The raids started after midnight in Xinjiang.

Hundreds of police officers armed with rifles went house to house in Uyghur communities in the far western region of China, pulling people from their homes, handcuffing and hooding them, and threatening to shoot them if they resisted, a former Chinese police detective tells CNN.

“We took (them) all forcibly overnight,” he said. “If there were hundreds of people in one county in this area, then you had to arrest these hundreds of people.”

The ex-detective turned whistleblower asked to be identified only as Jiang, to protect his family members who remain in China.

In a three-hour interview with CNN, conducted in Europe where he is now in exile, Jiang revealed rare details on what he described as a systematic campaign of torture against ethnic Uyghurs in the region’s detention camp system, claims China has denied for years.

“Kick them, beat them (until they’re) bruised and swollen,” Jiang said, recalling how he and his colleagues used to interrogate detainees in police detention centers. “Until they kneel on the floor crying.”

During his time in Xinjiang, Jiang said every new detainee was beaten during the interrogation process – including men, women and children as young as 14.

The methods included shackling people to a metal or wooden “tiger chair” – chairs designed to immobilize suspects – hanging people from the ceiling, sexual violence, electrocutions, and waterboarding. Inmates were often forced to stay awake for days, and denied food and water, he said.

“Everyone uses different methods. Some even use a wrecking bar, or iron chains with locks,” Jiang said. “Police would step on the suspect’s face and tell him to confess.”

The suspects were accused of terror offenses, said Jiang, but he believes that “none” of the hundreds of prisoners he was involved in arresting had committed a crime. “They are ordinary people,” he said.

The torture in police detention centers only stopped when the suspects confessed, Jiang said. Then they were usually transferred to another facility, like a prison or an internment camp manned by prison guards.

In order to help verify his testimony, Jiang showed CNN his police uniform, official documents, photographs, videos, and identification from his time in China, most of which can’t be published to protect his identity. CNN has submitted detailed questions to the Chinese government about his accusations, so far without a response.

CNN cannot independently confirm Jiang’s claims, but multiple details of his recollections echo the experiences of two Uyghur victims CNN interviewed for this report. More than 50 former inmates of the camp system also provided testimony to Amnesty International for a 160-page report released in June, “‘Like We Were Enemies in a War’: China’s Mass Internment, Torture, and Persecution of Muslims in Xinjiang.”

The US State Department estimates that up to 2 million Uyghurs and other ethnic minorities have been detained in internment camps in Xinjiang since 2017. China says the camps are vocational, aimed at combating terrorism and separatism, and has repeatedly denied accusations of human rights abuses in the region.

“I want to reiterate that the so-called genocide in Xinjiang is nothing but a rumor backed by ulterior motives and an outright lie,” said Zhao Lijian, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman, during a news conference in June.

On Wednesday, officials from the Xinjiang government even introduced a man at a news conference they said was a former detainee, who denied there was torture in the camps, calling such allegations “utter lies.” It was unclear if he was speaking under duress.

‘Everyone needs to hit a target’

The first time Jiang was deployed to Xinjiang, he said he was eager to travel there to help defeat a terror threat he was told could threaten his country. After more than 10 years in the police force, he was also keen for a promotion.

He said his boss had asked him to take the post, telling him that “separatist forces want to split the motherland. We must kill them all.”

Jiang said he was deployed “three or four” times from his usual post in mainland China to work in several areas of Xinjiang during the height of China’s “Strike Hard” anti-terror campaign.

Launched in 2014, the “Strike Hard” campaign promoted a mass detention program of the region’s ethnic minorities, who could be sent to a prison or an internment camp for simply “wearing a veil,” growing “a long beard,” or having too many children.

Jiang showed CNN one document with an official directive issued by Beijing in 2015, calling on other provinces of China to join the fight against terrorism in the country “to convey the spirit of General Secretary Xi Jinping’s important instructions when listening to the report on counter-terrorism work.”

Jiang was told that 150,000 police assistants were recruited from provinces around mainland China under a scheme called “Aid Xinjiang,” a program that encouraged mainland provinces to provide help to areas of Xinjiang, including public security resources. The temporary postings were financially rewarding – Jiang said he received double his normal salary and other benefits during his deployment.

But quickly, Jiang became disillusioned with his new job – and the purpose of the crackdown.

