Orlando and Miami. LGBTQ people have built those areas over decades. They’ve served in leadership roles within those communities for years – Orlando has had Commissioner Patty Sheehan, the first out gay elected official in central Florida, according to the city, since 2000, and Galvin has served on North Miami’s city council for almost as long.

And they want the next generation of LGBTQ Floridians to build on their progress – not to rebuild completely. Gavin and Wolf said Safe Schools South Florida and Equality Florida are looking at legal challenges should the legislation pass, and Equality Florida has already traveled to Tallahassee with a crew of transgender teens to plead their case to legislators. The Compass Center offers programs for LGBTQ youth and their parents to meet with each other and with leaders in their community to share their experiences.

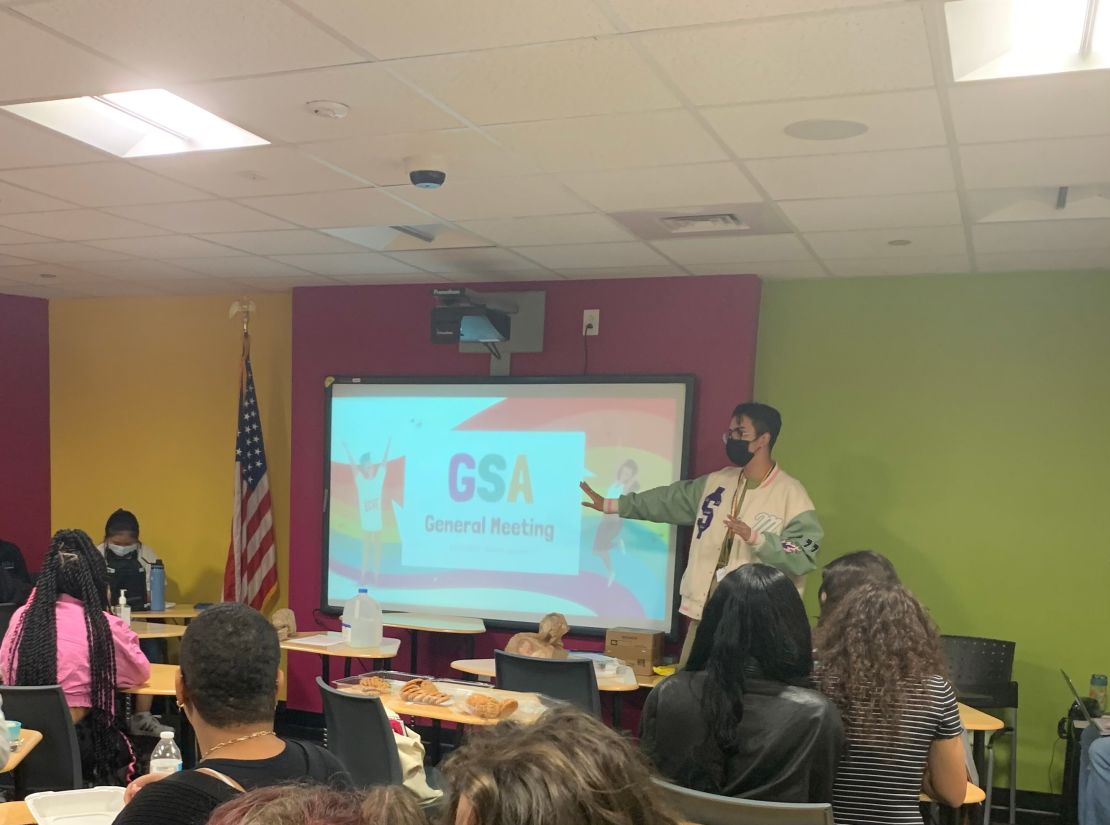

Young people like Gomez are fostering those communities within their schools. He’s the president of his high school Gay Straight Alliance, or GSA, and leads after-school courses on queer history and ballroom culture, seminars with doctors on safe sex, and viewing parties for “Pose” and “Legendary,” series that star queer and trans people of color.

While Gomez has spoken at rallies for LGBTQ rights, he’s never done anything like the lobbying he’ll do in Tallahassee. He’s going, he said, to “represent all the little queer kids” in the state experiencing what he did in elementary school.

If the legislation passes, Gomez said he’ll still reach out to lawmakers, call on allies and adults with LGBTQ loved ones to speak out, and continue seeking out and creating safe spaces for young queer and trans people, like he did at his high school.

“This battle is only beginning,” he said.