America is finishing the year with decades-high inflation. That doesn’t bode well for 2022.

Prices have climbed so high it will take some time for them to come back down to earth. In other words, the uncomfortable inflation numbers of 2021 will likely stay with us well into the New Year.

The most recent price data we have is from November, when two of the most watched inflation measures — the consumer price index and the personal consumption expenditure index — each climbed to a 39-year high.

The latter index is what the Federal Reserve pays the most attention to when assessing the nation’s inflation.

There’s some room for optimism: The central bank, which is tasked with keeping prices stable, is rolling back its pandemic stimulus and is expected to raise interest rates next year to tame inflation and stop the economy from overheating.

And last month’s data actually showed that prices increased at a slower rate in November than in October for both the CPI and the PCE indices. That’s good news, even though the slowdown was small at only 0.1 percentage points.

But here’s the thing: Economists prefer to look at price movements over a period of time, usually 12 months. So a small slowdown like November’s won’t move the needle just yet.

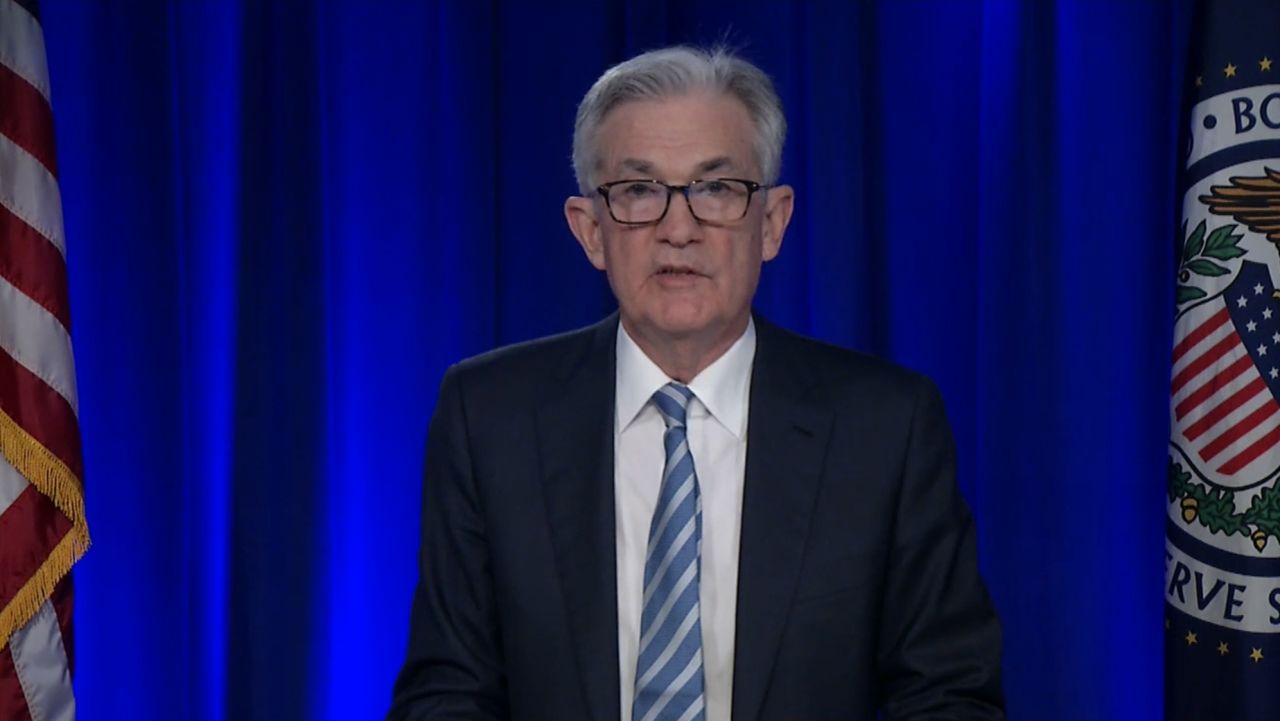

In fact, it might take months for these incremental slowdowns to show up in the data. After a year of prices soaring on high demand and supply chain chaos, a lot of big numbers are baked into the 12-month data set. Even if inflation suddenly falls off a cliff, it would take time for the leading indices to reflect that. This is what Fed Chair Jerome Powell is talking about when he mentions “base effects.”

Why will inflation remain high?

Several factors are keeping prices elevated.

One is the supply chain chaos that came to a head last summer. Even though some bottlenecks have eased, the issues are not fully resolved. And as long as it’s more expensive — and takes more time — to move goods around the world, higher transport costs will likely be passed down to consumers.

Another big contributor is the high cost of commodity prices, leading to surging energy and food costs. Prices in both sectors have soared this year and added a good chunk to the inflation we have already seen. In the case of food, high prices have forced some consumers to buy less or switch stores.

Economists don’t expect that to get any better next year. Aside from high demand and shipping costs, rising prices for fertilizer and continued bad weather could keep food prices high even as other pandemic fueled inflation pressures ease.

Rising rents also remain a concern. This is important because housing represents a big percentage of what people spend money on. If rents eat up a bigger piece of the pie, consumers might wind up spending less, which would be bad news for the recovery.

In November, rent rose 0.4% for the third month in a row, according to economists at Bank of America, and that points to higher and more persistent inflation going forward.

The “recent broadening of inflationary pressure has coincided with a notable pickup in rental inflation,” said Peter B. McCrory, economist at JPMorgan, “which jumped to its highest monthly rate in 20 years in the September CPI report and has stayed firm since then.”

And then there’s Omicron.

Several countries, including the United States, have seen record high Covid-19 infections in recent weeks because of the rapidly spreading variant. If this leads to a new round of lockdowns, it could once again change the way consumers spend and boost demand for stay-at-home goods.

Perhaps more importantly, Omicron could impact energy prices: If restrictions return and people travel less, the lowered energy demand would mean prices ease, and that would help bring inflation back down.