“I was surprised when I went for the first time,” Jiang said. “There were security checks everywhere. Many restaurants and places are closed. Society was very intense.”

During the routine overnight operations, Jiang said they would be given lists of names of people to round up, as part of orders to meet official quotas on the numbers of Uyghurs to detain.

“It’s all planned, and it has a system,” Jiang said. “Everyone needs to hit a target.”

If anyone resisted arrest, the police officers would “hold the gun against his head and say do not move. If you move, you will be killed.”

He said teams of police officers would also search people’s houses and download the data from their computers and phones.

Another tactic was to use the area’s neighborhood committee to call the local population together for a meeting with the village chief, before detaining them en masse.

Describing the time as a “combat period,” Jiang said officials treated Xinjiang like a war zone, and police officers were told that Uyghurs were enemies of the state.

He said it was common knowledge among police officers that 900,000 Uyghurs and other ethnic minorities were detained in the region in a single year.

Jiang said if he had resisted the process, he would have been arrested, too.

‘Some are just psychopaths’

Inside the police detention centers, the main goal was to extract a confession from detainees, with sexual torture being one of the tactics, Jiang said.

“If you want people to confess, you use the electric baton with two sharp tips on top,” Jiang said. “We would tie two electrical wires on the tips and set the wires on their genitals while the person is tied up.”

He admitted he often had to play “bad cop” during interrogations but said he avoided the worst of the violence, unlike some of his colleagues.

“Some people see this as a job, some are just psychopaths,” he said.

One “very common measure” of torture and dehumanization was for guards to order prisoners to rape and abuse the new male inmates, Jiang said.

Abduweli Ayup, a 48-year-old Uyghur scholar from Xinjiang, said he was detained on August 19, 2013, when police picked him up at the Uyghur kindergarten he had opened to teach young children their native language. They then drove him to his nearby house, which he said was surrounded by police carrying rifles.

On his first night in a police detention center in the city of Kashgar, Ayup says he was gang-raped by more than a dozen Chinese inmates, who had been directed to do this by “three or four” prison guards who also witnessed the assault.

“The prison guards, they asked me to take off my underwear” before telling him to bend over, he said. “Don’t do this, I cried. Please don’t do this.”

He said he passed out during the attack and woke up surrounded by his own vomit and urine.

“I saw the flies, just like flying around me,” Ayup said. “I found that the flies are better than me. Because no one can torture them, and no one can rape them.”

“I saw that those guys (were) laughing at me, and (saying) he’s so weak,” he said. “I heard those words.” He says the humiliation continued the next day, when the prison guards asked him, “Did you have a good time?”

He said he was transferred from the police detention center to an internment camp, and was eventually released on November 20, 2014, after being forced to confess to a crime of “illegal fundraising.”

His time in detention came before the wider crackdown in the region, but it reflects some of the alleged tactics used to suppress the ethnic minority population which Uyghur people had complained about for years.

CNN is awaiting response from the Chinese government about Ayup’s testimony.

Now living in Norway, Ayup is still teaching and also writing Uyghur language books for children, to try to keep his culture alive. But he says the trauma of his torture will stay with him forever.

“It’s the scar in my heart,” he said. “I will never forget.”

‘They hung us up and beat us’

