A terrorist attack didn’t stop Atifa Watanyar from teaching, but she worries the Taliban will.

Even before the militant group marched into Kabul, the English teacher felt intense uncertainty and heartache.

In early May, she was at the entrance of the Sayed Al-Shuhada school on the outskirts of the capital and saw an explosion in front of the main gate. As her students rushed past her, trying to escape onto the dusty yard below, a second and then a third bomb detonated, killing at least 85 people – many of them teenage girls.

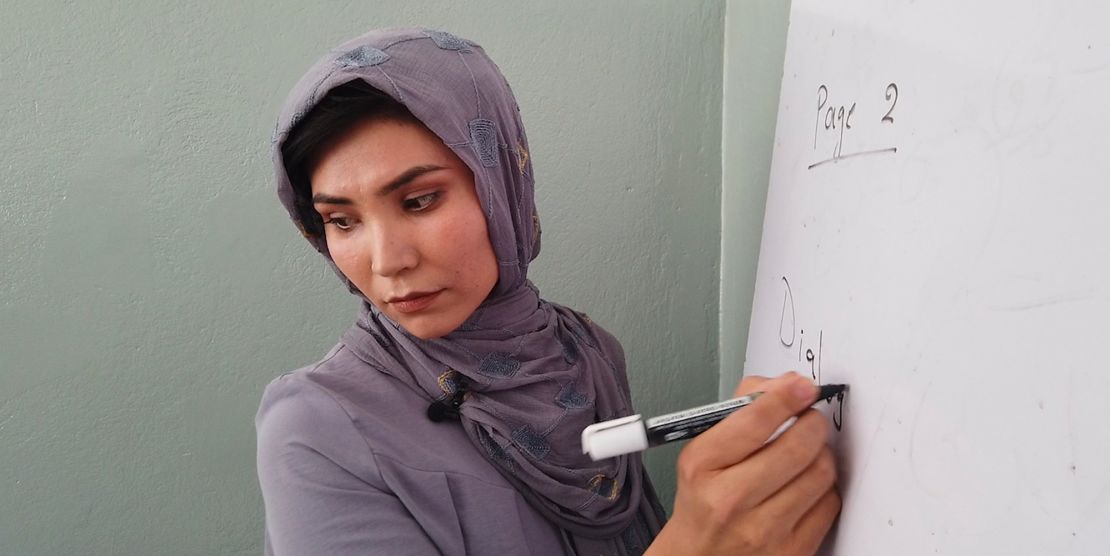

Just months later, Watanyar is standing at the very same entrance before her lesson begins. Young female students pour into the hallway, their voices echoing off a wall painted with a mural claiming “the future is brighter.”

“What should we say? Every day I see Taliban in the streets. I’m afraid. I fear from these people a lot,” she said.

In August, weeks after the school reopened, the Taliban swept to power and once again claimed Afghanistan as their Islamic Emirate.

A month later, the group effectively banned female students from secondary education, by ordering high schools to re-open only for boys. The group said it needed to set up a “secure transportation system,” before girls grades six through twelve could return. But the Taliban gave a similar excuse when it came to power in 1996. Female students never went back to class during its five-year rule.

No longer able to teach her older students, Watanyar now focuses on the younger girls, making sure inside her classroom at least, there is still room to dream.

“What should we do, what should we do? It’s just the thing that we can do for our children, for our daughters, for our girls,” she said.

Sanam Bahnia, 16, who was injured in the terror attack, was brave enough to return to class.

“One of my classmates, who was killed, was someone who really worked hard in her studies – when I heard that she was martyred, I felt that I must go back and study, for the peace of her soul, I must study and build my country, so that I can make their wishes and dreams come true,” she said.

But Bahnia’s ability to fulfill that pledge is in serious doubt. Now, prevented from attending school by the Taliban, she reads her textbook in the corner of her home. Her favorite subject is biology, but she says she no longer lets herself dream of becoming a dentist.

Her defiance in the face of multiple attacks on her future is taking its toll.

Her voice wavers as she begins to cry, saying: “The Taliban are the reason for my current state. My spirit is gone, my dreams are buried.”

The Taliban’s continued assault on women is visible across this city. Militants have in some instances ordered women to leave their workplaces, and when a group of women protested the announcement of the all-male government in Kabul, Taliban fighters beat them with whips and sticks.

On the streets of the Khair Khana neighborhood, in northwest Kabul, the consequences of a recent women’s protest remain. At almost every beauty salon, images of women’s faces have been defaced. Some were quickly spray painted black, others whitewashed completely.

Inside one of the salons, the women are too afraid to give their names. They say that the Taliban drove away the protesters, before telling them to remove the images of women, put on burqas and stay home.

Still, despite remarkable odds, Kabul’s female activists continue to organize and demonstrate.

Last Thursday, just a handful of female protestors were met by an entire Taliban unit. Right as the women held up signs declaring, “Education is human identity” and “Do not burn our books, do not close our schools,” military pickup trucks descended on their protest corner.

Taliban fighters ripped the signs out of their hands, as a mounted machine gun fired off a warning burst that sent spectators and journalists running.

The Taliban’s head of intelligence services in Kabul, Mawlavi Nasratullah, said that the women didn’t have permission to protest.

When asked by CNN’s Clarissa Ward why a small group of women asking for their rights to be educated threatened him so much, Nasratullah responded: “I respect women, I respect women’s rights. If I didn’t support women’s rights, you wouldn’t be standing here.”

But the violence repeated at other protests tells a different story.

“When you leave your house for a struggle, you consider everything,” protest leader Sahar Sahil Nabizada said, adding that she’s been threatened repeatedly but refuses to leave the country or stop organizing.

“It’s possible that I die, it’s possible I get wounded, and it’s also possible I return home alive. However, if I, or two or three other women die or get injured, basically we accept risks in order to pave way for the generations to come, at least they will be proud of us,” Nabizada said.

Most acts of daily defiance are smaller and less public, but just as important, activists say. More and more women are returning to Kabul’s public spaces after staying inside during the initial first few uncertain weeks of Taliban rule.

Arzo Khaliqyar is one of those women who went back to work. The mother of five says she was forced to become a taxi driver when her husband was murdered a year ago. She says he left behind his white Toyota Corolla, a common car in Kabul, but little else.

But in the weeks since the Taliban came to power, driving has become increasingly difficult and she says she is routinely threatened. She’s adapted by sticking to neighborhoods she knows and picking up mostly women and families.

“I know [the risks] very clearly but I have no other option,” she said. “I have no other way. In some places where I see Taliban checkpoints, I will change my route. But I’ve accepted this risk for the sake of my children.”