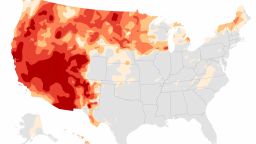

Global scientists reported in August that due to the climate crisis, droughts that may have occurred only once every decade or so now happen 70% more frequently. The increase is particularly apparent in the Western US, which is currently in the the throes of a historic, multiyear drought that has exacerbated wildfire behavior, drained reservoirs and triggered water shortages.

More than 92% of the West is in drought this week – a proportion that has hovered at or above 90% since June – with six states entirely in drought conditions, according to the US Drought Monitor. On the Colorado River, Lake Mead and Lake Powell – two of the country’s largest reservoirs – are draining at alarming rates, threatening the West’s water supply and hydropower generation in coming years.

Though summer rainfall brought some relief to the Southwest, the unrelenting drought there is about to get worse with La Niña, according to David DeWitt, director at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Climate Prediction Center.

“As we move into fall, from October on, the Southwest US, based on all the best information that we have, they’re going to see persistent intensification and development of drought,” DeWitt told CNN. “There’s, at this point, not any indication that they’ll see drought relief.”

La Niña is a natural phenomenon marked by cooler-than-average sea surface temperatures across the central and eastern Pacific Ocean near the equator, which causes shifts in weather across the globe. In the Southwest, La Niña typically causes the jet stream – upper-level winds that carry storms around the globe – to shift northward. That means less rainfall for a region that desperately needs it.

La Niña conditions have emerged in the tropical Pacific Ocean over the past month, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration said Thursday. With that and warming temperatures, DeWitt said the Southwest will see enhanced evaporation that will intensify drought in certain places.

“The net water balance going forward, from this point as the summer monsoon ends, is that we’re going to see conditions continue to dry out,” DeWitt said. “Places that have droughts will kind of persist or intensify, and places that don’t have drought right now because it was recently ameliorated, we expect drought is going to redevelop.”

NOAA published a report this week on the Southwest’s historic drought, addressing a key question of when it might end. The answer, according to the report, is that the current drought could last into 2022 – or potentially longer.

“More widely, my guess is that for much of the West, the current extent and magnitude of this drought is locked in until at least mid-2022,” Justin Mankin, assistant professor of geography at Dartmouth College and co-lead of NOAA’s Drought Task Force, told CNN.

The NOAA report concluded that climate change-fueled drought will continue to worsen and impose greater risks on the livelihoods and well-being of over 60 million people living in the Southwest, as well as the larger communities that rely on their goods and services.

“This has big implications for drought mitigation measures for different water districts, many of which are working hard not only to manage the impacts of this drought, but to invest in longer-term adaptive measures to be resilient to more droughts like this in the future,” Mankin said. “Given scant resources to do both, these water districts need our support.”

The nation’s largest reservoirs, Lake Powell and Lake Mead, are at record-low levels. Both are fed by the drought-ravaged Colorado River watershed, and supply drinking water to 40 million people and irrigation to rural farms, ranches and native communities.

The Bureau of Reclamation in August declared a water shortage on the Colorado River for the first time, triggering mandatory water consumption cuts for states in the Southwest beginning in 2022.

Projections released in September show a 66% chance that water levels at Lake Mead could drop to a level that would trigger even deeper cuts, potentially affecting millions of people in California, Arizona, Nevada and Mexico.

The agency also projected a 3% chance that Lake Powell next year could drop below the minimum level needed for the lake’s Glen Canyon Dam to generate hydroelectricity. In 2023, the chance of a shutdown grows to 34%.

Drought and blistering heat has fueled major wildfires in the West this summer. According to Philip Higuera, fire ecology professor at the University of Montana, warming temperatures caused the record-low level of rain and humidity that dried out trees and vegetation, which in turn ignited more wildfires.

“You can have the same amount of vegetation in a forest, but if it’s wet, it’s not available to burn,” Higuera previously told CNN. “These regions across the West that have record dry fuels, that makes more vegetation available to burn – so basically, more of the forest is participating in these fires.”

Oregon’s Bootleg Fire, which started in July, became the second largest wildfire in the country this year; meanwhile, California battled the Dixie Fire – the largest in the US this year and second-largest in state history. Currently, firefighters are battling the lightning-sparked KNP Complex and Windy fires, which are threatening Sequoia National Park and national forest.

According to Mankin, the longer-term fate of the Western drought remains bleak. What’s needed now, he said, is several years of rain and mountain snow to replenish the draining reservoirs and rivers.

That becomes more unlikely as the climate crisis worsens. Experts say the West will only continue to see more droughts like the present one in the years to come — and only rapid, immediate cuts to fossil fuels can halt this harsh trend.

“Global warming is making the atmosphere over the West warmer and thirstier, such that even the rain and snow that was once normal may be too little to quench it,” Mankin said. “The only way to stop the kind of atmospheric demand increases that have made this drought so impactful, is to stop combusting fossil fuels.”