Randy Gonzales grew up fishing with his father around the murky marshlands of St. Malo, a former village along the shore of Lake Borgne in Louisiana’s St. Bernard Parish.

What the fourth generation Filipino American did not know at the time was the deep, hidden history of his own heritage: More than a century ago, long before the Civil War, St. Malo was the first permanent Filipino settlement in the United States.

Anyone wanting to visit St. Malo now would need a tour guide and a boat to get there. Over the years, sea level rise, destructive storms, and environmental degradation have drastically changed the landscape of what was once a thriving fishing village.

“I grew up around some of the same spaces, but didn’t know the stories related to them,” Gonzales, an English professor at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette, and co-vice president of the Philippine-Louisiana Historical Society, told CNN. “So as I was learning about my own family’s story, it seemed imperative to want to tell the story of St. Malo — and ‘Manila Village’ — to better understand them.”

St. Malo’s early Filipino community prospered for decades. But the 1893 Chenière Caminada hurricane — a Category 4 on today’s scale — flattened the village, destroying huts and killing many in the community.

With their land flooded and farms gone, some survivors migrated to other parts of the state and the country. The rest moved a few miles away and later created their own “Manila Village” in the town of Jean Lafitte.

“The Filipino seamen in Louisiana were willing to live out in the marsh far away, so they could make a decent living, but it was a risk when the storms came through every 10 years or so, and then, the whole place was destroyed and they rebuilt,” Gonzales said. “And that’s the story of climate migration, where after a while, some of them had enough of the storms.”

Louisiana has always been on the frontlines of the climate crisis. As of 2016, the state had lost about 25% of the coastal land that existed in 1932, according to the US Geological Survey — which is roughly the size of Delaware. Experts say climate change, coastal erosion, sea level rise, and other human-caused environmental degradation have led to this point.

Now, as the Huffington Post’s Yasmin Tayag reported in June, the Filipino American community is faced with preserving its history as one of its most significant historical locations is lost to the sea.

Despite nearly two centuries of history, Filipino Americans in Louisiana say more people need to know the tale of the two villages: St. Malo and Manila Village in Jean Lafitte — and how climate change threatens their legacy.

Knowing a vanishing history

The history of Filipino American settlement in St. Malo is murky. There are no official documents to tell the story, and it has instead been passed down through generations in oral histories and old news articles written from “an Orientalist perspective,” Gonzales said.

Some say that the Filipino community in St. Malo goes back to as early as 1763 when both the Philippines and Louisiana were under Spanish rule. But Michael Salgarolo, a Filipino American archivist and historian at New York University, said the earliest known documentation of St. Malo being a Filipino settlement dates back to the early- to mid-19th century.

At the time, Filipino sailors were recruited for work on Western commercial ships through “coercion or some kind of debt bondage,” Salgarolo said, and later found themselves treated like indentured servants. He said some escaped when those ships landed at ports all over the world in places like Australia, South Africa and the United States.

Gonzales said in the late-1700s Filipinos likely escaped the Spanish ships and took refuge deep in the bayous of Louisiana, which was outside the range of census takers, law enforcement and the postal service. They built houses made out of sticks, he said, perched over the wetlands. Fishing became their livelihood in St. Malo, where they would trade with merchants in New Orleans.

“All throughout the 1800s, there are little pockets of Filipino sailors all over the world, and in a couple cases, particularly New Orleans, they form these kind of fishing settlements outside of outside of the port cities,” Salgarolo told CNN.

“For these Filipinos who ended up at St. Malo, part of what they wanted to do is they wanted to have a place of their own right, a place where they can control their labor and their lives,” he added.

The US Census Bureau estimates there were around 8,000 Filipinos in Louisiana as of 2019.

