Angela Merkel has been written off many times in her career – by the politician’s rivals, her own party members and, yes, the press.

It’s difficult to imagine today, as Germany’s widely respected Chancellor prepares to step down after more than 15 years in the top job, but in the early stages of her career Merkel was regularly belittled and looked down on – even by those who were supposedly on her side.

The protégé of then-Chancellor Helmut Kohl, Merkel was known by him as “mein Maedel” – “my girl.”

“She always was underestimated by her enemies and by other politicians, and when they realized that a woman from the east is able to play this power game, it was too late,” Ralph Bollmann, author of the authoritative Merkel biography “Angela Merkel: The Chancellor and Her Time,” told CNN.

The media only added to this sense that Merkel was not a serious political contender.

At one of her earliest media appearances as the new leader of the center-right Christian Democratic Union (CDU) in Berlin in 2001, Merkel appeared out of her depth.

Uneasy in front of the bright lights and cameras of the press pack, she seemed not to know where to look or what to do with her hands, and gave flat, boring answers to reporters’ questions. Chatting afterwards, many of the (mostly male) journalists present agreed: This woman would never be chancellor.

But what did they know? Merkel went on to secure four terms in office, making her one of the longest-serving chancellors in German history – only Kohl, the mentor she eventually turned her back on, has served longer in the modern era.

Two decades on, she has cemented her position as an elder stateswoman, having led her nation – indeed some would argue Europe as a whole – through a series of potentially devastating crises.

Named the most powerful woman in the world several times over, Merkel also played a crucial role on the international stage, helping to manage the global financial crisis, the refugee crisis, and the war in Ukraine.

As Germany prepares to go to the polls this weekend to elect a new government, and by extension her successor, it is not clear whether any of those lining up to replace her – Armin Laschet of Merkel’s own CDU, the center-left Socialist Party (SPD)’s Olaf Scholz, or the Greens’ Annalena Baerbock – will be able to fill her shoes.

Bollmann says the world will sorely miss Merkel’s steady leadership: “I think there is one common thing in Germany and abroad: She is seen as a guarantor of stability. In future times many people will look back at this time as a time – perhaps the last time – of stability.”

‘Don’t fool yourself’

Merkel, 67, grew up under Communism in East Germany, and trained as a scientist, earning a doctorate in quantum chemistry before making a move into politics following the fall of the Berlin Wall. She won a seat in the Bundestag, Germany’s parliament, in the first election after reunification.

In the years that followed, Merkel would not only become the first female Chancellor of Germany but would also change the country’s politics for good.

Yet when the CDU won Germany’s elections in 2005 – by just 1% – it was widely seen as having happened despite Merkel’s perceived weaknesses, not because of her.

Appearing on TV talk show “The Elephant Round,” after the nail-bitingly close 2005 vote, the incumbent Chancellor Gerhard Schroeder appeared dismissive of Merkel, laughing off the notion that she would be able to form a governing coalition.

“She will not manage to form a coalition with my Social Democratic Party,” he said. “Don’t fool yourself.”

Merkel held her tongue, but went on to do just that, patiently biding her time before working to form a so-called “grand coalition” between the two largest parties – the CDU and the SPD – and, in doing so, ending Schroeder’s political career. The imperturbable, unemotional Merkel had triumphed.

“There are many things she learnt from her youth … in the GDR, in Communism, because she had to hide her real opinions, not saying something … she’s a very quiet person, she’s patient,” Merkel biographer Bollmann told CNN.

The early years of Merkel’s chancellorship were largely uneventful. Germany’s economy slowly gained steam after years of stagnation. But in 2008, when investment banking company Lehman Brothers collapsed and the world seemed headed for an economic abyss, Germans feared their export-dependent nation could go under.

That’s when Merkel took charge, becoming the country’s crisis manager.

On October 5, 2008, she told Germans: “Your savings are secure, the federal government guarantees that.” Her calm, reassuring words helped to prevent a run on the banks and marked the start of a period of confidence in the face of adversity for Germany, led by Merkel.

Her government started a short-term labor program, known as “Kurzarbeit,” which helped companies keep their employee on staff by making them work shorter hours, while the government supplemented their incomes.

The program cost around 6 billion euros, according to the Federal Employment Agency, but it helped Germany avoid mass unemployment and ensured that German companies were at an advantage once the global economy picked up, since they had retained their skilled workforces.

By the time the Greek debt crisis hit in 2012, Germans had faith in their chancellor, trusting that she could handle the adversity.

Merkel took charge, creating giant funds to save not just Greece’s economy but those of other debt-ridden Eurozone nations as well. Though Greece and other countries criticized what they saw as the draconian terms of their bailouts, Merkel likely saved the single currency.

“Europe will fail if the euro fails. Europe wins if the euro wins,” Merkel told the German Bundestag in 2012.

“She has led Germany, Europe and, in parts, the rest of the world through an era of crises – big crises – which we never thought could happen in a Western democracy,” says Bollmann.

