The US, UK, France, Germany and European Union will help fund South Africa’s transition away from coal, in a multilateral effort that could serve as a model for other developing nations to ditch the fossil fuel.

The announcement on Tuesday provided a semblance of hope at the COP26 climate talks in Glasgow, Scotland, where the mood has been low after the G20 leaders’ summit failed to put an end date on the use of coal, as some member countries and the COP26 presidency had sought to do.

Prime Minister Boris Johnson of the UK said the initial $8.5 billion partnership would help South Africa to decarbonize its coal intensive energy system. The details of the specific funding were not announced, and diplomats expect the fine print to be worked out in the months ahead.

US President Joe Biden stressed that trillions in public and private funding will be needed to help the developing world move away from fossil fuels.

“By assisting and responding to the needs of developing countries, rather than dictating projects from afar, we can deliver the greatest impact for those who need it the most,” he said.

Climate scientists and some diplomats say the South Africa agreement could pave the way for similar deals with other heavily-polluting developing countries – a critical step in containing global warming and avoiding a full-blown climate catastrophe.

The promise to finance a transition from coal will be noticed by politicians in developing nations because South Africa is among the most coal-dependent nations in the world.

A key sticking point at the COP26 talks is climate finance. There is a Global North-South divide at COP26 over the broken promises of wealthy countries to transfer $100 billion a year to the developing world to aid its transition to low-carbon economies.

The $100 billion target was missed last year and a large gap remains. Experts say $100 billion a year isn’t enough to begin with.

Prior to COP26, only a small number of developed nations were paying their fair share on climate financing for poorer countries, according to independent think tank ODI.

World’s most polluting company

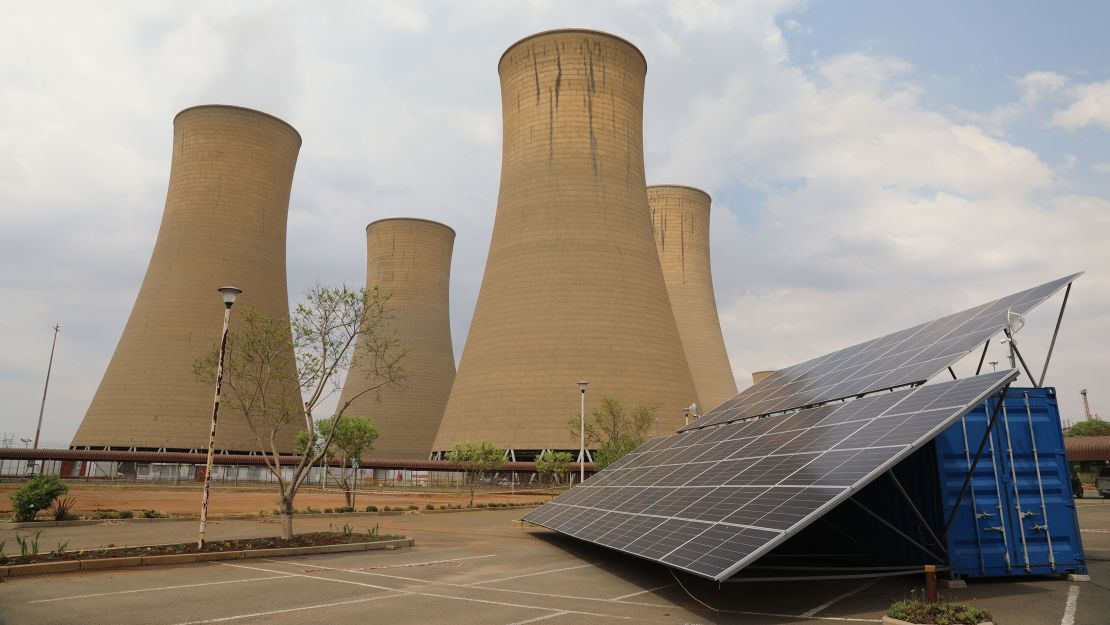

Nearly 90% of South Africa’s power generation is fueled by coal, making the country one of the heaviest polluters per-capita on the planet.

South Africa’s Mpumalanga province is home to most of the country’s coal industry and coal-fired power stations, with their colossal chimneys, flanking both sides of the highway.

