(CNN)Serious cooks may quibble about the best way to sear a steak or bake a cake. But on one point, there is virtually unanimous agreement: To make food taste good, you've got to have salt.

Without salt, we would be "adrift in a sea of blandness," wrote Samin Nosrat in her seminal tome, "Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat," noting that "salt has a greater impact on flavor than any other ingredient."

Salt "coaxes out flavors in a pan and awakens the taste of just about anything it touches," said Steven Satterfield, the James Beard award-winning chef of the farm-to-table restaurant Miller Union in Atlanta. Aside from amplifying the natural flavors of foods, he said, salt can suppress bitter compounds such as the spice from a raw radish and expose the vegetable's hidden sweetness.

In recent weeks, the US Food and Drug Administration has reminded us of another truth about sodium, which many of us get from salt: The average American consumes way too much of it ŌĆö about 3,400 milligrams a day. (For healthy adults, the recommended daily limit for sodium set by federal nutritional guidelines is 2,300 milligrams ŌĆö the equivalent of about a teaspoon of table salt.) Excess has been linked to heart attacks, stroke, kidney disease and other chronic ailments, adding to the burden of US health costs.

Yet salt and sodium are not the same thing. The salt we consume, a crystal-like compound whose chemical name is sodium chloride, is a major source of sodium in our bodies, a mineral necessary for proper muscle and nerve function, hydration, regulating blood pressure and other biological processes. To put it another way, we need a certain amount of salt to survive. Determining how much is the tricky part.

For those at high risk of hypertension, the American Heart Association advised aiming for 1,500 milligrams.

The biggest culprit, though, isn't the saltshaker. Around 70% of the sodium in Americans' diets is hidden in commercially processed foods and restaurant meals, according to the FDA. To help people better manage their intake, the agency on October 13 called upon the food industry to voluntarily reduce the sodium in 163 categories of their products.

The aim is to see a 12% sodium reduction in the overall population over the next two and a half years. That will still be above the 2,300-milligram target limit, but registered dietitians such as Carly Knowles recognize the wisdom behind that approach.

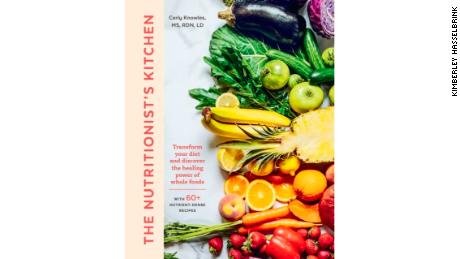

"Most of my patients are busy professionals or parents of young children who either don't have time to cook or don't like to cook," said Knowles, who is also a private chef, licensed doula and the author of "The Nutritionist's Kitchen" cookbook. "Since most sodium comes from commercially prepared and highly processed foods like frozen pizza, canned soups, burgers, and flavored snacks, my biggest challenge is to help them find healthy alternatives that don't require too much time to make and still taste good."

Cooking food at home, reading labels and trying new tastes are all effective strategies for lowering your salt intake, she said. Salt-free seasoning blends made of herbs and spices can also help, she added.

Fat naturally carries flavor, and Knowles suggested adding a small amount of a healthy fat source to your food just before serving, such as a spoonful of nut butter in your oatmeal or a drizzle of olive oil over your chicken.

Most important, though, is building a diet around unprocessed or minimally processed whole foods. Even though there is naturally occurring sodium in some of those foods, such as cow's milk and beets, the amount, she said, is typically very small, especially when compared to processed foods such as commercial bread and deli meat. And they are also great sources of potassium, as are other natural foods, including bananas, legumes, baked potatoes, avocados and seafood.

Potassium moderates blood pressure along with other electrolytes such as sodium, Knowles said. And most people don't get enough. So, increasing your potassium intake, while reducing sodium, can do double duty in helping lower blood pressure.

But be wary of turning to commercial salt substitutes that swap sodium chloride with potassium chloride. As the Cleveland Clinic website points out, besides having a slightly metallic taste that some find objectionable, they can raise blood potassium to risky levels in people with kidney disease and other medical conditions.

No ingredient can truly mimic the taste of salt, said Nik Sharma, a molecular biologist-turned-food writer who devotes a chapter to exploring how saltiness works in his critically acclaimed 2020 cookbook, "The Flavor Equation: The Science of Great Cooking Explained." "But there are ingredients you can add that distract the mind from looking for salt." A squeeze of lemon, a splash of an interesting vinegar, a spoonful of tamarind paste or a broth made of umami-rich dried shiitake mushrooms are among his favorites.

Cooking techniques such as roasting, grilling, searing and smoking can also add layers of complex flavor. Sharma has even discovered that some dishes that normally call for salt taste better without it.

Here are some other easy switches to consider for cutting sodium, without cutting flavor.

1. Go easy on the bread

Breads and pastries are one of the biggest contributors to sodium overload. A large roll or two slices of bread can contain upward of 300 milligrams. There are healthier ways to satisfy your starch cravings. A plain baked potato is low in sodium and one of the best sources of potassium around. Knowles recommends exploring the myriad varieties of nutrient-packed whole grains with appealing textures and flavor that have become increasingly available to consumers, such as organic barley and quinoa.

2. Move hearty veggies to the center of the plate

Sodium levels for meats, chicken and seafood are all over the map ŌĆö some relatively low if it's fresh and natural; some shockingly high if it's been injected with sodium-containing solution, as is often the case with supermarket chicken. Read the label or ask the butcher. Most fruits and vegetables, however, have little to no sodium, few calories, and loads of other nutrients. Satterfield finds creative ways to maximize their flavor with herbs, spices, acids and cooking techniques that make it easy to cut back on the salt. And by tossing in some nuts for protein, you probably won't miss the meat, either. Add some plain brown rice or other healthy grain and call it a meal.

3. Instead of canned or bottled tomato products, use fresh

Ketchup, tomato paste, tomato sauce, canned tomato soup, commercial spaghetti sauce and bottled salsa are all handy shortcuts for flavorful meals. They also tend to be loaded with sodium, unless you go with a low-salt or no-added-salt variety. But a large fresh tomato, or a cup of cherry tomatoes, contains less than 10 milligrams, not to mention a host of other nutrients, and contains no corn syrup or other additives to make up for the sodium loss.

4. Build a better salad

Bottled salad dressings can drown a bowl of nutritional goodness in salt and other not-so-good-for-you things in a flash. Try dressing your greens with extra-virgin olive oil and vinegar (or a squeeze of lemon) directly in the bowl instead. No need to measure, just figure on about a 3:1 ratio of oil to acid. The more flavorful your greens and olive oil, the less salt you'll likely be tempted to use. Adding fresh herbs, citrus zest, toasted nuts or fresh or dried fruits to the mix will also boost flavor without the need for salt.

5. Instead of sugary boxed cereal, start your day with oatmeal or another hot cereal

While instant oatmeal is high in sodium, regular or quick cooking has none. Boost the flavor and the nutrients by topping with fresh or dried fruit, toasted nuts, brown sugar or honey or roasted nuts.

6. Make your own spice blends

There are many commercial herb blends on the market now, but it's simple and cheaper to make your own with whatever's in your spice rack.