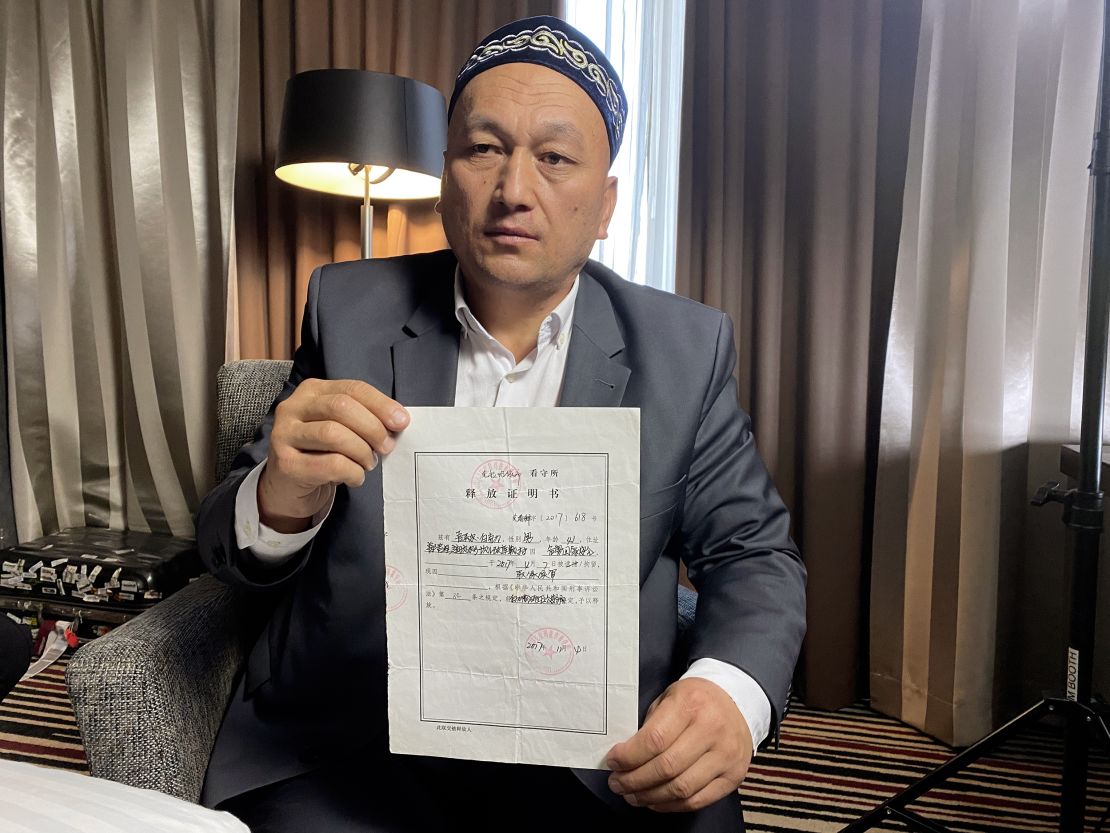

Omir Bekali, who now lives in the Netherlands, is also struggling with the long-term legacy of his experiences within the camp system.

“The agony and the suffering we had (in the camp) will never vanish, will never leave our mind,” Bekali, 45, told CNN.

Bekali was born in Xinjiang to a Uyghur mother and a Kazakh father, and he moved to Kazakhstan where he got citizenship in 2006. During a business trip to Xinjiang, he said he was detained on March 26, 2017, then a week later he was interrogated and tortured for four days and nights in the basement of a police station in Karamay City.

“They put me in a tiger chair,” Bekali said. “They hung us up and beat us on the thigh, on the hips with wooden torches, with iron whips.”

He said police tried to force him to confess to supporting terrorism, and he spent the following eight months in a series of internment camps.

“When they put the chains on my legs the first time, I understood immediately I am coming to hell,” Bekali said. He said heavy chains were attached to prisoners’ hands and feet, forcing them to stay bent over, even when they were sleeping.

He said he lost around half his body weight during his time there, saying he “looked like a skeleton” when he emerged.

“I survived from this psychological torture because I am a religious person,” Bekali said. “I would never have survived this without my faith. My faith for life, my passion for freedom kept me alive.”

