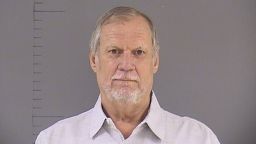

Terry Duane Turner, charged with the murder of a motorist who had parked in his driveway in Texas, “was defending himself and his property,” his attorney told CNN.

The family of Adil Dghoughi, the victim, said they are concerned Turner will use the state’s “stand your ground” law in his defense.

The Texas law says a person can use force as a means of self-defense if they reasonably believe the force is immediately necessary to protect them against another’s use or attempted use of force.

Here’s what you need to know about “stand your ground” laws.

What are these laws?

Generally, “stand your ground” laws allow people to respond to threats or force without fear of criminal prosecution in any place where a person has the right to be.

“They allow people to respond to threats of death, serious bodily injury, rape, and some other serious crimes with deadly force,” said Eugene Volokh, a law professor at the University of California, Los Angeles.

“Nearly all states allow the use of nondeadly force against a wide range of crimes (including theft, simple assault, etc.),” Volokh wrote in an email to CNN. “And nearly all states disallow the use of deadly force against minor crimes.”

Some self-defense laws state that a person under threat of physical injury has a “duty to retreat” before using deadly force. Volokh pointed out that there is a duty to retreat “only if they can retreat with complete safety.” If someone is pointing a gun at you, it is unlikely that is the case.

“Imagine you’re sitting in a bar and someone comes up to you and starts threatening you” with serious injury, Volokh said. In a “duty to retreat” state, you’d have to leave the bar. If that person then attacks you, “you’ve lost the right” to defend yourself with deadly force because you did not leave.

In a “stand your ground” state, someone facing an imminent threat can use lethal force right away if they are threatened with death or serious injury – without first trying to escape.

Even so, you “generally can’t use deadly force for self-defense in most states unless you reasonably believe that you’re facing the risk of death or serious bodily injury or some serious crime: rape, kidnapping or, in some states, robbery, burglary, or arson,” Volokh wrote on the subject.

States with ‘stand your ground’ laws

The number of states with a “stand your ground” law depends on the criteria used, Commissioner Michael Yaki said in a 2020 US Civil Rights Commission report on its investigation into Florida’s lawand similar laws and the race effects of those laws.

That’s because states may word and even enforce them differently.

The National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL) counted 25 as of May 26, 2020. At least three more have added “stand your ground” as laws since then: Ohio, Arkansas and North Dakota.

At least 10 of those states have laws that literally say that you can “stand your ground,” according to NCSL.

Florida was the first to pass a “stand your ground” law, in 2005, with 14 states adding their own in the following year, according to Yaki’s statement in the report.

Volokh said the debate goes back to basically the republic’s founding. He includes 37 states in his list of states that have “stand your ground” by statute or by judge-made common-law rules.

“The tide has been going in one way on this,” Volokh said, toward “stand your ground” and away from “duty to retreat.”

The Texas case

The confrontation between Turner, 65, and Dghoughi, 31, took place in the early hours of October 11 in Martinsdale, a small town about 35 miles south of Austin.

Turner told police he woke up to use the bathroom and saw an unknown vehicle parked in his driveway with its headlights off, according to an arrest affidavit obtained by CNN.

Turner said he got a handgun and ran outside to find the headlights of the vehicle turned on, according to the affidavit.

Turner told police that the car rapidly backed out of his driveway, he chased after it, and “struck the front driver’s side door window twice with his handgun” and fired the gun, striking the driver, the affidavit said.

According to court documents, Turner told a 911 operator after the shooting that “I just killed a guy,” adding that Dghoughi “started racing away and I ran after him. He pointed a gun at me, and I shot.”

Investigators didn’t find a gun in Dghoughi’s possession, according to the affidavit.

Dghoughi’s girlfriend told CNN he was driving from San Antonio to her home in Maxwell and probably got lost. She said she believes he pulled over to look up directions.

Turner’s attorney Larry Bloomquist told CNN his client is cooperating with police.

When asked how Dghoughi, who was sitting in a car, could pose a threat to Turner, Bloomquist said, “I’m not going to discuss specific facts of the case at this time.”

Mehdi Cherkaoui, an attorney representing the Dghoughi family, told CNN he could think of “1,001 things” Turner could have done differently to avoid the fatal shooting.

Cherkaoui said circumstances of the case make it look “pretty clear” that a claim of self-defense doesn’t apply in this case.

“I pray that when a grand jury hears this case, they will agree,” he said.

Why ‘stand your ground’ laws are controversial

Supporters of the laws, including the National Rifle Association, say they give people the right to protect themselves, no matter where they are.

The NRA has consistently trumpeted “stand your ground” laws as expanding the “constitutional right to self protection,” the Civil Rights Commission report said.

Critics say the laws encourage violence and allow for legal racial bias. In 2013, Sherrilyn Ifill, then president and director-counsel for the NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund, gave testimony in a hearing on “stand your ground” laws.

“Even those who do not consciously harbor negative associations between race and criminality are regularly infected by unconscious views that equate race with violence,” she wrote.

Racial stereotypes, she wrote, could cause people to misinterpret innocent behavior as something threatening or violent, and “stand your ground” laws could justify this violence.

The organization Brady: United Against Gun Violence calls them “shoot first” laws.

“At the crux of these ‘shoot first’ laws lies the belief that lethal force should be used on first instinct, instead of saving it as a last resort,” the organizationsays on its website. “This system relies on a ‘shoot first, ask questions later’ model that can quickly turn a simple misunderstanding into a permanent tragedy.”