But while Merkel is seen as a bold and accomplished crisis manager, critics say she risked alienating the conservative voter base of her own party, the CDU, by taking left-of-center positions on key topics including nuclear energy, foreign policy and immigration.

Merkel’s government had initially halted Germany’s planned exit from nuclear energy, but she reversed that decision in the wake of the Fukushima disaster in 2011. The move was popular with those on the left, but not necessarily with CDU supporters.

“The phenomenon of Angela Merkel is basically leading from behind,” said Julian Reichelt, managing editor of Germany’s largest daily tabloid newspaper, the right-leaning BILD. “You see where people are going and you follow the masses, you don’t lead the masses. She was brilliant at doing that.”

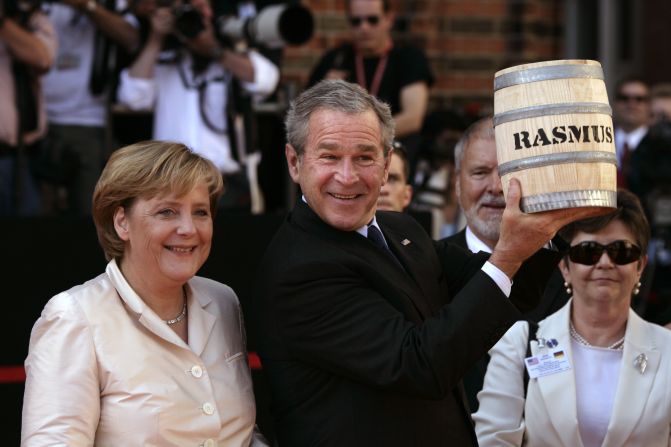

Angela Merkel's life in pictures

The same was often true in foreign policy, which saw Germany’s role shrink, compared to the Schroeder years.

“Germany certainly punches below its weight when it comes to foreign policy,” Reichelt told CNN. “Angela Merkel tried to ignore all major conflicts and problems all over the world as good as she could. She was one of the champions of ignoring all the problems that were so obvious in Afghanistan and which would obviously hit us after the withdrawal.”

Arguably, Merkel’s highest-profile moment of international leadership came in the summer of 2015 when hundreds of thousands of refugees, mostly displaced by the civil war in Syria, made their way to Europe.

While many of her fellow leaders across the European Union argued in favour of trying to stop the masses from entering thebloc, Merkel believed that the moment called for a huge humanitarian response.

“Germany is a strong country. We have achieved so much – we can do it!” Merkel famously said at a press conference in 2015, opening her country’s doors to the refugees. “We will manage this, and if something stands in the way, it must be overcome.”

Germany eventually welcomed an estimated 1.2 million refugees over the next year and a half.

Hajo Funke, a professor at Berlin’s Freie University, believes opening Germany and Europe up to the influx of people in need was one of the greatest humanitarian acts in German history. “This was a golden hour of the post-World War II democracy. This is the legacy: To be non-nationalist,” Funke told CNN.

In the wake of Merkel’s call to action, many Germans welcomed the asylum seekers with food and clothes; some opened their homes to those who had made the arduous journey, or helped them find work.

But the magic of the moment eventually wore off. Integrating the new arrivals was a tricky task some critics say was handled poorly.

Her handling of the refugee crisis put a dent in Merkel’s popularity at home and helped fuel the rise of far-right political forces including the Alternative for Germany (AfD). The AfD became the first far-right group elected to the Bundestag since 1961. It came third in the 2017 election, with 12.6% of the vote.

While Merkel did win another term as chancellor, poor showings for her party at local elections convinced her it was time for change; in 2018 she announced that she would hand over the leadership of the CDU, and that she would not seek re-election in 2021.

But a new crisis soon came knocking.

In early 2020, when the Covid-19 pandemic hit, Merkel was one of the first world leaders to acknowledge the scale of the health threat posed by coronavirus.

“Since German unification, no, since the Second World War there has not been a challenge to our nation that required us to act in solidarity with one another so much,” she said.

Under her leadership, Germany quickly introduced a strict lockdown, reinstated the “Kurzarbeit” program to protect the economy, and helped launch the search for a vaccine.

Merkel’s handling of the pandemic saw her popularity spike, as Germans once again learned to appreciate the dogged resolve of their often-underestimated leader.

Some are left doubting whether those lining up to take her place as chancellor will match up to their predecessor.

“The question is: Who’s going to replace (Merkel), and will that person have the same charisma and ability that she did?” Ben Schreer, from the International Institute for Strategic Studies’ (IISS) wondered in an interview with CNN earlier this week. “Allies are skeptical, and Germans as well are quite cautious in that regard.”

Laschet, Scholz and Baerbock can perhaps take some comfort from the fact that pundits and politicians alike once doubted Merkel’s abilities too.

As the politician who arrived on the scene as an inexperienced “Maedchen” prepares to leave the world stage, Germany’s voters are left wondering who will fill the void left by the woman they came to know affectionately as “Mutti”: the mother of the nation.