Driving east from Johannesburg to the province, the coal mines appear almost as soon as the neighborhoods recede.

Recently, the Center for Research on Energy and Clean Air judged Eskom – which has a monopoly on power in South Africa – to be the world’s most-polluting power company. It spews more deadly sulfur dioxide than the US, Europe, and even China’s power sectors.

But the group CEO of Eskom, André de Ruyter, thinks that the company’s track record on emissions is an opportunity for wealthy nations. They are explicitly backing a transition to cleaner energy and have made significant promises in coal reductions already. But someone has to pay for it.

“The cost of mitigating a ton of carbon in South Africa is a fraction of what mitigating that carbon would cost in the US or Europe,” de Ruyter told CNN in an interview. “If you have a limited amount of money to combat climate change, then coming to a country like South Africa and incentivizing us to remove carbon emissions makes absolute sense.”

The cost of reconfiguring the distribution to access green technology will run into the tens of billions of dollars, said de Ruyter.

After years of mismanagement and allegations of corruption, Eskom has colossal levels of debt running more than $25 billion and, by most estimates, South Africa has plenty of coal left in the ground.

And even prior to the deal, South Africa had committed to transitioning to renewables, a political commitment that helped woo the US, UK and EU.

“There is a saying that the Stone Age didn’t end because of a lack of stones. I’m convinced that, given the current technological trends, the coal age won’t end because of a lack of coal,” de Ruyter said.

But it could stretch out because of a lack of jobs. Like much of proposed climate action, local political realities are where green power initiatives will live or die.

The Minerals Council, an industry lobbying group, says that around 450,000 households in Mpumalanga province alone depend on coal for their livelihoods. With official unemployment hovering at around 34%, a significant loss of jobs in the sector would be politically dangerous for the ruling ANC.

“You are not going to be able to replace all of the jobs that coal and ash were able to generate, because you need a lot more hands and generally lower skilled people with that,” said Marcus Nemadodzi, the general manager of the Komati power station.

Nemadodzi points to the one remaining unit generating power at the aging power station. The government mothballed Komati in the 1990s, but brought it back online as Eskom struggled, and still struggles, to provide reliable electricity to homes and businesses.

Soon, it will be shut forever, with some resources shifted to manufacture small scale solar based power for rural electrification.

“This is going to be a process. We are not switching off one and the next morning there will be another, but we have to start somewhere,” Nemadodzi said.

In a press conference in late September, South African President Cyril Ramaphosa told CNN that a just transition is a necessity, calling it a ‘gradual process.”

“We want those countries from more developed economies who caused so much damage to the environment to live up to the commitments and the promises that they made through the conferences that have been held,” he said.

Even though far more funding will be needed to move South Africa fully to renewables, the UK High Commissioner to South Africa called the emerging deal to help finance the country’s ambitious renewable goals a significant moment.

“If we are to keep alive the goal of limiting the increase in global temperature to 1.5 (degrees) developed economies must work in partnership with major developing countries and emerging economies to deliver a just, inclusive and accelerated transition away from coal, and the development of a sustainable, green, and growing economy for all. This agreement shows how it can be done,” said Antony Phillipson.

Part of the political commitment in South Africa comes from the realization that this corner of the globe will be hammered by the consequences of the climate crisis, with more frequent droughts and faster rising temperatures expected in much of Southern Africa.

On a global scale, it won’t be enough for the biggest emitters like China and the US to curb emissions. Climate scientists say that almost every emitting nation will have to play a part to avoid untenable temperature rises.

But if your very survival is based on coal, you have a very different perspective.

Eighty-four steps down into a disused mine near Ermelo, the illegal miners use pickaxes and shovels to scrape out coal to sell for stoves and heat across the province. Sometimes, they say they sell to middlemen who sell the coal to Eskom.

Anthony Bonginkosi braves the threat of rock falls and deadly gasses to feed his grandmother and sister. He has heard about the promise to stop using coal.

“I don’t have a choice; I have to save my hunger. Not only me, but those who follow me,” he said. “What can I say about that. It makes me scared. We have a lot of people who depend on coal. So we can’t live without it.”