Internal Supreme Court documents that could enhance public understanding of the Bush v. Gore election battle and other significant cases of the late 1990s and early 2000s were to be opened last year under a deal forged by a long-serving justice, but the high court has delayed release of the materials, citing the pandemic.

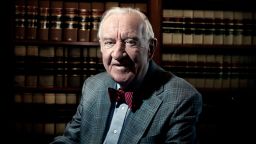

The late Justice John Paul Stevens, whose tenure spanned 35 years, planned for most of his case files to be opened and “freely available” at the Library of Congress by October 2020. His arrangement with the library – the details of which have not been previously reported – covers cases up to October 1, 2005.

Along with the 2000 Bush v. Gore decision that continues to reverberate in election-law controversies, the trove would include documents related to two groundbreaking gay-rights decisions, a seminal University of Michigan affirmative action dispute and several post-9/11 Guantanamo detainee appeals.

The release of once-private files can help illuminate one of the country’s most secretive institutions, even as the open files often spawn tensions among still sitting justices. The justices keep many of their procedures confidential and all their negotiations occur behind closed doors. Historians, law professors and journalists mine the papers to understand how the nine operate.

The files, which typically include draft opinions and memos written among justices, can shed light on the strategies of individual justices and nature of deliberations, why some appeals were taken, others rejected, and whether justices may have switched votes in cases heard. Such behind-the-scenes vote changes have made a difference in abortion disputes as documents from other justices’ collections have revealed.

The new Stevens files could reveal private conversations around a separate social policy dilemma, related to LGBTQ rights. He was the senior justice in the majority when the court in 2003 struck down a Texas ban on private sexual conduct between gay adults, and earlier in 1996, when it blocked a Colorado measure that prevented cities from passing antidiscrimination laws to protect gay people.

Yet archives that augment the historical record have in the past created internal conflict.

In 1993, when the papers of Justice Thurgood Marshall were opened at the Library of Congress just months after his death, then-Chief Justice William Rehnquist became furious with Library officials, questioning whether Marshall indeed wanted all his files opened so quickly. Rehnquist wrote a letter of rebuke to then-Librarian of Congress James Billington on behalf of the court majority.

Rehnquist had tried but failed to induce all eight associate justices to sign the letter, but in the end had to say he was writing for a “majority of the active Justices.” Some of the justices who declined to join in said they believed Marshall had wanted his papers to be released after his death.

Marshall indeed had set the terms of the release of the materials that covered his tenure through 1991.

Rehnquist also tried, unsuccessfully, to persuade colleagues to agree for the future to withhold private documents for set periods, for example, as long as all justices with whom an individual served had retired or died.

The files of Justice Harry Blackmun, later turned over with his archive to the Library of Congress, show that Justice Sandra Day O’Connor strongly agreed with Rehnquist in 1993 that the justices should set timelines for the release of papers. According to Blackmun’s notes, the vote was 6-3 and Rehnquist did not want to impose any rule without unanimity.

The three justices who voted against the proposed limits were Blackmun, Stevens and Justice Antonin Scalia, who died in 2016 and whose files are now housed at Harvard but closed for the near future.

The Supreme Court public information office said Stevens’ papers were still being organized for transfer and that the Covid-19 pandemic had slowed the effort. Library officials said they have no date for when the materials would be turned over. Once in hand, the library would sort and catalog the materials for public access.

Stevens, who died in 2019, finalized the agreement for his papers with Librarian of Congress Billington on January 3, 2005, Library officials told CNN. A supplemental agreement was signed on April 20, 2010, which happened to be the day Stevens turned 90 and the year he retired. He was the third longest serving justice in court history. (Billington died in 2018.)

The opening of justices’ archives flow from special arrangements by individual justices with the Library of Congress and various universities.

The late Justice Blackmun arranged to have his extensive files opened in 2004. That move further riled sitting justices. Blackmun had saved just about everything he ever wrote or received from a colleague.

Under court practice, a justice sends copies of memos directed to an individual justice during case negotiations to the whole group. Some justices plainly want greater control for posterity over the correspondence they write.

Justice Stephen Breyer, in a recent conversation with CNN related to his new book, “The Authority of the Court and the Peril of Politics,” said he had not yet decided whether to turn his papers over to a library.

Breyer said the justices have an “informal understanding” that certain documents, such as draft opinions and memoranda among justices, would be withheld from public view until after the death of other justices who served on the cases. Breyer acknowledged that such a pact might conflict with individual justice’s wishes regarding their papers.