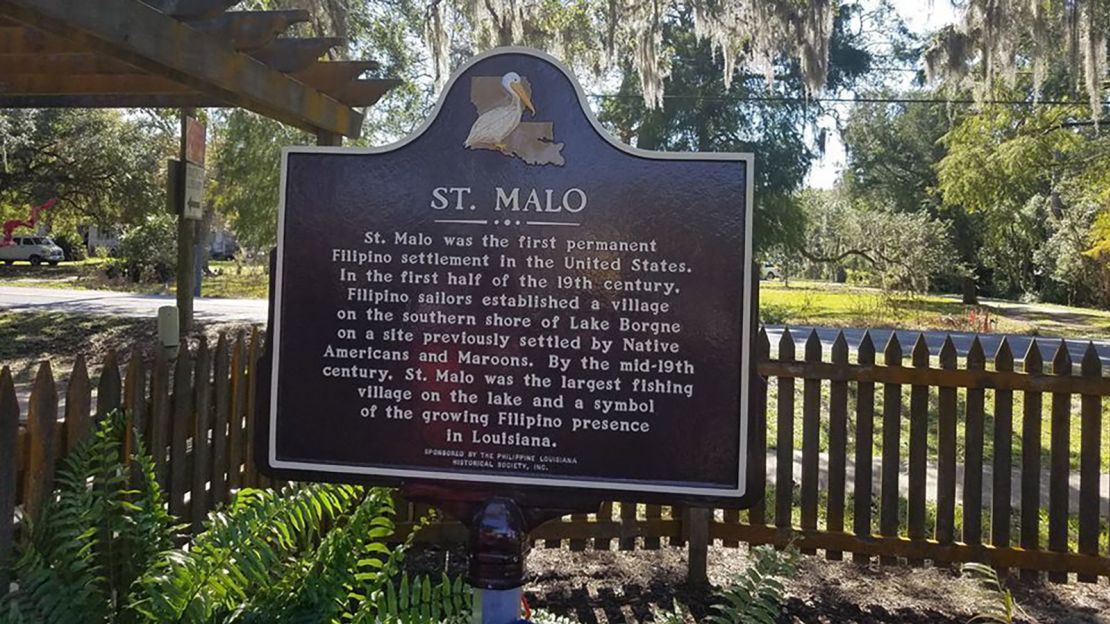

Filipino Americans in Louisiana have been fighting to tell their story for years. In 2016, the Philippine-Louisiana Historical Society won approval for a historical marker for Manila Village. In 2019, it successfully lobbied for a marker to commemorate St. Malo.

Gonzales said deciding where to put it was a challenge since no one ever goes to St. Malo, and they wanted it protected.

“We could have put it maybe further down the road in Shell Beach, which is the port you leave to get to St. Malo, but it’s a little less protected and harder to get to,” he said. “So it was the idea or thinking that well, if we want this story to be told, we need to put the marker in a place where people can access it.”

They ultimately decided to place the St. Malo marker by the Los Isleños Museum Complex, a Canary Islander heritage site in St. Bernard Parish and a good midway point between New Orleans and St. Malo. Gonzales said it “made sense to connect” both cultures since they not only live right next to each other, but they trace the same colonial roots.

Climate change threatening historical sites

As the climate crisis intensifies, Louisiana’s coast is being battered by sea level rise, more frequent hurricanes and erosion.

The amount of land lost in the region around St. Malo has varied over time, but researchers at the USGS estimate that from 1932 to 2016, it equates to an American football field lost every 34 minutes when the rate has been particularly high, and a field lost every 100 minutes when the rate has been low.

Denise Reed, coastal expert and professor of environmental sciences at the University of New Orleans, said sea level rise in southeast Louisiana is getting to a point where migration away from the coast will become more likely.

“If there are cultural sites, cultural relics or an archaeological site of historical interest, unless there are measures taken to specifically provide protection from erosion or to keep the water out, then they will succumb eventually,” she told CNN.

Even the town of Lafitte is at risk, Reed said: With the disappearance of barrier islands like Grand Terre and Grand Isle, which suffered the wrath of Hurricane Ida, the threat is expanding further inland.

“Coastal Louisianans already live on the edge, and climate change just makes it that much more precipitous for them,” she said. “The landscape is so much different from the way it was in the 18th and 19th century when a lot of migrant communities and Europeans came to settle.”

As an avid historian, Salgarolo wanted to visit St. Malo before it was swallowed by the seas. In 2019, around the same time of the unveiling of St. Malo’s historical marker, he and a few other people hired an eco-tour guide who ferried them on a small boat to the first Filipino settlement on a misty day. When they arrived, seagulls and pelicans flew over the wetlands. He described the wet and muddy journey as like a “pilgrimage.”

The imminent disappearance of St. Malo is a vivid testament to the risks the climate crisis poses to many of the world’s historical sites. For historians like Salgarolo and Gonzales, St. Malo is a significant place.

“It’s a beautiful space, but if you got out there you would say, ‘well, how could you live out here, perched up over the marsh, and if you do, what happens when a storm comes?’” Gonzales said. “That’s the danger of living out there.”

The window to learn more about this important part of Filipino American history in the bayous is slowly closing as sea levels rise, saltwater intrude, storms intensify, and ultimately, as the planet warms.

Filipino Americans living in coastal Louisiana, especially in Manila Village, which carried on the legacy of St. Malo, may have to migrate once more, even though its only been a few years since their historical markers went up.

But Gonzales said it’s the survival of the people who support that history that matter.

“The marker will be fine, but it’s the people who will continue to tell the stories about Filipinos in Louisiana that are impacted,” he said. “They’re very resilient people, but when you’re fighting for survival, the history becomes less important.”

“When people start migrating out, just like the Filipino fishermen who migrated away from St. Malo, when people from Lafitte start migrating out, the stories will be lost even further.”

Update: This story has been updated to give credit to the Huffington Post’s Yasmin Tayag, who covered St. Malo and its impending disappearance to sea level rise in June.