The Supreme Court was more than two hours into arguments over a Texas abortion law when Justice Elena Kagan ignited the tension that had been slowly building in the courtroom.

“The actual provisions in this law have prevented every woman in Texas from exercising a constitutional right as declared by this court,” she said, her voice rising as she pressed Texas Solicitor General Judd Stone. “That’s not a hypothetical. That’s an actual.”

Monday’s paired hearings before the justices, still relatively new to the courtroom after pandemic isolation, offered an up-close look at their views on the unprecedented Texas law that prohibits abortions after about six weeks of pregnancy. The law attempts to shield state officials from federal lawsuits by empowering private citizens to enforce the ban.

The extraordinary session was, in essence, the start of a conversation the nine justices will continue in private as they begin to resolve the knotty case. Their respective emphases were on display during the give-and-take.

Kagan, one of the three remaining liberals on the bench, cut through the procedural intricacies and legalese to try to steer the conversation and offer an option for a compromise ruling.

Justices Samuel Alito and Neil Gorsuch were most forceful from the conservative side, voicing skepticism for arguments against Texas from abortion clinics and the US Department of Justice.

Seemingly most consequential were the remarks of Justices Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett, two conservatives who had earlier voted to let the law take effect, as they expressed doubts regarding Texas’ effort to prevent federal lawsuits against the law that flouts the Supreme Court precedent.

Kavanaugh appeared concerned that if a state could forbid federal challenges to an obviously unconstitutional abortion law, it could do the same for measures related to gun rights or free speech. Barrett focused on the limits of Texas state courts, alternatively, to fully air and resolve constitutional claims related to the ban.

All told, it appeared that a court majority was ready to rule against Texas for the first time and allow at least one of the lawsuits to proceed, and perhaps soon suspend the ban. In place since September 1, the new law conflicts with high court precedent dating to 1973’s Roe v. Wade and has forced women throughout Texas to travel to Oklahoma and other neighboring states for abortions.

RELATED: Overturning Roe could mean women seeking abortions have to travel hundreds of miles

The importance of working in person

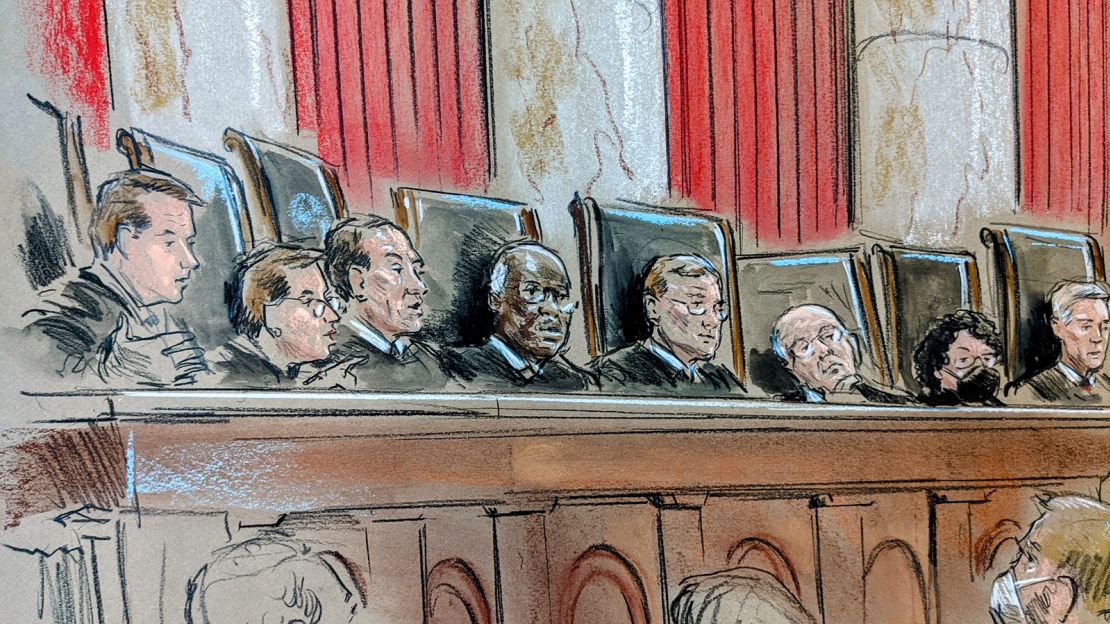

The proceedings Monday demonstrated the value to the justices of their return to their crimson velvet and white marble setting. As they questioned the various lawyers, they hung on one another’s words, picking up lines of inquiry, reinforcing and countering one another.