The court’s Public Information Office did not respond to questions about whether any formal or informal agreement for the release of confidential files is in place under Chief Justice John Roberts, who succeeded Rehnquist in 2005. The PIO also declined to answer questions related to any screening of Stevens’ files or possible removal of documents.

Susan Stevens Mullen, a daughter of the late justice, said she was not concerned about any culling of his files. In an email exchange with CNN, she attributed the delayed transfer of her father’s materials “to COVID and the impact that closures and work-from-home has had on final review and organization of the papers.”

The Library of Congress is also awaiting the transfer of files belonging to the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Court officials said that release has also been slowed because of the pandemic. Although Ginsburg’s case files are all scheduled to be housed at the Library, case files will be closed to most researchers as long as any justice who participated in the decision in the matter is alive.

Stevens’ role in a historical age

Stevens, a 1975 appointee of Republican President Gerald Ford, was known for an independent approach and became a leading liberal of the bench. The Chicago native whose work in Naval intelligence during World War II earned him a Bronze Star, had lone legal career, beginning with a Supreme Court clerkship in 1947-48, then becoming a specialist in antitrust law, before appointment to a US appellate court seat in 1970 and then the Supreme Court.

He retired at the age of 90 and continued to write books and essays until his death at age 99.

Stevens put no restrictions on his files for the Library of Congress beyond separating them into two categories: materials created before October 1, 2005, and materials created on or after that date.

The first set was to be made available “after the first Monday in October in the year 2020,” which would have been October 6. (Stevens’ case files through 1984 can be viewed by researchers at the Library; those cover much of the ground in the files of other justices; the late 1990s and early 2000s material would likely be of most value to researchers and the broader public.)

The latter batch after 2005, coinciding with when Roberts became chief justice, would not become available under the Stevens’ agreement until “the first Monday in October in the year 2030.” (The justices begin their annual sessions on the first Monday in October.)

Stevens declined to condition the release of case files on whether justices who participated in the cases were still alive, and the gift agreement includes no exceptions or exclusions regarding the material to be donated, Library officials said.

That means his files would contain correspondence with sitting Justices Breyer and Clarence Thomas and with retired living Justices O’Connor, David Souter and Anthony Kennedy. The materials would also include the work of relatively recently deceased justices Ginsburg (who served 1993-2020), Scalia (1986-2016) and Rehnquist (1972-2005).

Those eight justices and Stevens decided the 2000 Florida election dispute between then Texas Governor George W. Bush and then Vice President Al Gore. Their 5-4 decision, ensuring that Bush won the White House, hung over last year’s election as the Donald Trump’s legal team tried to rely on some of its reasoning to challenge state election practices and final results that showed Joe Biden won the presidency.

Stevens, the court’s senior liberal at the time, dissented in Bush v. Gore along with the other justices on the left. In the wake of the September 11, 2001, terror attacks, Stevens, alternatively, was able to seize the majority for decisions that limited President Bush’s assertion of executive branch power and ensured some protection for detainee rights.

Stevens also led the majority in two important gay rights cases: the 1996 Romer v. Evans and 2003 Lawrence v. Texas. The papers could help explain his strategy that included assigning both cases to Kennedy, who became the voice of the court on LGBTQ interests in the years that followed, including to declare a constitutional right to same-sex marriage in 2015.

Another major case Stevens shepherded during this era was Clinton v. Jones, in which the court ruled unanimously that then-President Bill Clinton could not invoke presidential immunity to avoid a civil lawsuit for alleged sexual misconduct.

The approach Stevens negotiated for his archive donation to the Library of Congress largely follows that of Marshall (1967-1991) and Blackmun (1970-1994) at the Library of Congress and Justice Lewis Powell (1972-1987), whose materials are housed at the Washington and Lee Law School.

Once those files were opened, researchers could readily find documents involving still-sitting justices.

Library of Congress spokesman Brett Zongker said the Library has been in contact with the Supreme Court regarding timing for a transfer of Stevens’ materials, but no date has yet been given.

Processing and cataloging of files would occur at the Library, and Zongker said it was difficult to estimate how long that would take. He said that first nine years of Stevens’ files, through 1984, were received more than a decade ago and took less than four months to process.

However, Zongker wrote that, “The Library anticipates that the remaining portion of the collection will include a greater variety of papers … relating to his entire life as well as Supreme Court case files, dockets, and other material covering” Stevens’ subsequent decades on the bench.