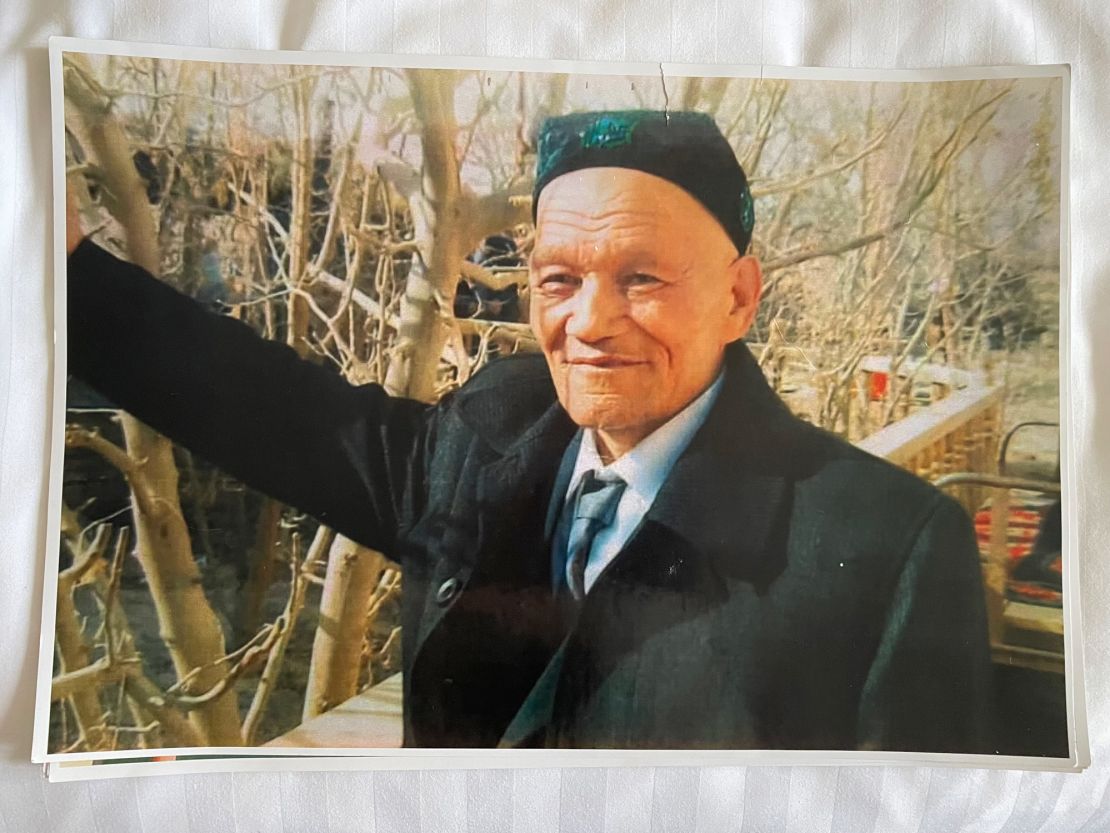

During his time in the camps, Bekali said two people that he knew died there. He also says his mother, sister and brother were interned in the camps, and he was told his father Bakri Ibrayim died while detained in Xinjiang on September 18, 2018.

Xinjiang government officials responded to CNN’s questions about Bekali during the Wednesday news conference, when they confirmed he had been detained for eight months on suspected terror offenses. But officials said his claims of torture and his family’s detention were “total rumors and slander.” His father died of liver cancer, they said, and his family is “currently leading a normal life.”

‘I am guilty’

From his new home in Europe, former detective Jiang struggles to sleep for more than a couple of hours at a time. The enduring suffering of those who went through the camp system plays on his mind; he feels like he’s close to a breakdown.

“I am now numb,” Jiang said. “I used to arrest so many people.”

Former inmate Ayup also struggles to sleep at night, as he suffers with nightmares of his time in detention, and is unable to escape the constant feeling he is being watched. But he said he still forgives the prison guards who tortured him.

“I don’t hate (them),” Ayup said. “Because all of them, they’re a victim of that system.”

“They sentence themselves there,” he added. “They are criminals; they are a part of this criminal system.”

Jiang said even before his time in Xinjiang, he had become “disappointed” with the Chinese Communist Party due to increasing levels of corruption.

“They were pretending to serve the people, but they were a bunch of people who wanted to achieve a dictatorship,” he said. In fleeing China and exposing his experience there, he said he wanted to “stand on the side of the people.”

Now, Jiang knows he can never return to China – “they’ll beat me half to death,” he said.

“I’d be arrested. There would be a lot of problems. Defection, treason, leaking government secrets, subversion. (I’d get) them all,” he said.

“The fact that I speak for Uyghurs (means I) could be charged for participating in a terrorist group. I could be charged for everything imaginable.”

When asked what he would do if he came face-to-face with one of his former victims, he said he would be “scared” and would “leave immediately.”

“I am guilty, and I’d hope that a situation like this won’t happen to them again,” Jiang said. “I’d hope for their forgiveness, but it’d be too difficult for people who suffered from torture like that.”

“How do I face these people?” he added. “Even if you’re just a soldier, you’re still responsible for what happened. You need to execute orders, but so many people did this thing together. We’re responsible for this.”