The justices have been back on the bench for about a month, and only a limited number of spectators – law clerks, news reporters, justices’ guests, all masked – are allowed in. On Monday, Jane Roberts, wife of the chief justice, and Joanna Breyer, wife of senior liberal Justice Stephen Breyer, attended.

The session began on a commemorative note, as Chief Justice John Roberts observed that the court had held a ceremonial investiture for Justice Clarence Thomas exactly 30 years ago Monday, and he then welcomed new US Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar, a former assistant SG who earlier this year had served the Biden administration in the top job in an acting capacity.

Soon after, tensions built, as the justices went an hour longer than their planned two-hour session.

“The entire point of this law, its purpose and its effect,” Kagan said in one of many pointed comments to Texas Solicitor General Stone, “is to find the chink in the armor” of a 1908 case that permitted federal judges to temporarily stop the enforcement of state laws challenged as unconstitutional.

“And the fact that after all these many years, some geniuses came up with a way to evade the commands of that decision, as well as … the even broader principle that states are not to nullify federal constitutional rights, and to say, ‘Oh, we’ve never seen this before, so we can’t do anything about it,’ I guess I just don’t understand the argument.”

That final assertion may have been addressed to Kagan’s conservative colleagues who let the Texas law take effect two months ago.

Stone fought Kagan at every turn, saying that early abortions, prior to roughly six weeks, had continued in Texas. He defended the Texas Legislature’s effort to channel any litigation over the law known as Senate Bill 8 (SB 8) to state courts.

“This statute on its own terms specifically incorporates as a matter of state law the undue-burden defense as articulated by this court in Casey and subsequent cases,” Stone said, referring to the 1992 Supreme Court decision Planned Parenthood v. Casey, which reaffirmed Roe and prohibits government from putting an undue burden on a woman who wants to end a pregnancy before a fetus is viable, at 22 to 24 weeks.

Kagan offered an option for extracting the court from what she deemed the “procedural morass we’ve gotten ourselves into.” She suggested the high court allow a trial court judge to resume proceedings on the law (reversing an appellate court decision against the trial judge) and let the judge temporarily block enforcement of the law.

If the justices followed that route, she said, they could avoid ruling on the case brought by the Department of Justice against Texas, which she characterized as “very complicated for other reasons.”

That could appeal to Roberts, who dissented when the majority allowed the ban to go forward but on Monday was wary of the Department of Justice’s arguments. He told Prelogar that the law was “problematic,” but added that “the authority you assert to respond to it is as broad as can be … a limitless ill-defined authority.”

Alito also sharply challenged Prelogar. “A lot of your brief and all the other briefs that have been filed against Texas in both of these cases suggest that we should issue a rule that applied just to this case,” Alito said. “When we decide a case, the rule that we establish should apply to everybody who’s similarly situated.”

Prelogar and lawyer Marc Hearron, representing clinics challenging the Texas law, responded at various points that the unprecedented measure essentially required exceptional action.

Alito and Gorsuch drilled down on the clinics’ arguments that the sheer threat of the law, which would let people win at least $10,000 for successful suits against people who assist women in obtaining abortions, caused a “chilling effect” that would permit federal courts to intervene immediately.

They suggested the challengers were seeking special treatment for abortion-rights claims. Gorsuch referred to “defamation laws, gun control laws, rules during the pandemic about the exercise of religion that discourage and chill the exercise of constitutionally protected liberties. … And they can only be challenged after the fact,” not preenforcement.

Kavanaugh, too, was weighing other constitutional rights, but going in the opposite direction. He speculated that other states would copy Texas and “disfavor other constitutional rights,” such as those covering gun rights, the free exercise of religion, and free speech.

Texas’ lawyer Stone tried to reassure him that Congress could pass laws that allowed individuals trying to vindicate such rights immediately into federal court to block a state measure before enforcement.

“Well, for some of those examples, I think it would be quite difficult to get legislation through Congress,” Kavanaugh said, highlighting the consequences of the Texas scheme. “So we can assume that this will be across the board equally applicable … to all constitutional rights?”

Yes, Stone conceded.